A few years ago on a chilly morning, I looked out my bedroom window and saw a young man I didn’t know standing amongst the azalea bushes in my front yard.

He was dark–skinned and wearing a hooded sweatshirt, craning his head back and forth as if searching for something.

He started to walk around the side of the house where we keep the chickens. My stomach plunged. A flurry of possible actions bounced around my brain: Should I call 911? Sic the pug on him? Hide in the pantry and whimper helplessly?

Finally, I just opened the door and said in my Big Bad Mama voice, “Hello, can I help you?”

He jumped back from the fence, looking startled.

“I’m with Georgia Power. I’m here to read your meter,” he said, pulling back his hood to reveal a handsome face and a winsome smile.

I looked him over, arms crossed over my pajamas, unconvinced. “Where’s your uniform?”

He unzipped his sweatshirt to reveal a red vest with the utility company’s emblem on the chest and held up a badge.

“Sorry, ma’am, it’s cold out here today,” he apologized, his breath steaming in the crisp air.

“Sure is, Mister —” I took a look at the badge — “Taft.” I stood there feeling like a douchebag, all noodley from the adrenalin of the perceived threat and the relief that it’d come to nothing.

I also felt like I owed him an apology, too, though I wasn’t quite sure why. Until he showed his ID, he’d been a stranger on my property, after all.

He was way ahead of me. “Don’t feel bad, I can see why you might’ve been scared. I should be wearing this thing on the outside,” he said nervously, quickly taking off the sweatshirt and vest and reversing their order.

The understanding flooded my consciousness that as a black man whose job entailed poking around between people’s homes, Taft probably went through the rigmarole of explaining his presence multiple times a week, maybe a day.

No matter how professional and affable he came across, I sensed that he faced suspicion from certain people as he went about his business. For him, forgetting to keep his uniform visible could mean having the cops called on him, or on the worst day, taking a bullet.

Unable to erase the injustice of it all, I lamely offered the only thing I could: “Want a muffin?”

He laughed and refused, but from then on, we’d wave at each other when he came ‘round to count up our kilowatts.

Sometimes we’d chat about the hawk that stalks the chickens. Even the dog stopped barking at him, an honor reserved for family members and those carrying snacks. But no matter how cold it was, I never saw him wearing a hoodie again.

Since 17 year–old Trayvon Martin was shot to death a month ago by an overzealous vigilante, I’ve been thinking about Taft a lot. We’ve all been thinking about what it means to mistake an innocent black man for a criminal.

Several pieces have circulated nationally about the painful “talk” many African–American parents have with their sons about society’s perception of them, including a piece by Jesse Washington, a race and ethnicity reporter for the Associated Press. In it he attempts to explain to his 12 year–old boy that he must always be aware of his actions, writing, “Understand that even though you are not a criminal, some people might assume you are, especially if you are wearing certain clothes.”

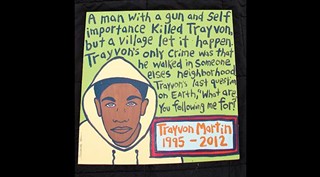

While the same could be said for trenchcoats and Muslim headscarves and the suspicion attributed to their wearers, Trayvon in his hoodie has become a national symbol for mistaken identity and misplaced fear. Artist Scott Stanton, aka Panhandle Slim, captures that in his painting of Trayvon, shared coast–to–coast on Facebook last week.

Stanton, renowned for his folk–art portraits of famous figures, felt compelled to memorialize Trayvon out of frustration over the senseless killing and the uncomfortable knowledge that something similar could happen very close to home.

(Georgia, like Florida is one of 20 states with a “stand your ground” clause that perhaps gave George Zimmerman the bravado to shoot and may protect him from prosecution.)

“This could happen in my own neighborhood here in Savannah,” Stanton told me. “We have a neighborhood watch in full effect, and we have neighbors that proudly announce they have guns to protect themselves. They warn us about ‘them’ coming into our neighborhood.”

“What do you mean by ‘them’?” he asked.

I admit to being willfully naÏve when it comes to race. Living for a long time in a liberal bubble in Northern California, I had hoped racial tension had gone quietly out of style, like shock treatments and feathered hair.

I have come to understand that there are those who cling stubbornly to their ignorance and fear, though I find them to be fewer and far between, I think because, as Washington wrote in his article, “America is better than that.”

In my neighborhood, I try to be wary without being prejudiced. When someone, anyone, walks down my street that I don’t know, I catch his or her eye and raise my hand, and call out that requisite “Heyhowyoudoin.” Mostly, I get back a hand up and the boomerang “Finehowyoudoin.” I make a lot of friends that way.

Did the fact that Taft was black affect my initial fear of him that morning? I don’t know. The truth is I would have freaked out on anyone in a hoodie on my lawn, because honestly, I think hoodies instantaneously transform everybody into looking like methheads.

Would George Zimmerman have followed a white kid through his gated neighborhood? No one knows. But surely the outcome would have been different if he had just said, “Hello, can I help you?”

The lesson here is that there’s no such thing as “us” and “them.”

There’s only you and me and our willingness to swallow our fears when we meet face to face.