IT WAS AN entirely different world in 1932.

Jim Crow was the law in the South, and the Great Depression had brought the world to its knees. Opportunities were few, especially for African-Americans.

But in that year two 15-year-olds, Charles L. Bailey and Mallory E. Baker, left their hometown of Claxton, Ga., to attend high school in Savannah. They were lifelong friends, and planned to room together.

The school they attended was called Georgia State Industrial College -- known today as Savannah State University. At the age of 90, Bailey and Baker still are best friends, who share a deep love of their alma mater.

Age has slowed them somewhat. Both walk with canes, but still manage to return to SSU every year to help celebrate its annual homecoming. Their minds are clear and sharp, and they can reel off names and events from 75 years ago as if they happened yesterday.

For this year’s homecoming, Bailey and Baker returned to SSU to share their memories of those times. The program was videotaped and archived, and it will be included in a documentary on Hill Hall that is being produced by the SSU Department of Mass Communications.

It’s all part of an ongoing mission to capture Savannah’s African-American history. A documentary about Martin Luther King Boulevard’s history and heritage recently was produced by SSU faculty as a part of this program.

One faculty member, Dr. Ronald W. Bailey, a visiting professor in African-American Studies and History, is Bailey’s son. “This all started a couple of years ago at homecoming,” Dr. Bailey says.

Bailey and Baker had returned to SSU, and a drive around campus prompted memories of their days there. “They started talking about Hill Hall, where they stayed,” Dr. Bailey says. “I realized we should preserve these stories.”

Modern technology makes the preservation of memories and traditions easier and more permanent than it used to be, Dr. Bailey says. He hopes that others who know people whose stories should be recorded will contact him.

“History provides us with valuable insights and lessons on how we should deal with the present and future,” Dr. Bailey says. “We are letting young people hear two 90-year-olds talk about the conditions they faced, what SSU taught them that prepared them for the rest of their lives.”

Hurricane Katrina destroyed more than buildings in New Orleans, Dr. Bailey says. “If you don’t record history properly and put it someplace safe, it can be lost,” he says. “Every day, we’re losing what is called the Greatest Generation.”

In some of his classes, Dr. Bailey is encouraging students to seek people out and ask for their stories. “Interview senior citizens in nursing homes,” he tells them. “When you go home for Thanksgiving, sit down with your grandparents.”

Students are being trained to do such interviews by learning about technology, listening skills and having a sense of the historical period so they know what questions to ask. “Students are coming back and telling me all kinds of fascinating things people have shared with them,” Dr. Bailey says.

Lenny Bailey, another of Bailey’s sons, says he never tires of hearing his father’s stories. “I feel Savannah State has been an integral part of my life,” he says. “Talk about being a living example. You can learn from him how to teach your own children.”

Natalie Johnson is a junior majoring in history at SSU. “It’s wonderful to meet roommates who were here at SSU in 1932.What events went on in Savannah in 1932? What buildings were present? What was student life like back then? How did SSU prepare them for careers?” she asks.

“History says there is nothing new under the sun and that events repeat themselves,” Johnson says. “It’s great to have these first-hand experiences and I’m thankful I have the opportunity to hear them.”

Theron “Ike” Carter is the manager of the SSU radio station, WHCJ. With Shenetha Wilburn-Solomon, he moderated the discussion with Bailey and Baker.

“I’m excited about this because there’s a lot of history here,” Carter says. “People have a lot of information and history, but if we don’t write it down, it will be lost.”

At some point, Carter plans to broadcast the interview with Bailey and Baker. “The station was devastated by a lightning strike on July 31, but the new equipment is on order,” he says.

“To lose such a valuable part of history would be a crime,” Carter says. “I’m so happy someone decided to do this.”

Baker and Bailey have known each other their entire lives. “I was born in 1917 and grew up with my mother and father,” Baker says.

“My father was in the service. Later on he passed. My mother was a widow when I was a teen. She was interested in my getting an education,” Baker says. “My mother passed very early. At 18, I was on my own because I had no family. My grandmother and grandfather had passed already.”

But his parents had instilled values in Baker that helped throughout his life. “I had good home training,” he says. “That’s where it starts.”

At that time, schools were segregated and Claxton had no black high school. That’s why Baker chose the Georgia State Industrial College, which had a high school program.

He finished high school and in 1937 was enrolled in the school’s junior college program. But Baker never finished.

“We had a scratch over the food that was given to us at the time,” he says. “We were young and thought the stuff they put in the food was bad for our health.”

Baker led other students in a demonstration to protest the situation, and at the end of the year, he was expelled. “I received a letter that told me not to report back to school,” he says. “I never did get back here.”

But Baker’s life turned out just fine. “I married and started a family and moved to Washington, D.C.,” he says. “I’ve been there ever since and I’ve been doing pretty good.”

Bailey went on to earn a degree and remained in Claxton, but the two have remained best friends over the years. “We grew up as friends,” Bailey says. “I can’t remember a time when we weren’t friends. After he left Claxton and went into the service, I don’t think we’ve missed a year without seeing each other.”

The friends packed up their entire families for visits between Claxton and Washington, D.C. Sometimes they got together twice a year.

When he was young, life was hard, but Bailey says his family had it better than most. “My mother taught school for $25 a month,” he says. “My father was a carpenter and earned one dollar a day.”

