Maybe you glimpsed their festooned glory on your Instagram feed, or perhaps you got to gawk at them in person as they toured the town on the back of a flatbed truck. The Yarn Children of Collaboration bombarded the streets and social media last week, and hopefully, Savannah will never be the same.

First conceived to help fulfill the mission of last Saturday's A-Town Get Down Festival, the splashy mobile sculptures were assembled by the kids of the Loop It Up Savannah art program at the West Broad YMCA—a fine, fun example of how the sum of many creative efforts can add up to a single piece of art. The back story, however, has more layers than a Kardashian wedding cake.

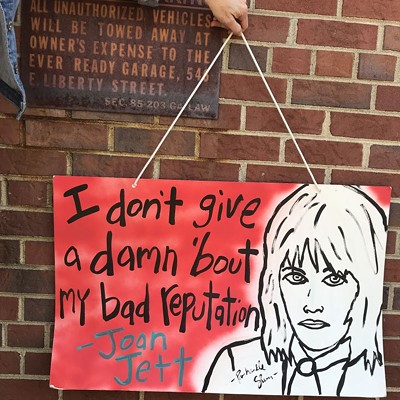

A few months ago, artist and A-Town art coordinator Jose Ray approached Loop It Up director Molly Lieberman and myself about a yarnbomb for the event. A "yarnbomb" is what happens when knitters get nutty and cover an everyday structure—a mailbox, a stop sign, the neighbor's dog—with fibers, instantly transforming the mundane into art, or at least something a little less ordinary. I got awfully excited, 'cause doing stuff that will make people laugh, stare and/or point is kinda my hobby. (A group of us yarnbombed Green Truck Pub in December, and the dashboard of my minivan is kind of a situation.)

A yarnbomb also serves to bring together makers and viewers in unexpected ways, making it a perfect opportunity to thread together A-Town, its connections with SCAD, the local art community and the families of the Y—as well as honor A-Town's inspiration, Alex Townsend, a vibrant young soul who died in a car accident in February 2010.

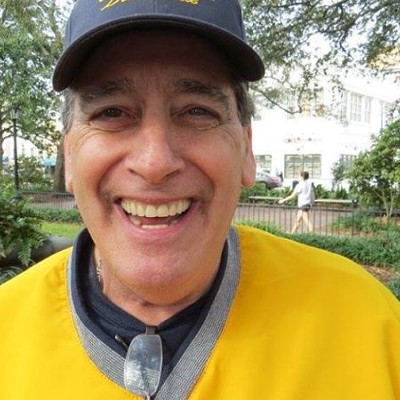

Several brainstorming sessions ensued. Our intrepid triad realized this project would need to travel, and building a mobile structure from scratch would require time and power tools, both in short supply. I went to ask sculptor Jerome Meadows if he had any suitable spare items lying around his studio behind Indigo Sky Community Gallery.

Always down for any kind of artistic mischief, Jerome showed me a massive propeller blade reclaimed from an industrial site. Too unwieldly.

He put his hand on a block of granite. Oy, too heavy.

He thought a minute and disappeared into the back of his cavernous work space, then toddled out a three-and-a-half foot human form made of twisted chicken wire and stuffed with wads of paper. He introduced it as one of three armatures used for a public art project ages ago, and we were welcome to them.

"They're perfect," I exclaimed, clasping my hands as if he'd presented a trio of magical creatures.

There was definitely something spellbinding about the Children. As we loaded them gently into the minivan, taking care to avoid any sharp pokes, I wondered briefly if they needed seatbelts.

The Loop It Up kids spent many afternoons weaving ribbons and yarn on cardboard looms to dress them, giving the girl form a purse and naming her "Diva." Purled squares made by the elders of the Hudson Hill Golden Age Center appeared.

As they became bedecked in every color and fiber imaginable, including violet swaths of donated fabric called "Savannah Plaid," the Children became softer and more alive, as if they might dance right off their foundations.

