I'LL never forget the first time I met Jack Sherman.

It was early 2005, and he had shown up at the Sentient Bean Coffeehouse to attend a public screening of Sam Peckinpah’s graphic 1971 thriller “Straw Dogs,” which I was presenting as part of my Psychotronic Film Society of Savannah’s weekly series of underappreciated cinema.

He was knowledgeable about obscure movies, and I could tell through his nervous and cautious demeanor that he was restless and desperately seeking a personal connection with someone who shared these interests.

Afterwards, I invited him to join me for a drink around the corner at the American Legion. For a couple hours, we stood close in animated conversation — the topics shifting rapidly at a frenetic pace.

It felt as though he believed this meeting might somehow be our last, and was scrambling to make sure no stone was left unturned.

All night long I’d felt an odd sense of déjà vu, as though we had not only met before, but had previously enjoyed some strong connection. When I asked what he did for a living, he said only that he was a musician, but did not play much anymore.

Once he offered his full name, I suddenly felt something akin to the tumblers of a massive combination lock to a bank vault sliding into place.

“Wait a minute,” I said. “Are you a guitarist?” He seemed taken aback and warily replied in the affirmative.

“You’re ‘the’ Jack Sherman?”

“Well,” he said with a suspicious look, “I mean, I don’t think you’d know any of my work.”

“You played the solos on ‘The Man with the Blue Post-Modern Fragmented Neo-Traditionalist Guitar?’

(That was a relatively obscure 1989 solo LP by singer-songwriter Peter Case, perhaps best known as the frontman for California’s short-lived but immensely respected psychedelic-tinged power-pop group The Plimsouls.)

“Um, YEAH!” he replied, his eyes as big as saucers. “That WAS me.”

It turned out Jack, his wife Anne and their two children had relocated to Savannah’s Southside about a year earlier from the Los Angeles area, after he’d become disillusioned with not only the harsh realities of the rock and soul music business (which he’d labored in full-time for decades), but with the particular treatment he himself had begun to receive from gatekeepers of that cliquish, cutthroat, backstabbing industry.

He and Anne had “thrown a dart in a map” and swapped coasts. But more than that, he’d essentially given up his life’s work and the dream he’d often previously accomplished: being a full-time, professional guitarist on stages and on records.

After an especially ugly and drawn-out legal battle over unpaid royalties (which he was clearly due for his work as the sole guitarist on the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ debut LP and as a co-composer of several tracks on a couple of their later releases), Jack’s resolute insistence on being treated fairly from a financial standpoint by both that band and their label (after being treated quite unfairly from a personal one) left him in an unenviable position.

L.A.’s a big city, but it can feel an awful lot like a small, gossipy town when you’ve got the nerve to stand up for yourself and essentially demand redress from one of the biggest record labels —and one of the most popular acts— in the entire world.

And so, the Miami native who’d wisely made Southern California his base of operations for decades packed away his myriad, beautiful, rare and sometimes custom-made guitars and resolved himself to a quiet life of solitude, housework and haltingly exploring the cultural offerings of his new, slower-paced hometown: a location which —for someone of his caliber and pedigree— was about as far from being a hotbed of musical opportunities as one might imagine.

I think the fact that I found Jack’s time in the Chili Peppers perhaps the least interesting aspect of his impressive career and accomplishments endeared me to him, as that was all that roughly 90 percent of anyone under the age of 70 who met him wanted to know about.

I mean, he got it. And he appreciated it. He understood that being a key member of that group at a formative time in their history was truly important to a lot of folks.

And, it was important to him, too. Just perhaps not in the same way, or for the same reasons.

But to me, he was the guy who played on countless —and I mean countless— uncredited studio sessions, accompanying the likes of Solomon Burke, Barry Goldberg, Gary Mallaber, Moon Martin, Jim Keltner, Bruce Gary and all manner of R&B, funk and rock greats.

