MANY LOCAL theatre fans saw the recent broadcast at the Lucas Theatre of Ian McKellen’s King Lear, direct from the Duke of York's Theatre in London.

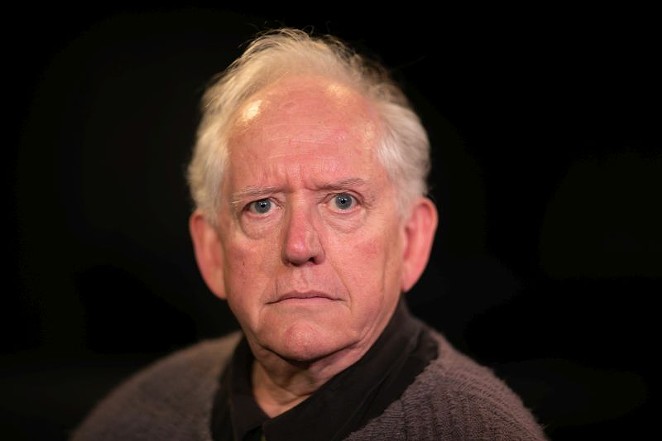

Dennis Elkins — who plays the title character in Savannah Shakes’ upcoming production — not only saw McKellen’s Lear, he saw it live in the UK.

“I thought Ian McKellen’s performance was even more human than Olivier’s,” recalls Elkins. “That’s the part we often miss in Shakespeare. People so often elevate these iconic characters to the point where they lose humanity. McKellen’s performance at times is heartbreaking.”

A professional Equity actor, Elkins has never taken on this particular role, however. “The closest I’ve come is playing Gloucester in Boulder, Colorado,” he laughs, referring to an earl in the play who is blinded for his loyalty to Lear.

Many argue that King Lear is the greatest of Shakespeare’s tragedies, and his crowning achievement in terms of language and insight.

Continuing Savannah Shakes’ tradition of modernizing The Bard’s work, director Karla Knudsen says, “Our Lear is set in the doomsday/Y2k panic of 1999, so the sense of urgency and unknown is palpable with our particular tribe. We’ve used the Rajneesh, Jonestown, and Heaven’s Gate cults as a jumping off point.”

Lear is an aging king near the end of life. Deeply narcissistic, he sets off a competition between his three daughters: The one who loves him the most will get the most of his kingdom.

His youngest and favorite daughter, Cordelia, refuses to take the bait, saying her love for him is so great that mere wordly power and possessions pale in comparison.

Her offended father disinherits her, setting off a vicious cycle of treachery, banishments, and brutal assassinations, as the two other daughters, Regan and Goneril, plot both with and against each other, along with their husbands and lovers, to secure power.

“We keep coming back to Lear’s entitlement and why he has such a following,” says Knudsen. “He’s a benevolent leader that has never been told ‘no.’ So we’re finding the differences between the world within Lear’s realm/control versus the world outside.”

For Elkins, the main challenge with Lear is the sheer elevation of the king’s language.

“I pace myself, in part because of the language. It’s a very heightened language,” Elkins says. “It’s not just that he uses the royal We and Us a lot, it’s the fact that the language itself is very flowery and poetic. I want to make sure and honor that poetry while trying to get it to make sense to a modern audience.”

Knudsen echoes that sentiment.

“King Lear sits in our collective memory as that daunting epic diatribe on aging and madness. Nobody wants to spend two hours in that. Yet, to deny the tragic is just silly,” she says.

“Because Lear’s world goes off the rails so quickly — in the first four pages — it’s necessary to suss out his world when in stasis, and to establish history in a moment so we understand later what is lost.”

As for directing Elkins through the daunting prose, “Lear often speaks the sudden shifts in his interior dialogue,” Knudsen says.

“Usually the actor crafts these sorts of beat changes internally, so we are enhancing some of those moments with flashbacks, lighting and sound. And Dennis is the master of connecting text to movement which provides strong offers to his fellow actors.”

The fulcrum of the play is what is known as Lear’s “madness,” a scene during Act II in which he reaches the depths of rage, despair and self-pity after Regan and Goneril essentially emasculate him by stripping him of his knights, and of his power and dignity.

However, for centuries audiences and scholars alike have questioned how insane Lear really is during the scene.

“I disagree that it’s a real madness,” says Elkins. “In a sense he’s just a stupid old man! His ‘madness’ comes from grief, and the fact that he thought he had everything all worked out, but he really didn’t. He thinks he’s never wrong, and no one ever tells him no.”

Director Knudsen says, “Lear’s awareness of his actions fluctuates: from raging protest to his daughters’ patronizing to full-out hallucinations to extremely lucid assessments of his sanity. He even confides in his Fool at one point, ‘Oh, let me not be mad.’”

In the end, Knudsen says, “I’ll let the audience judge, moment-to-moment, if Lear has lost it or not.”

Of course, a story is only as good as its villain, and King Lear boasts several of the best in literature, chief among them the horrifyingly cynical and savage daughters Regan and Goneril.

“In painting the world of Lear, we explore the villainy, manipulation, dark side of every character. And that’s by design — Shakespeare often gives the word ‘villain’ to the so-called bad-guys throughout the play. But so is the word ‘fortune,’” says Knudsen.

“The antagonists are important because, if we are all ‘the natural fool[s] of fortune,’ they are as justified in their choices as the heros. The antagonists provide much of the humor, combat, and all-out gore in our production,” says Knudsen.

“And that’s just fun. Chris Soucy and Travis Spangenberg are building some particularly villainous fight choreography.”