THIS WEEK, the Smithsonian Institution will open its nineteenth museum: The National Museum of African American History and Culture. Inside, artwork from one of Savannah’s most important local artists is already on display.

William Pleasant Jr.’s (1928-1997) seminal painting “The Huckster” has joined the museum’s permanent collection and will be a part of its “Cultural Expressions” exhibition, scheduled to be on view for at least the next decade.

On the museum’s website, the show is described as “an introduction to the concept of African American and African diaspora culture.” The National Museum of African American History and Culture is the only national museum devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life, history, and culture.

For Pleasant’s descendants, the museum’s acquisition of “The Huckster” represents a significant victory in their battle to gain recognition for his artwork.

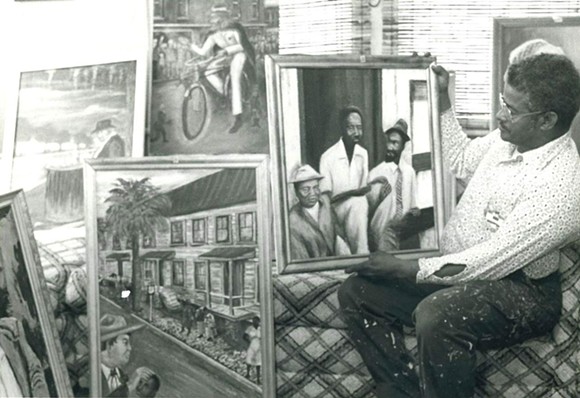

You’ve seen William Pleasant Jr.’s art, you just may not know it. His hand-painted signs still adorn City Market, the Savannah Visitor’s Center complex and Beth Eden Baptist Church. Less publicly visible are his paintings.

Though Pleasant worked consistently throughout his life as a commercial artist, he left behind a trove of fine artworks (occasionally autobiographical) informed by the legacy of Gullah Geechee culture and the struggle for civil rights in Savannah.

Some of Pleasant’s paintings have found their way into the collections at the Beach Institute, the Ralph Mark Gilbert Civil Rights Museum and King Tisdell College, but they are infrequently exhibited to the public.

I really can’t understand why.

Not only was Pleasant’s sign artwork an integral part of Savannah’s visual landscape (as it continues to be to this day), his paintings depict the cultural experience of the city’s African American residents with remarkable sensitivity, depth of symbolism, and narrative sophistication.

Whether painting a genre scene of a jazz quartet outside a movie theater or a civil rights protest, the historical significance of Pleasant’s artwork is undeniable.

“He was a person who came through lynching, segregation, black power, burgeoning new Jim Crow, the violence that happened during the Reagan administration... And his consciousness went back even further because our family has been here since the 1850’s at least,” Pleasant’s son, David Pleasant, told me.

The Pleasant family has deep, deep roots in Savannah.

Louis Pleasant, the artist’s great-uncle, was one of the co-founders of the Savannah Tribune (then called the Colored Tribune) in 1875. William Pleasant Jr. himself was a collaborator of civil rights activist W.W. Law as well as one of the earliest members of the Savannah NAACP. And, of course, he was a prolific painter, producing paintings of Savannah genre scenes and depictions of African-American and Gullah Geechee life for decades.

Yet, Pleasant’s relatives have found it nearly impossible to gain recognition from local arts institutions for their father’s artistic contributions.

“There’s been a general denial of him having any artistic ability,” Jalal Pleasant, another of William Pleasant Jr.’s sons, explained.

“We’d like there to be proper representation of the indigenous people in Savannah who contributed heavily—especially like my dad over the years—to Savannah. No other artist in this region painted like him, nor did they document the landmarks and people and events of Savannah or its history.”

According to his sons, Pleasant’s artwork is not represented in any major museum collection in Savannah.

Additionally, one of the artist’s only surviving murals (a painting located on the Barnard Street School building containing historically significant scenes related to indigenous Savannah culture and African-American life) was painted over by SCAD in 1988 when the building was renovated to become Pepe Hall. Pleasant’s sons say they were not notified that the artwork would be destroyed.

The Smithsonian Institute’s interest in Pleasant’s paintings has not come without a sense of vindication for the artist’s descendants.

“The Huckster,” the artwork that has now been inducted into the museum’s collection, is a particularly robust demonstration of Pleasant’s strengths as a painter. Steeped in symbolism, the piece contains volumes of information.

“It’s a really powerful statement about [his] whole life—his life in Savannah, about African-American culture in general and about Gullah Geechee culture specifically,” David told me.

When I pushed him to elaborate on the historical import of the piece, he paused for a moment and closed his eyes.

“It’s not about the history behind “The Huckster.” There’s history in it,” he said.

At first glance, “The Huckster” may appear to be a modest portrait of an African-American fisherman selling crabs on the street. Deeper exploration reveals much, much more at play.

Not only is the painting significant for its historically accurate rendering of Frogtown (once a thriving African American business district), it also utilizes Gullah Geechee concepts of duality and tension to introduce complexity into its visual narrative. The gender-ambiguous figure opens their mouth in a silent shout. Standing at a crossroads, their black skin shines bright in the dark night.

“It’s about the pain, the passion, the joy, the struggle,” David says.

“Dad never just wanted to paint something pretty. He was never like that.”