And he was the guy who made incredibly tasteful, credited (and in some cases featured) contributions to albums by respected singer-songwriters like Bob Dylan, Tonio K, Gerry Goffin and P-Funk’s George Clinton, among others.

He was the guy who Dylan’s manager asked in 1988 to serve as lead guitarist and bandleader for the small, tough, punk-edged power-trio that was to be the first incarnation of Bob’s famed Neverending Tour Band, but who sadly lost that prize of a gig at the last minute after a chance encounter with SNL guitarist G.E. Smith at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame ceremonies led to Dylan changing horses in midstream.

He was the guy who toured hard in the trenches with John Hiatt before that esteemed songwriter ascended into revered elder statesman status.

He was the guy with the impossibly high hairdo who can still be found on YouTube in blurry VHS videos holding his own on guitar alongside the great Charlie Sexton at MTV’s “1986 New Year’s Rockin’ Eve” (which I recall watching live).

He was the guy who couldn’t read music in a conventional sense, but could leave even the most accomplished and classically-trained guitarists slack-jawed and beaming with admiration for his seemingly effortless technique and improvisational skill.

That technique was far from effortless, though. Jack routinely spent several hours each day practicing, or simply playing electric guitar in his home – trying out different combinations of guitars, amps, strings, effects pedals and batteries. (Yes, like the fabled fret-master Eric Johnson, Jack was one of those rare, absurdly observant guitarists who could occasionally tell which brand of battery was inside an effects pedal solely by the infinitesimal difference in tone it was creating.)

He would often call me up in the middle of the afternoon simply to gush about how he’d come up with a great new sound by combining a certain guitar with a certain cable into a certain amp and using a new combination of specific EQ settings.

So, without asking first to see if it was in any way convenient, he’d immediately put his phone down near the amp and just play guitar very loudly for several minutes, after which he’d ask me to describe to him in great detail what I thought about the tone. I know I was not the only person he reached out to in this way.

Of course, the fact that this entire exercise was essentially useless because the sound was being not only transmitted via cell tower but picked up and then heard through tiny telephone microphones and speakers made no difference to him.

He just wanted to share, and to know he’d been heard.

In the end, that’s what I’ll remember most about Jack: his desire to be heard — either through his knowledge, his opinions, his voice or his music.

And his emphatic desire not to be misunderstood, which he quite often was.

Jack had a difficult upbringing, and as is often the case, those trials and tribulations followed him all his life. This left him saddled with a combustible and at times chaotic personality that was equal parts hubris and insecurity, equal parts solemnity and bombast.

He could be charming one moment and biting the next, sometimes in the course of a single, impossibly long run-on sentence.

This was confusing to most, bewildering to others and genuinely annoying or infuriating to some.

It also had the unfortunate side effect of often rendering him incapable of noticing (or at least admitting that he noticed) the same flaws in himself that he loudly railed against others around him for demonstrating.

As a result, many in this area who met Jack tuned him out or wrote him off, never having the patience required to get to know his good points as well as his bad. Those of us who did could not be faulted for feeling a certain pride in that accomplishment, a certain kinship borne of struggle.

He went out of his way to create strict regimens, codes and schedules to give his life order and purpose. To some these may have seemed arbitrary, but to me they clearly seemed designed to keep him focused and thus distracted from the inner turmoil which plagued him.

And woe be unto anyone who even accidentally upset that apple cart!

Jack was keenly aware of the difficulties he faced in making (or keeping) friends, and we spoke of it often. In more relaxed and lucid moments, he would offhandedly admit that he assumed he was “probably on some sort of spectrum,” and that he realized he was a dramatic and demanding person who was fixated on the notion of life as an essentially transactional existence.

Meaning he believed that all of a person’s deeds for someone else –good, bad or otherwise– required something of similar value or import to be exchanged in return.

Dealing openly and honestly with the friction such issues created meant that ours was a tumultuous friendship marked by occasional dark times and rough patches. Yet we spent tons of meaningful time together and always circled back around to the deep connection we made on that very first night at the Legion.

