THANKS TO the erasure of African-American history, it can be easy to forget the fact that the civil rights movement happened in some of our lifetimes and that the people we read about in history books are not that distant of relatives to living people.

“For me, it was my aunts and uncles!” says the Beach Institute’s Alicia Scott. “It’s easier to want to forget about it, but we’re talking about it. We’re trying to shed a light on a culture that has created a massive system of disparate treatment.”

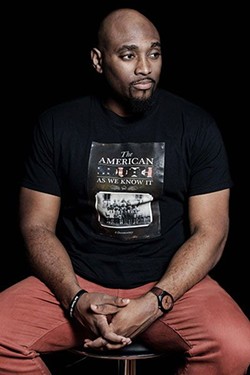

One way the Beach Institute is shining that light is through its screening of “The American South As We Know It,” a documentary by Frederick D. Murphy.

Murphy is the founder of History Before Us, a project that preserves influential history. As part of that project, he traveled around the Southeast interviewing people who had survived the Jim Crow era, which inspired him to begin filming the documentary.

“In the film, they’re interviewing people who talk about what it was like growing up in the segregated South,” says Scott. “As children, they actually witnessed the KKK and racism.”

As most know, racism is by no means over, and its effects are still seen today.

“There are parts of Alabama that they say are worse than a third-world country,” says Scott. “The UN has come in and condemned these rural areas where there’s raw sewage, no plumbing. We talk badly about other countries, but there are rural parts of the South where, because of the disparity and the greed of the local government, these people live in almost the same conditions as slavery.”

“The American South As We Know It” shows those silos of Southern inequity in a thoughtful way. The film is making its way down the coast, showing in Charlotte, North Carolina, and Charleston before screening in Savannah.

“Of course, it’s showing in this historic Gullah-Geechee heritage corridor,” says Scott. “We just officially became a partner in the Gullah-Geechee heritage court. We’re excited about that—it’s going to add texture, as I call it, to our community, since everyone loves tourism.”

This film screening kicks off the Beach Institute’s new documentary series.

“Starting in 2019, we’re going to show a different documentary at the Beach every month,” says Scott. “Some will be old documentaries that the public doesn’t know much about. It’ll all be centered around something unique to Savannah or the South, based on African-American heritage and the African diaspora.”

“We want to pay tribute to the arts by showing documentary. We want to have intelligent discussion around it, and the best way to do that is through film,” says Scott. “It creates a benign environment for people to look at hard subjects and topics like this. That’s what we wanted to do with this film.”

While Scott notes that not all the films in the series will be as heavy as the first one, the goal of the series is to get everyone in the community together to watch. Since people of all races will be watching together, Scott and the team are careful to foster discussion afterwards that serves as a debrief of sorts.

“We really don’t want people to leave feeling despondent. That’s one of the things that make it difficult for both black people and white people,” explains Scott. “It’s part of the racial reconciliation that goes both ways. White people leave a film like that covered in guilt. Black people leave feeling angry. We don’t want you leaving angry because if anger and guilt are both leaving, you’re both going out on the streets and you bump shoulders and it escalates into something because it leaves you with all these feelings.”

As part of that racial reconciliation, the Beach welcomes everyone to their safe space to watch and learn together.

“We want people to come here and be who they are,” says Scott. “When you come to the Beach Institute African-American Cultural Center, you can come and be whoever you are, and you don’t have this question of cultural appropriation because it’s showing at the Jepson Center or wherever. When we saw the Jepson showing ‘I Am Not Your Negro,’ we thought, ‘We really should be showing that. We should be doing it and make it free.’”