We found ourselves patting their heads and cooing to them, and they enchanted everyone who walked past, their vibrant fringes giving off the effect of three friendly shamans.

Diva and the boys looked wildly regal as Jose, Connect's Sinjin Hilaski and I strapped them to a flatbed truck for a tour of the city, with a plan to snap photos for a social media blitz and introduce our charges to the age-old Savannah pastime of "see and be seen."

Jose drove us through Frazier Homes, the public housing community where many of the Y kids live, past City Hall and around the squares. We cruised Broughton, checked out the Telfair, stopped for coffee at the Sentient Bean.

The Children seemed to take in the uproar they caused everywhere we went with a wise, quiet humor. They didn't complain at all as they jostled on our shoulders as we carried them to the Forsyth Fountain and crowded into the elevator at Drayton Tower.

Frankly, they were much better behaved than a lot of children I know. Come to think of it, most adults, too.

Whose children are they, anyway?

Because of Jerome's low-key modesty, I didn't pick up on the marvelous relevance of the chickenwire children until I did a bit of research on the actual sculptures they spawned. It turns out our colorful little beings served as the molds for the bronze figures in Yamacraw Square, the $300K public art project that brought Jerome—a public art master known all over the world for his curated community gathering spaces—to Savannah from Washington, D.C. in the first place.

Back in 1992, a Leadership Savannah class voted to do something that could connect Savannah's bustling tourist district with the public housing site Yamacraw Village. The site of Gen. Oglethorpe's first meeting with Chief Tomochichi, it has been a neighborhood of mostly black, mostly poor folks for the past 100 years, its historic significance obscured by a dangerous reputation. It's just steps away from downtown's busiest hotels and restaurants, yet it might as well be a mile.

Meadows' vision was to transform the patch of land across the street from the historic First Bryan Baptist Church into a space that was at once enjoyable and educational. Paths lead in through the apartments and from Bay Street past a series of walls designated for historic lore and stone benches meant for communing. The centerpiece is a fountain upon which three beautifully-rendered bronze figures—the solid counterparts to our yarn children—dance and play, showing their joy to the world.

"It's the only spot where Savannah's African-American, Native American and mainstream histories collide," he explained when I finally figured out that our yarn children were, in a way, reincarnating his original idea of collating different niches of our larger community.

Due to bureaucractic clustercussery and ballooning budgets, the Yamacraw Square Public Art Park wasn't dedicated until 2007—almost 15 years after its conception. Corners had to be cut on construction, and the intended bronze plaques were replaced with cheaper tintypes. Vandals defaced these almost immediately, and in spite of many dedicated community volunteers, Yamacraw Square didn't exactly "take" as a unifying gathering place.

These days, the bronze children dance in an empty fountain, broken glass at their foundations. The city still cuts the grass and empties the trashcans, but maintenance isn't the same as upkeep, and there's no public money to fix the park.

"This is a complicated case," sighs MPC Urban Planning Director Ellen Harris, who oversees the Site and Monument Commission. "The city says the Housing Authority is responsible for it, the Housing Authority says the city is responsible. It's been a stalemate for years."

Harris has received a $100K budget proposal to restore the park, but not a strategy on how those funds would be raised.

"Even if the city maintains them, monuments are generally paid for with private money," explains Harris, adding that newer projects, such as the WWII Memorial on River Street, are required to have an escrow account from which restoration funds can be drawn in perpetuity.

Though nearby residents were engaged in the original design process and a committee of progressive citizens helped raise the cash, the momentum has dissipated. Project leaders already spent a decade and half collating the original capital, which included $70K of SPLOST money, and no one can blame them for feeling a little burned out. Still, the idea that Yamacraw Square should be treated differently than any other city property doesn't sit right.

"If something happened in Pulaski Square, somebody would be there to do something about it," points out Earline Davis, Executive Director of the Housing Authority of Savannah. "Why are some public spaces treated like stepchildren? They're all a part of the system."

