One of the most fascinating — but curiously little–known — chapters of military history came during World War I in Belgium.

In an attempt to break the stalemate of trench warfare, British, Canadian and Australian miners, most of them civilians, spent more than a year digging 22 tunnels under German lines.

At the end of those tunnels they put a fantastically huge amount of explosives.

You see where this is going.

In June 1917, the charges were detonated under a section of the Messines Ridge, a place known only as Hill 60 from its name on military maps.

The explosion — at that time the largest detonation in history, heard as far away as London — instantly killed or buried tens of thousands of German troops and broke through a key sector of the German line. The topography remains altered to this day.

The Australian film Beneath Hill 60 portrays the real–life experience of Oliver Woodward, commander of a group of Australian civilian miners recruited for the Western Front tunnel projects. Woodward leaves behind his own mining firm and his young sweetheart Down Under to serve his country.

With an outstanding Aussie cast (led by Brendan Cowell), darkly compelling cinematography, and a tight storyline, the $10 million film gives little indication of its comparatively low budget, taking you not only behind the front lines but under them to the riveting atmosphere as the tunnelers race against time to finish their lethal engineering.

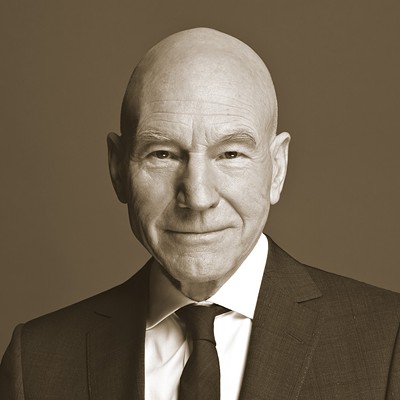

We spoke with screenwriter David Roach about his work on the film.

How did you decide to base a script on Oliver Woodward’s story?

David Roach: The original story came from a diary that was discovered by a miner in far North Queensland, a diary written by Oliver Woodward just for his family. Without that diary — which was about to be thrown out, by the way— no one would know this story, because the whole mining project was a big secret at the time.

The second reason we wouldn’t know about it was that military mining was considered ungentlemanly at that time. The “gentlemanly” way to fight in those days was you gathered in a line and an officer blew a whistle and you all advanced forward across No Man’s Land. Sounds ridiculous now, but in those days that’s what it was like.

Another reason this story would have remained hidden is that when all the other troops came back at the end of the war to victory parades, these miners and tunnellers stayed on and helped rebuild Europe, since they had so much engineering expertise. When they came back, all the victory parades were over.

Why did you think it necessary to use flashback sequences of Woodward’s time in Australia?

David Roach: It was inevitable for this particular film, because to make a whole film set in tunnels and trenches in the mud and blood of the First World War would be intensely claustrophobic for the audience. You need that claustrophobia to build pressure and tension, but you also need some sunshine. You need a little bit of breath.

The story about the women is also extremely important to me. When I was researching this and found out that the real Oliver Woodward did actually fall in love when he was 26 and Marjorie was 16, it got me thinking that that sort of thing must have happened all the time. Not just in Australia, but wherever a soldier went off to war, young women would fall in love with them and promise to marry them when they got back.

Of course the man that came back was a completely different man from the one who left. My feeling is those women had a completely different kind of courage than the soldiers, and that needed to be expressed.

You also break first–person narrative to show the experience of a young German miner involved in constructing counter–tunnels to the Allied projects.

David Roach: When the Germans started to be blown up by Allied tunnels, they went to Bavaria, found some coal miners, gave them rudimentary training, and sent them to the bloodiest battlefield in history. The tragedy is that in any other situation these two groups of miners would have had lots to talk about together.

When the concept was brought to me I decided one of the things I didn’t want is one of these war films where the enemy is just evil shadows. I wanted to show that the Germans had families and feelings and memories of their own.

Why is World War I so important to the Australian psyche, as opposed to say World War II when you were actually under threat of invasion?

David Roach: When you’re trying to finance a project and are seeking funding, normally what happens is you pitch the story, they look at you and say “What’s in it for us?” With this, we’d say this is a story about World War I, and before we could get to the next sentence they’d say “Oh, my grandfather served in World War I,” or “My uncle was killed at the Somme.” Because such a huge proportion of males in Australia went to the war, the male population was pretty well devastated. And because enough time has passed, there’s a lot of romanticism associated with that war.

Australia was a British colony then — we’re still a part of the Commonwealth — and the attitude was if anyone was going to attack Britain, then we were going to help our mother country. It’s an old–fashioned notion now, but in those days we wanted to prove ourselves.

A lot of these men went to that war because it was a great adventure. Most had never left Australia and many had never traveled beyond their communities. By Australians participating in that war, it changed us forever. From that point on we considered ourselves more independent, and we wouldn’t venture into a war without a lot of thought.

Where did you shoot the battle scenes?

David Roach: We shot the entire film in Townsville, on the coast of Queensland. Many of the real characters in the story came from this little mining town. There was tremendous interest there because of the shared history. We got an intense amount of community support.

We found these older women in their 80s who had beautiful handwriting and got them to write the letters to the front from loved ones. They’d ask, “What should we write?” and we told them no one’s going to see it close up, write whatever you want. Several times on set when the actors opened these letters and read them, they got all teary because what these women had written was so beautiful, and so appropriate.

We needed extras with no limbs to portray wounded soldiers. All that’s done with computers these days, but that’s very expensive if you have a moving camera. That was well beyond our budget. So our producer went on the radio and said, “If any of you has lost a limb, if you want to come help us we’re filming this scene tonight.” I was completely embarrassed!

But the afternoon before the all–night shoot, these men turned up. Some were veterans of very recent wars, Iraq and Afghanistan. One man had lost both legs only a few months earlier and was just starting to learn to use artificial legs. They all said “We’re here to help.”

About four in the morning we gave them hot soup and blankets, and the crew gave them a round of applause. One of the men said “We did it for those blokes.” I thought he meant the actors.

He said, “No, we did it for the diggers. The miners.” You realize that spirit the veterans have goes all the way back. Hopefully that spirit made its way to the screen.

Beneath Hill 60 screens Monday, Nov. 1 at 2:30 p.m. at the Trustees and Thursday, Nov. 4 at 2:30 p.m. at the Lucas. David Roach will attend both screenings.

.