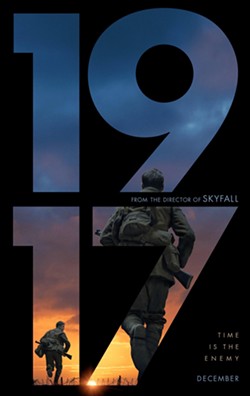

Review: 1917

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "14680855",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "14680856",

"insertPoint": "15",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - SVP - Leaderboard - Inline Content - 2",

"component": "16852291",

"insertPoint": "10",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "10",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - SVP - Leaderboard - Inline Content - 3",

"component": "16852292",

"insertPoint": "20",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "18",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - SVP - Leaderboard - Inline Content - 1",

"component": "16852290",

"insertPoint": "25",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

1917

**** (4 out of four)

The latest from director Sam Mendes (Skyfall, American Beauty), 1917 ranks second only to Marriage Story as the best picture of 2019 and second only to Saving Private Ryan as the best war movie of the past quarter-century. As for films seemingly shot in one continuous take, it has more competition but still manages to emerge near the top of the heap.

While the act of filming a movie so that it appears to be one continuous shot can admittedly be construed as a mere gimmick, it’s actually a sound way to showcase the possibilities of cinema as an immersive, envelope-pushing experience.

What’s more, the technique has been placed in the service of some genuinely good films, thus enhancing and expanding their own individual accomplishments. These titles include Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope, the Best Picture Oscar winner Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance), and Russian Ark, the latter actually filmed in one single take rather than just being crafted to appear that way.

For 1917, Mendes has teamed up with the best of the best, cinematographer Roger Deakins (Blade Runner 2049, Sicario, and no less than 12 movies with the Coens). Along with the efforts of other key behind-the-scenes personnel, they have created a mesmerizing exercise in technical prowess, a World War I saga in which the camera takes us across the battlefields, through the trenches, underneath the surface, and straight into the heart of darkness that blackens every wartime encounter.

Deakins’ camera alternately follows the action from in front and from behind, swirling just enough to add to the occasional disorientation that surely must arise from such harrowing circumstances. Adding to the ambience is the magnificent score by Thomas Newman, perhaps only, yes, second to his work on 1994’s Little Women as the best of his impressive career.

Yet 1917 is more than just a visual and aural assault on the senses. The story, co-scripted by Mendes and Krysty Wilson-Cairns, takes the standard “men on a mission” template and infuses it with an idealistic zeal. Its heroes are Lance Corporal Schofield (George MacKay) and Lance Corporal Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman), who are tasked with delivering a message to a battalion stationed behind enemy lines.

It’s a crucial missive whose delivery will save lives, as it relays the information that the Germans are planning an attack that will catch the advancing soldiers off-guard and lead to their wholesale slaughter.

What follows is a trek across hostile terrain, as Schofield and Blake press forward even as the odds in their favor shrink infinitesimally. There are encounters with allies, encounters with the enemy, and, during one of the film’s few oases of calm, a poignant encounter with a Frenchwoman (Claire Duburcq) who remains in hiding with her tiny baby.

Since the two leads are largely unknown (although MacKay has been around since 2003 and Chapman appeared as Tommem Baratheon in several episodes of Game of Thrones), a number of known actors fill the supporting ranks. Among these, Andrew Scott makes the biggest impression as a wisecracking lieutenant, with Benedict Cumberbatch, Mark Strong and Colin Firth also fine in their small roles as officers of varying temperaments.

With the emphasis on conflict, war movies often have to dig deep to unearth any semblance of humanism amidst all the carnage and callousness. In 1917, that apathy is front and center, in ways that both surprise (the interlude with the Frenchwoman) and shock (a sequence involving a downed German pilot). War may indeed be hell, but 1917 is a war movie whose soulfulness elevates the picture into something approaching grace.