FIVE OR SIX YEARS AGO I went to look at a landscape exhibition on Broughton at a gallery that no longer exists. The landscapes didn’t interest me, but in the back room I discovered a couple of paintings by Savannah painter, Luther Vann, that impressed me. Apart from a small exhibition of his works at the Hurn Museum two years ago, this present exhibition at the Jepson is the only other opportunity I have had to see his work.

What immediately impresses me in Vann’s work is that it is what I would describe as an excellent example of “real” painting, and I can best tell you what I mean by “real” painting by stating what it is not: it is not collage or mixed media; it is not digital or assemblage; it is not projected or traced; it is not conceptual or design. It is, in fact, pre-Pop Art, and belongs to the Modern, rather than to the Post-modern period.

In “real” painting, the artist confronts the blank canvas with apprehension, armed only with paint and brushes, an idea that cannot be expressed in words, and perhaps just a few sketches. The painting is realized in the process of its creation, and the end result can often surprise the painter, himself.

As Vann says in his statement, “It has been my personal experience that as I allow the painting to speak, I become lost. It is a delicious and at times a frightening experience....”

“Tales of a Shaman” is a large, vertical canvas with figures drawn in contour lines of intense pure colors on a black gesso background. Two large figures occupy the lower section of the painting, one sitting and one standing. Above them, in the center and on a smaller scale, a number of figures are sitting at tables as if in a restaurant and above these, we can see some buildings of the city.

These three variant scales disturb the traditional single point of view of Western figurative painting, and suggest several different readings. One is the mystical interpretation which seems popular - since the figures occupy different or parallel worlds of space and time, we are viewing a dialogue between the living and the dead.

Another reading might give us a depiction of space as in a traditional Chinese landscape: the near distance, the middle distance, and the far distance, all seen as if on top of one another.

Then, there is a third interpretation in which there is no illusion of space, but the figures are drawn haphazardly on the canvas, overlapping and on different scales, as they would appear on a sketchbook page.

Sometimes, as with this painting, the drawing with paint remains an outline, often fluid but then becoming more erratic, like the game of connecting dots or diagrams of the constellations. In other paintings, this outline is filled in with a frenetic hatching of colored lines. The paintings have the quality of colored drawings, which can be explained by Vann’s usual choice of using chopsticks to apply his marks, instead of brushes

And sometimes, it is as if Vann just up and changed his mind or direction half way through. In “All the Things We Are,” we see a woman with a child sitting on the grass, two dogs lying on the grass, a small boy walking towards us, and the back leg of a cropped figure walking away. These are all viewed as if the artist were sitting on the grass drawing the figures; they are on the small level.

But there is a peculiar vertical strip of gesso with a line drawing at the left edge of the painting, that if I turn my head at the correct angle, reads like the tops of heads of figures. I think this painting started life as a vertical canvas with a colored line drawing as in the “Tales of a Shaman,” and then, for some reason was abandoned. Perhaps Vann was interrupted and couldn’t return to it for a while, and when he did, he turned the canvas horizontally and began a new work, leaving this hint of another road not taken.

Vann seems to work from a combination of observational drawing and memory. For instance, three different sketches of the same woman wearing a red hat and a belt purse appear in three small chopstick paintings.

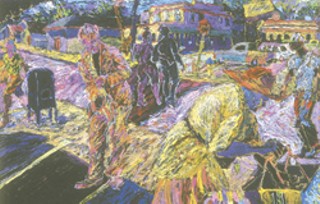

In one, “Habersham and 41st Street,” she is one incident in the narrative, one character among others - a saxophone player and various youths in the background - as she moves along the sidewalk holding onto what seems like the top of a shopping cart.

In “Yard Sale, Lady in a Red Hat,” she completely dominates the picture plane as she searches through objects for sale. And here perhaps is the difference between the small and large works.

I believe Vann makes sketches from life and the small paintings expand on one sketch, from one point of view, where the large works incorporate multiple sketches and have many points of view. It is reminiscent of the films of Kieslowski, the great Polish filmmaker (“Red”, “White”, “Blue”), who features the narrative of certain protagonists in a single film of a series, while allowing them to move into the other films as background characters, tying everything together in one larger and more complex world.

What I call “real” painting is very hard to do these days. It requires a commitment to the language of painting, a subject matter that the artist loves and never tires of, and the use of techniques that would have been discovered through experimentation and accident, not those selected from the recipe book of pre-digested techniques taught in school.

But all these things require more time, patience and serious purpose than most artists in these fast paced times can summon up. Vann succeeds because he has a subject – the life observed in houses, on the streets and in the parks of his city - and a technique he has made his own: his use of saturated, unmixed colors on a black ground which creates a kind of luminosity.

If we add to that his obvious trust in the process of painting to produce something of quality for his thoughtful efforts, what we have is “real” painting.