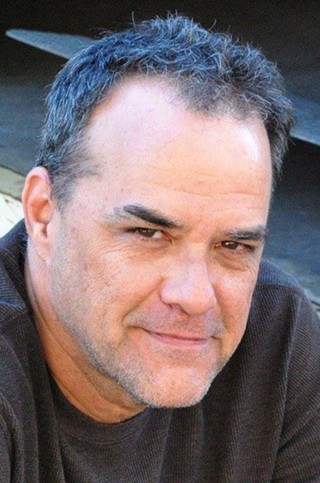

The first things I noticed about Chuck Sereika were his eyes – dark blue, distant, and sunken, set back as if they were determined to put distance between Chuck Sereika and the rest of the world. When he looked at you, it wasn’t as if his eyes were focused on you. They were looking right through you, at someone, something else.

Unimposing, dark–haired and a little stocky, Sereika barely spoke above a whisper. He was intense. I never saw him smile and I never heard him laugh.

He had a story to tell me, he’d said, about his experiences in New York City on September 11, 2001. I was working for a daily newspaper in South Florida, and as the 6th anniversary of 9/11 approached, I had asked the readers to e–mail me. Like that Alan Jackson song, I’d asked “Where were you when the world stopped turning?”

I got a few responses, but nothing particularly unique.

And then I heard from Chuck Sereika.

When he gave me the quick version, over the phone, my jaw hit the desk. He directed me online to a story the New York Times had written about him.

I made arrangements to meet with him the next day. Covering my bases, I first called the Times reporter, Jim Dwyer. Could this really be the same guy? I asked.

“From what you’ve told me, that’s Chuck,” Dwyer said. “He’s the real deal.”

In September of 2001, Chuck Sereika was 32 and living alone, with a closet full of demons, in New York City. Physically, emotionally and sexually abused as a child, he had been addicted to alcohol – and to crack cocaine – since his teens. He suffered from severe bouts of depression.

Somehow, he’d managed to become a licensed paramedic, but had resigned his job 15 months earlier, ashamed, when he began the latest in a string of stays in rehab.

In his apartment five miles from the World Trade Center, Sereika awoke to the sound of sirens screaming down the street. There was a message from his sister, Joy, on the answering machine.

“Just checking in on you,” she said. “I guess you’re down there helping out.”

Sereika switched on his television, and understood, and almost immediately decided what he had to do. He was the black sheep in a badly dysfunctional family, and his repeated failures had strained every bond he had.

Except for Joy. “Maybe it’s in my character to help people, because I’ve done it for so long,” Sereika told me. “But it wasn’t even a thought. The only reason I ended up there was because I didn’t want to let my sister down.”

He found his blue paramedic jacket, with the ID tag still pinned on, crumpled in the corner of his closet. Then he walked to a nearby hospital and hitched a ride with an ambulance crew that was just heading out to the World Trade Center.

When they arrived at the site it was 11 a.m., just after the second tower had collapsed. “It looked like a huge snowstorm in September,” Sereika told me. “Everything was just covered in this white ash. Everybody was standing around. I saw no civilians at all; it was a sea of uniforms. There was nobody to treat. There was nothing there.”

Still, he did what he could, helping paramedics, cops and firefighters pick through the smoldering rubble. Late in the afternoon, as the sun began to fade, all of the rescue workers were called down from the mountains of broken concrete, shattered glass and jagged sections of steel. It would be too dangerous to keep digging at night.

Amidst the chaos, Sereika decided to keep climbing. “I put it into my head that it was a woman and a child that were trapped,” he said. “I actually figured that their lives were probably worth more than mine. I also figured that I wasn’t going to live through this. I thought ‘There’s no way I’m coming back.’

“Because I had to crawl, from the outside, on my hands and knees. There were big spaces in the rubble, and some went down what looked like 90 feet.”

I’m going to die up here, he said to himself.

And he was OK with that.

