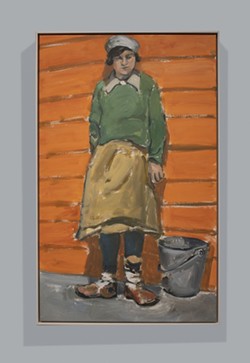

In "Other Youth," painter Marcus Dunn dives into his Native American heritage by painting from photographs.

Dunn, a member of the Tuscarora Nation of North Carolina, used found candid photographs to tell the story of Native American boarding schools at the turn of the 20th century.

He’s influenced by painters like Alice Neel to take the artistic liberty of adding or removing elements from his work.

“Other Youth” is his first solo museum exhibition and is on view through Nov. 3 at the SCAD Museum of Art.

We caught up with Dunn last week.

1. How did you get the idea for this body of work?

When I was working on my MFA here at SCAD, I’d already started thinking about doing this for a while. I was referencing a lot of Native American imagery I was finding randomly. It was all imagery of Native people that weren’t in traditional attire; I wanted to capture them in what they were like post-reservation life and how they were adapting to these new situations they were in.

I wanted to find something I could latch onto that people didn’t really know a lot about that history. Going through some statistics, 87% of schools in general do not cover Native American history past 1900. Once the majority of them went to reservations, they stopped talking about Native Americans. The Indian War ended right at the 1890s, and there was the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890. Most people just learn about Native history up to that and don’t acknowledge what the Native people went through.

Even myself, I was learning about it through the process of searching for images, reading up on different schools and learning through visuals of what people’s life was like through a lot of candid imagery. You can read about certain things, but you don’t really see the faces, you don’t see what the people looked like and what they were experiencing.

2. How did you find the images you used?

A lot of the images I found weren’t really put out there; only certain people that were maybe linked to the schools had access to them, but now they’re posted online. I have the ability to make these images.

Some of these images aren’t exactly like the photos. I’m throwing in things that I feel are going to help with the painting.

I felt like I could do some isolation painting, and I do a lot of referencing to paintings in general. I was thinking a lot of people like Edward Hopper, who captured that mood of loneliness.

Right now, I’m leaning towards putting less and less in the photos that I see, thinking more about creating my own narrative.

3. What’s it been like to work towards a new style?

I’ve always felt like I needed a visual reference as a crutch, almost. With these works, there were a lot of choices I made that weren’t there. When I did my MFA show, I felt like everything was more controlled, like they were more photo-referenced. They felt more like Luc Tuymans or Marlene Dumas, like straight from photo reference. That’s what I’m trying to get away from now. It’s something I feel is going to help my work and take it in other directions.

I’m constantly looking at paintings that do that. One in particular I reference a lot is Alice Neel, who’s using a visual reference but also so many techniques in her work. She’s using so many other things out of her imagination. I love that.

4. Your reference photos are candids of Native American life, not portraits in their regalia. Why did you make that decision?

It’s almost refreshing to see that, especially from a time period like that and referencing a source that was hardly ever photographed in that way. Whenever you think of images of Native American people, you think of Edward Curtis, who did the really famous sepia tone photos of Sitting Bull and Geronimo. Big figures like that that people know, and they see them in their full regalia. But they’re still living in society and people kind of forget to acknowledge, they’re also living in urban society.

5. Tell me more about your background with the Tuscarora Nation.

I’m the youngest of five kids, and my family started in the 70s going to powwows. In the early 80s, we started really working with our local community. A lot of people weren’t participating in the local songs and dances, and we started getting involved with the Six Nations up north. We told them we’re working to revitalize our culture down south in Pembroke, North Carolina.

Back in the early 80s, my family along with other people in our community got involved with those guys up north and they helped us revitalize those traditional songs and dances, which are called Iroquois social dances. They’re thousands of years old. We started a dance troupe and we’d go around to different festivals and perform those dances. That was a big thing, a big part of my childhood.

To this day, I still go back home whenever we have ceremonies. I don’t get to go as often as I’d like because I live in Indiana now, but this year I was head male dancer at our 39th annual powwow.

It’s really important for me to continue those traditions. We also have quite a few people working on the Tuscarora language that basically died out in North Carolina a while back. It’s necessary for our ceremonies because we have to have things spoken in the language during the ceremony that we couldn’t actually do properly before. That’s a big thing for us. A complete loss of language loses our thought process of who we are. When you can speak in it, you can think in it, and it becomes more of who you are. It also helps with your ability to be confident in your skin, with your identity as a native person.

I struggle a lot being someone that’s mixed native and also coming from a community that’s been dissimilated over so many years. I do feel a little [insecure] in my identity when I attend the reservations where the culture is really strong. I went to school in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and the culture is really strong there. You see they have so many things, you wish it was like that in your community, but it’s a great thing now that we’re able to bring these things together. That they feel there’s an inclusion with me being there, I can feel accepted and it does make you feel great to have that, but it’s also like, “Man, I wish history was a little different in our area.”