“The best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago. The second best time is today.”

—Ancient Chinese proverb

SKY-HIGH sycamores, papery crape myrtles, gargantuan live oaks crowned with outstretched branches—trees are undoubtedly some of the Lowcountry’s most famous residents, and a hardy few have been here far longer than any of us.

While a handful of old giants have survived for more than 250 years, Chatham County’s iconic urban tree canopy is around a century old, mostly the result of trees planted after the Sea Island Hurricane wiped the coast clean in 1895.

Those towering oaks, sweetgums and magnolias that shade Savannah’s streets and squares have enchanted generations and serve as a lovely marketing tool to attract visitors and development.

But our local trees do much more than lend charming ambience and cool respite. They sequester carbon from the atmosphere and prevent the ground from sliding out from under us, saving the county over almost $600 million a year in air pollution reduction and stormwater infrastructure costs.

The canopy provides a habitat for a diverse collection of bird, animal and other plant species and has been linked to a variety of public health and socioeconomic benefits.

It’s also disappearing at a rate of four acres a day.

That’s the alarming takeaway from “An Assessment of Urban Tree Canopy of Chatham County, Georgia” conducted in 2014 and available to the public earlier this year. Made possible by a grant from the Savannah Tree Foundation and conducted by Colorado-based geospatial mapping company Plan-It GEO, the Chatham Canopy Assessment reveals that 36 percent of county land is covered by trees, down from 50 percent in 1992.

Aerial photography comparisons indicate that the county has lost over 21,000 acres of canopy since 1999.

“We know we’re losing trees,” says Savannah Tree Foundation Executive Director Karen Jenkins. “The question is, how do we mitigate that loss?”

STF has been at the forefront of Chatham County tree advocacy for almost three decades. Acting as the official stewards of the Candler Oak and informing policy for local governments, the non-profit also hosts regular volunteer planting and mulching sessions throughout the county. Jenkins recently led the students of May Howard Elementary in a clean-up day for a hundred STF trees planted a decade ago.

But its efforts aren’t enough to stop the attrition documented in the report, which states that for every acre of tree canopy lost, 70 trees need to be planted and grow to maturity to offset it.

“If every PTA would spend two hours on trees instead of baking cupcakes, the world would be a better place,” sighs Jenkins, noting that there are over 1500 acres of available land on the county’s public school campuses.

STF does outreach and education about the importance of trees, and Jenkins points out that the City of Savannah has met the canopy loss proactively with the adoption of a Complete Streets policy and a Park & Tree Dept. that plants a third more trees than it removes each year on public property.

“Urban forests don’t just happen. There’s a lot of management going on,” she says. “The city is doing its part. But it’s also up to individuals and property owners to plant trees and take care of them.”

New commercial development is the biggest threat to Chatham’s trees, a trend driven by the explosive growth of Southside Savannah and Pooler. Balancing the county’s economic interests with its arboreal resources is one of the challenges put forth by the canopy assessment.

That requires viewing the canopy in “environmental, social and economic terms,” and the assessment recommends an umbrella urban forest management plan for the county’s nine municipalities, from Pooler to Tybee Island.

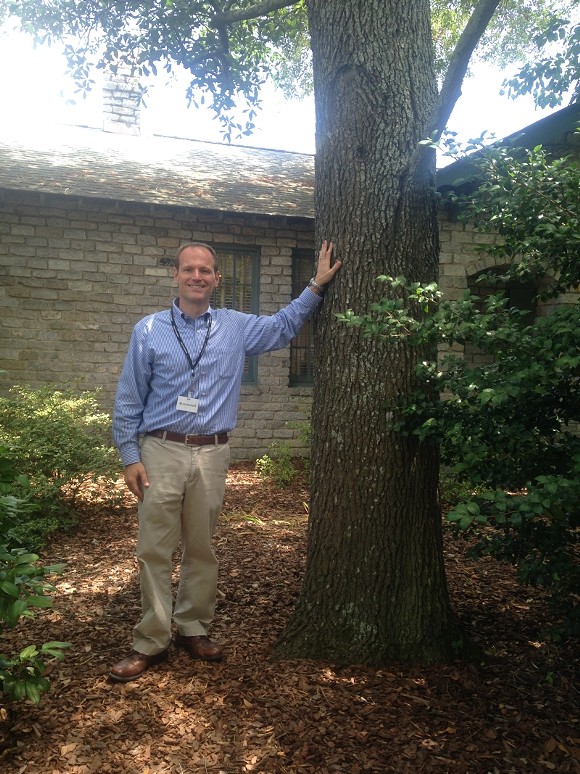

But growth is good, reminds City of Savannah Park & Tree Director Gordon Denney. While the canopy loss statistics are distressing, they’re also the result of new housing, shopping districts, schools and ballparks in parts of the county that were once inaccessible.