As he stood atop a concrete slab that had once been part of Building 7, he heard someone calling to him. Staff Sgt. Dave Karnes, a retired Marine who’d driven in from Connecticut to volunteer, had seen Sereika and assumed he was a real paramedic. “Thank God,” Karnes cried. “The rescue team is here!”

Karnes pointed his flashlight into the crushed remains of an elevator shaft, and Sereika peered into the darkness. Karnes had heard a faint voice; it was Will Jimeno, a Port Authority police officer who’d been covered by concrete, steel and rebar for 10 hours, and had all but given up hope.

Sereika crawled towards the sound. “I reached for my cell phone – at least, I thought, I can call my sister before I die,” he said. “It fell out of my hand, down one of the holes. It was gone – and that was it.”

Twenty feet below ground, he saw Jimeno’s wiggling fingers. “He was pinned from the neck down. I started digging him out on my own, because I didn’t think any help was coming. I wasn’t going to leave him. He was scared.”

The frantic young officer talked about his daughter, and his pregnant wife. He cried. “He was begging me to cut his legs off,” Sereiko said. “Like I could cut his legs off! He was trapped pretty good.”

For half an hour, Sereika – in a space so tight he couldn’t stand up – pulled rocks away from Jimeno, one at a time. Alerted by Sgt. Karnes, a pair of EMTs arrived, fully equipped. Sereika gave the terrified cop oxygen, and helped insert an IV drip into his arm.

It took three hours to get everything cleared away from Jimeno; in the end, the “jaws of life” were used to pry the heaviest pieces away. Sereika never left his side.

Once Jimeno had been pulled from the hole, loaded onto a stretcher and taken away for treatment, Sereika and the others emerged, their clothes filthy and in tatters, their lungs scorched from the smoke and super–heated subterranean air.

“When I came out, there was a chief by the entrance,” Sereika explained. “He goes ‘Good job, son,’ and he patted me on the back. And he gets on his radio and says ‘We need another paramedic.’ Which made me feel pretty good.”

Dazed and bleeding, Sereika disappeared into the night. He walked 20 blocks to a cousin’s house in Greenwich Village, to find his family members watching a TV recap of the daring rescue of Jimeno – and his fellow officer John McLoughlin, who’d been discovered nearby.

He told them what had happened. “And my sister said ‘Well, the TV said it was the fire department that rescued him.’ They didn’t believe me.

“So I let it go, because it’s pretty typical for my family not to believe a word I say.”

Two months later, Jim Dwyer and the New York Times, hearing rescuers’ talk about “a paramedic named Chuck” who’d just disappeared into the night after Jimeo was pulled out, found Sereika, and he reluctantly agreed to tell his story.

When it was published, his family finally believed him.

In 2004, Sereika had gone to yet another rehab facility, in Delray Beach, Fla., and met a girl there named Tracy. They married, and started a house–cleaning business in Vero Beach.

Shortly after I met him, the Oliver Stone movie World Trade Center was to be released. The film purported to tell, among other things, the story of the incredible rescue of Jimeno and McLoughlin.

Sereika had been made a “consultant” on the movie, and paid as such, but he was never asked to contribute and never visited the set. He told me he was pretty sure Paramount Pictures had done that so he wouldn’t be able to sue them for using his name.

I arranged an advance, private screening of World Trade Center in West Palm Beach; Sereika, his wife and I were the only people in the theater.

They watched the movie; I watched him. He winced and turned his head often. Mostly, he stared at the screen.

Sure enough, although actor Frank Whaley played him as a mysterious, blank–eyed paramedic in the hole with Jimeno, the character was peripheral and had little to no dialogue.

The heroic rescue was carried out by others. Stone had all but erased Chuck Sereika from the biggest moment of his life.

“It was a very long, very tiring rescue, and nothing like you see in the film,” he said wearily. “Paramount Pictures can make any kind of movie they want, but certain people know the truth. And the truth stands by itself.”

When I think about that awful day in American history, like millions of others, I think about the appalling loss of life, the needless destruction and the damage inflicted on our country’s hard–won sense of safety and well–being. I think about how the word “hero” was re-defined for us all, for all time.

And I think about Chuck Sereika.