The black community in Claxton was close-knit. “I remember if someone visited Savannah, everyone would gather around,” Bailey says. “People wanted to branch out and learn more about what was in the world. Growing up was a fascinating thing for us.”

Baker met his wife at her birthday party when she turned six. “My friend was there. His mother was a teacher, and my wife’s mother wanted her to stand with the teacher’s son. After the birthday party was over, I let him know she was my girl,” Baker says, tearing up.

“We didn’t get married until several years had passed, but she was my girl from then on.”

Going to the industrial college was a huge adventure, and Bailey says they called it the College by the Sea. One of his treasured memories is of a football game with South Carolina State.

“They were so cocky,” Bailey says. “They didn’t even stay overnight. They were so sure they were going to win, they just came here that morning.”

The game was played on a Saturday afternoon in an area of campus the students called the Dust Bowl. “We beat South Carolina State,” Bailey says proudly. “The news went everywhere. Schools wanted to play us.”

The next year, the Tuskegee Institute football team was on the schedule. “The year was 1935 and they swamped us,” Bailey says.

The industrial college had two “fraternities” -- of a sort. “There were the agriculture boys and the trade boys,” Bailey says. “There was a great rivalry.”

The two groups never mixed. “The agriculture students lived up on the hill and the trade students lived in the dormitories,” Bailey says. “You didn’t get onto campus without getting involved with one or the other.”

Bailey and Baker were trade students. “In the trade department, we’d go to school in the morning and do a trade in the afternoon,” Bailey says.

Classes included carpentry, auto repair, painting and shoe repair. “With shoe repair, you didn’t have to change clothes,” Bailey says.

Students from all walks of life attended the college, from the children of the very wealthy to those whose parents were servants. “Living in Hill Hall was nice at that particular time,” Baker says. “Having come from a little school, it was very good to be able to associate with other fellow students.”

Social life at the college was quite active for both groups, even if there was just one telephone in the entire building. “The only calls you could get were calls coming in,” Bailey says. “There was an annual trade dance and an annual agriculture dance. The social life meant more to the agriculture boys.”

Women attended the college, too. Students were given two hours each day to sit on benches and talk.

“The women lived in the dormitories, and some lived with teachers just off-campus,” Bailey says. “It was a very close-knit community.”

Baker was studying economics when he was kicked out of school. “I wasn’t concerned about being expelled,” he says. “I just wanted conditions for students to improve.”

Even in their protected world, Jim Crow sometimes showed its ugly face. Bailey remembers when in 1933, the Georgia Board of Regents brought Dr. George Washington Carver to speak to the students.

One of the board members stood up to introduce Carver. “He introduced him with the ‘N’ word,” Bailey says. “He did not hesitate.”

Students gathered afterward to express their anger and concern over Carver’s treatment. But there were opportunities that wouldn’t have happened if it wasn’t for the college.

“When President Roosevelt came, we all got to watch the parade,” Bailey says. “A lot of things were done to improve our pride and show us there is another way of life.”

At the college, the students were accepted and fiercely protected from the rest of the world. There were curfews, strict rules and standards, and even bed checks. “I didn’t have too much contact with Jim Crow,” Baker says.

The students made up the largest part of the community, Bailey says. “Education was not a plaything here,” he says. “It was a way of life.”

Each day was structured and students were expected to stick to the schedule. “The chapel seats were marked,” Bailey says. “We had chapel every day, and sometimes we had noon-time assemblies. Every Sunday, you’d go to church. We did everything we could to get noticed, even sing in the chorus. Religious life was stressed.”

An empty seat was noted, and instructors were deeply invested in their students, Bailey says. “The interest the instructor took -- they invited us to their homes,” he says. “They really tried to instill skills into you.”

Students respected instructors, and instructors respected students, Bailey says. Times were hard then, yet students didn’t drop out or turn to crime.

“I wonder what’s wrong with our young men, particularly our young black men, today,” Bailey says says. “I can tell you where I come from and where I’ve gotten to. Here it was impressed on us to see the world in a different light.”

Looking around Adams Hall, Bailey explains that it was the dining room when he and Baker were there. “It’s where they had the social dances,” Bailey says.

“The teachers stood up above and looked down and told us who was dancing too close,” he says. “They’d call your name, too.”

That kind of guidance is needed today, Bailey says. “Parents in today’s society don’t take the time to rear their children and provide the nurturing that is needed,” he says.

Four generations of Bailey’s family have been at SSU in one capacity or another. Baker and Bailey always return to for homecoming. “We come year after year to support our alma mater, and we do it with great pride,” Bailey says.

Homecoming was held in the 1930s, too. “We didn’t have an all-out do like they have now, but what they had was enjoyable,” Bailey says.

“Former students would come back and tell you their successes and what they were doing,” he says. “It gave you inspiration.”

Do you know someone whose story should be recorded for future generations? Dr. Ronald Bailey wants to hear from you. Call 303-4357 or 356-2151.

To comment on this story e-mail us at

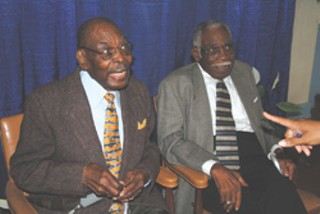

Mallory E. Baker and Charles L. Bailey speak in a program which will be archived as part of Savannah State history