“You have to remember the Savannah Mall, the annexation of West Chatham—the numbers reflect places that were just woodland when the canopy was assessed in 1992,” says Denney, who has worked at Park & Tree since 2001 and took over as head of the department in May.

As a Savannah native and a graduate of UGA’s landscape architecture program, he’s concerned about canopy loss. But he also accounts for marsh and water when reading the statistics and takes a measured view on the future.

“I tend to see the glass as half full,” he says. “Yes, it’s an alarming trend—if you aren’t managing under a good tree ordinance.”

While most of the county’s municipalities enforce some type of oversight regarding public trees, the City of Savannah’s Landscape and Tree Protection Ordinance is by far the most comprehensive. Denney helped craft the most recent version back in 2007 as well as a set of revisions adopted in February that call for expanded regulations, improved compliance and measures to preserve Savannah’s biggest, oldest specimens.

The tree ordinance applies to single-family, multi-family, commercial and industrial development, and its revisions include moving it from the Public Services header to Planning and Regulation of Development to clarify that protection is its first intent.

Definitions have been changed and added, including a new designation of “specimen tree” that preserves mid-growth canopy trees over 24” in diameter.

Private homeowners are still allowed to do as they please on their own property, but commercial developers now have more stringent guidelines to follow if they want to remove trees from an area. To help developers realize the value of accommodating trees instead of removing them, the revised ordinance also contains increased incentives:

Within the landscape quality point system that governs development projects, specimen trees are now given a higher value of 2.0 instead of 1.5 for preserved retention factor, and the value of “exceptional trees” has jumped from 2.5 to 3.0.

“If we don’t save these middle-aged trees, we’ll never have anything exceptional,” says Denney.

Any healthy tree “of notable historic interest, high aesthetic value or of unique character” can be deemed “exceptional” after being recommended by a neighborhood association or Park & Tree and approved by the city manager. The process protects the tree in perpetuity on public and commercial property.

Currently, the live oak incorporated into the landscape of Critz BMW on Abercorn is the only designated exceptional tree on the books.

An “exceptional” sticker still doesn’t protect a tree that’s rotting or dying, and Denney gently reminds that even most stalwart trunks will eventually succumb to age.

Urban forestry requires pruning and sometimes removal in the interest of public safety, and many trees in the canopy have reached peak maturity.

Addressing the concern that the city preemptively cuts down older trees to avoid lawsuits—like the one that resulted in a $9.5 million settlement in 2013 after a dropped branch took a woman’s leg and caused permanent brain damage—Denney shakes his head.

“This is my home. My grandma would give me an earful if she thought I wasn’t doing right by this city.”

Pests, disease and heavy traffic can shorten a tree’s lifespan, and part of the department’s mission is to remove ones that pose a threat to public safety.

Denney explains that in most cases, the city replaces a removed tree with a sapling of the same species; however, it takes time—decades, in some cases—for a new tree to fill in the same patch of canopy.

“A live oak can’t grow in the shade of a live oak,” he says. “Unfortunately, you can’t underplant for the next generation.”

Is it possible to catch up? The assessment predicts a drop to 23 percent in canopy coverage by 2050—more than 40,000 additional acres—if trends continue “business as usual.” Urban forestry professionals are doing everything they can to stave off that dramatic a decrease in greenery.

“I know we’re losing trees, but the study really brought it home,” says Mike Pavlis, an arborist certified by the International Society of Arboriculture and owner of Ossabaw Consulting.

Pavlis is often called to verify a tree for removal or preservation and counseled on the irreversible decay that forced the city to bring down the controversial Victory Oak on East 41st Street last year. He also provides consultation on commercial projects.

“Smart developers incorporate existing trees as much as possible,” he says. “They see that trees add value; they’re not just placeholders.”

He encourages private citizens to plant trees themselves, though he’d like to see more diversity and less “go-to” species like crape myrtles and red maples.

A member of the Coastal Arborists Association, Pavlis is also aligning with other arborists and foresters to better educate the public and to advocate for best practices within municipal governments.

(The CAA is hosting Dr. Kim Coder of UGA’s Warnell School of Forestry for a lecture this Friday, June 12, and the public can join Jenkins in representing the trees at the county budget review on June 18.)

Faced with the data put forth by the canopy assessment, Chatham County has much work to do to stave off an arboreal crisis in the next 35 years.

The good news is the study shows 44,000 acres open for planting, and neighborhoods with less than 20 percent tree coverage could benefit immediately from a countywide planting and preservation strategy.

“We have a premiere urban forestry program here, and the elected officials need to understand that how important it is to our economic future,” says Pavlis.

“People come here for the trees. My goal is to save as many of them as I can.”