She may be new in town, but Sharon Norwood is certainly an artist to know.

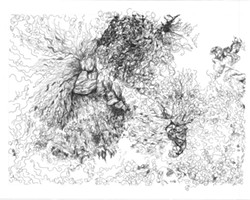

After getting tired of the figure as her subject matter, Norwood pivoted to line. Hair is everywhere in Norwood’s work, from drawings of braids to split ends on china sets. Her work calls into question our relationship with hair, particularly the hair of black women, and makes a strong statement without being overtly political or heavy-handed.

We caught up with Norwood last week.

1. How long have you been in Savannah?

I’ve been here about a year and a half. It’s such a roundabout thing. The best thing you can do, after about seven years of being married, is you turn to your husband and say, “You know what, I’m going back to school.” So I went back to school and got my MFA. He got a transfer here to the Air Force base, so that’s why I’m here.

I do like it here. All these schools are here, the art culture is here. I feel like Savannah is an old place with a lot of history. There’s a flux that’s happening; it feels like it’s constantly on the cusp of becoming something. I feel that the space is also good for my work because my work touches on a lot of historical narrative, colonialist type stuff.

2. How does Savannah inform your work?

This place we bought, when we got there, we found all these different things like old pictures; I think there were some African-American ladies from the 1800s in the images. Some of those images ended up inspiring some of the themes I’m working on—histories and roots, even just walking along the waterfront and seeing the ballast walks.

My work is normally based on imagined histories, so some of it’s not real history, or history you’ve learned but you don’t realize you’ve learned. Sometimes my work lives within that space. I don’t necessarily research and make work, so being here allows an organic way to come across these stories and for it to be a part of the work I make, as opposed to being research-based or studying a book. “I’m reading this story about Harriet Tubman, and now I’m going to make work about Harriet Tubman.”

The work is there, but it’s layered. You can come to it in a certain way and take something else from it. I’m touching on specific issues, but I’m not forcing my audience to think a specific way. And I’m a visual artist, so there’s a visual aesthetic. I’m not just a historian. I’m bringing an identity to these old stories. I’m always trying to put myself in those conversations, with my body being referenced in these specific ways.

3. How does your use of hair in your pieces tie into that?

When I first started making work, one of the things I wanted to talk about was things that are distinctly African-American. How do I discuss the thing without using the figure? How do I reduce these markers to the lowest common denomination, where people can still read it in this specific way? I was doing figuration a lot and wanted to get away from it. The line, the hair—that gave me the chance to speak about these issues but also make work that, even though it’s political, I can still be making work that for me isn’t political. I’m making this work as a black woman but I’m not necessarily talking about these very harsh subjects all the time. Sometimes it’s just about drawing this curly thing.

In undergrad, I was making all this stuff and couldn’t concentrate on a thing. I kept doing all these different things. But once I found the line, I’ve been completely centered.

4. Tell me about the process of finding the line.

I was making clay masks that people enjoyed, but I got really sick of making them. I wasn’t inspired by them anymore. It was taking so long, the process of making and painting, that I was just like, I’m going to do ink and paper. At the time my hair was falling, I was always finding hair around the house. I decided to do a still life of my hair that’s fallen. When I first started drawing the hair, I didn’t know if it would render as hair. When you’re drawing hair, you can’t look away or you’ll lose your mark, so it became this meditative process of trusting the line, all that stuff I heard in undergrad.

After I made about 13 drawings, my godson walked in the room and was like, “Sharon, how did you get the hair on there?” So I started inviting my friends over, and my African-American friends were like, “Oh, yeah, that’s hair when it’s fallen off the brush.” To me, when I started hearing those stories, it was just so inspiring—they see it.

With certain things, you have to teach the audience how to see. I became very interested in that. I’m going to try to teach my audience how to see, and if they see this as hair, then that will free me to be able to take this further.

5. What do you hope people take away from your work?

For me, the work seduces you visually. You think you’re looking at this very pretty thing, and you get in closer and you’re like, what the hell? You’re left alone with your thoughts and ideas about the thing, and you have to negotiate your way out of it. You have to think, “How do I feel about this? Do I feel this work has merit? And why do I feel that way?” But it’s a conversation you have with yourself—it’s not a conversation you’re having with me.

We remove hair, we don’t want evidence of hair, and the work just keeps giving like that. It’s so layered in terms of how we look at hair being dirty. If you put race into it, it’s a conversation about domesticity or labor. African-American hair has become such a big subject matter in art, and even though I use hair in the work, it’s not just about hair. It’s not just about this material of hair, it’s more in a sense that I’m able to teach my audience how to see.

It speaks to something bigger than ourselves. However many hairs you’ve shed, where did it all go? There’s this thing that sort of brings us back to our humanity or aybe something bigger than ourselves. That’s one of the things about the work that makes it so I can’t move on to anything else. I’ve got to keep working.