Davis gives a rueful laugh when it's suggested that her agency put up the cash to fix the art park.

"Believe me, if the money was there, we'd do it," she says. "There is value in art, and if you don't have access to it, you can't be expected to grow and know about the world."

But with 12,500 residents in eight public housing neighborhoods to oversee, Davis' priorities are just keeping the lights on. That may change as HUD public housing projects transition into Section 8 properties, giving local agencies ownership over the apartment buildings. In the meantime, Yamacraw Square remains neglected by the city at large.

"If you don't maintain the relationships, it doesn't really work," says Davis. "It was well-intentioned, but they didn't give it enough long term thought."

'Never just black & white'

It would be easy to view the plight of Yamacraw Square with the same lens through which many view Savannah, that the effort has been made and there isn't anything left to be done. That the chasms between the haves and have nots, between our black and white citizens, between those deemed deserving of public art and those who should just be grateful to have a place to live at all are just too large to bridge, even if the physical distance isn't so far at all.

But collaboration makes strange bedfellows. Molly has had tremendous participation in the Loop It Up program, and both the Yarn Children and their forgotten bronze counterparts have already brought together people of all ages and colors. The marvelous coincidence that allowed us to bring these figures out of their neighborhood onto to the streets serves to remind that life in Savannah is far more vibrant and complex than simple dichotomies. But it takes a willingness to ask the same questions and visit the same issues over and over again, keeping faith that patience and passion will yield progress—even if it takes decades.

I visited Yamacraw Square on several occasions, with and without the Yarn Children. The first few times, the park was clean but desolate, the surrounding buildings dotted with boarded up windows, a line of drying laundry nearby the only evidence of human presence.

The scene summed up the story I'd been told about this neighborhood, but something kept calling me back. Intern Sinjin and I popped over again one late afternoon last week, just as the schoolbuses were pulling up. Soon the square and street were flooded with uniform-clad tots bouncing balls and whipping past on scooters.

We struck up a conversation with Talethia Dortch, who lives next to the park, and she assured us that even its derelict state, it still gets used for barbecues on summer evenings and occasionally, a wedding.

"It would be nice to have the fountain working again," she said amiably, keeping an eye on her 8 year-old daughter, Marinsaja, as she pushed a toy baby carriage along the sidewalk. "The kids really like that."

Talethia is working towards her nursing certification at Savannah Tech, and she and Marinsaja often enjoy Savannah's other public spaces. She grew up in Yamacraw Village and moved back a few years ago, and she's well aware of the simple version of her neighborhood's story.

She points out that the economy has directed the shift in public housing discussed by Davis and that there are plenty of white families moving in, though she assures she's not talking about race when she says, "Nothing is ever just black and white if you look at it closely."

As for Savannah's enduring perceived chasms, she is cheerfully optimistic.

"People will get over these things if we have more places to connect," she says.

No one need be blamed for the plight of Yamacraw Square and its bronze statues; that just isn't productive. But next time you're downtown, maybe you'll walk across Fahm Street for a visit—because seeing and being seen is the first step to communion, cooperation and collaboration.

As for the Yarn Children, they have not only been seen but absolutely adored, their effect reaching beyond their original conception—they were a huge hit at A-Town last weekend, people fascinated as their deeper significance was revealed.

Jerome was so delighted with their decorated condition he seemed almost giddy. He confessed that though he often purges his studio of finished projects, some mysterious element had influenced him to keep these three forms all these years.

"I always thought they might have some kind of afterlife," he laughed, shaking his head as he touched the hem of Diva's dress.

The Yarn Children have yet to find a permanent home, and are, in fact, currently lording over my desk at Connect like a trio of wacky silent Buddhas. I find their presence both comforting and unnerving, as if they really could step off into the world on their own.

Now that they have seen the city from 12 stories up, who knows what they could inspire next?