I could clearly see that all of his psychological and emotional armor was built up to ward off any further pain in his life.

And, most importantly, the obsessive and monomaniacal behavior which could sometimes keep potential friends (and friendly acquaintances) at bay fed directly into his musical talents – especially his gift for jazz-like improvisation.

He detested rehearsing musical material, as he was most at peace and most clearly happy when creating music spontaneously, on the fly. I always felt it was in the fury of those brief moments that he was able to instantly and automatically ignore the various vexations which beset him, and to silence the constant buzz of criminations and recriminations in his head.

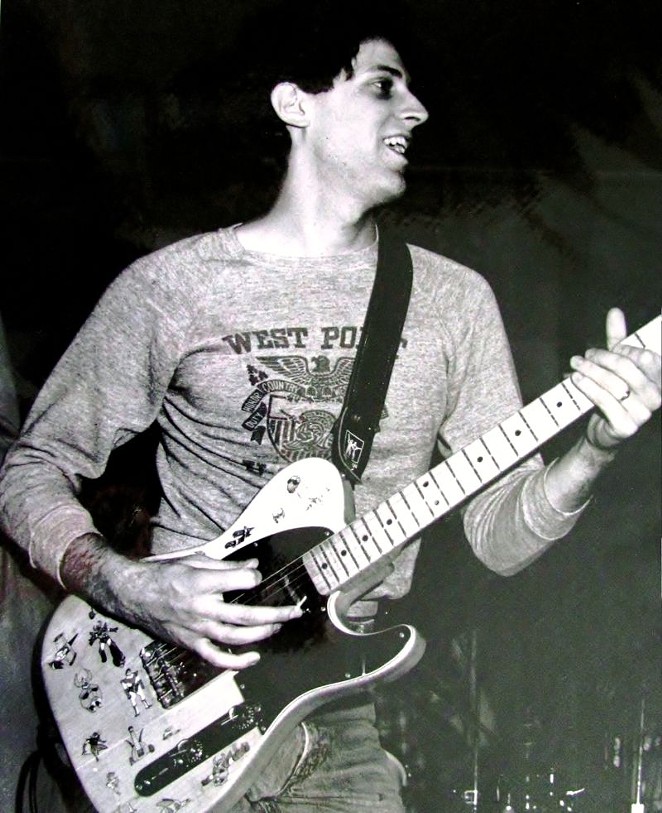

Just look at live video of Jack performing. He often pulls faces, giggles or laughs outright, apropos of nothing other than a whimsical turn of melodic phrase or the sheer joy of playing music with others who could not only hang at or near his same level of proficiency, but spur him on to greater heights.

You can even see it in still photographs. He’s in heaven.

Jack passed away unexpectedly the evening of August 18, at his home, of natural causes. His death creates a huge hole in the local music community, and that hole is made even larger by the fact that so many of this area’s musicians and music lovers are quite unaware of just how unique and priceless a talent he was.

His relative inability to carve out greater success and visibility in our scene over the past 16 years is partially due to his rigid viewpoints and frustrating focus on minutiae (which often got in the way of building the kind of camaraderie required to ingratiate oneself into an existing scene), but it’s also the result of many players and songwriters in this town who simply had no idea how to relate to such an “unmatchable genius” (in the words of legendary punk guitarist and songwriter Sonny Vincent) who’d been unceremoniously dropped into their midst.

If someone asked me to describe Jack Sherman in one sentence, I’d first ask if they were relatively familiar with American TV show characters of the 1970s through the 2000s. If they were, I’d tell them he was a cross between Carl Kolchak, Adrian Monk and Les Nessman who could play guitar just as well as Carlos Santana, Mick Taylor, Steve Hunter or Bob Elsey.

The official public statement on his passing from the Red Hot Chili Peppers was unsurprisingly terse, and only feeds into the false narrative the group’s duplicitous frontmen, Flea and Anthony Kiedis, have pushed to their fans for decades: that Jack was nothing more than a combative and ephemeral sideman who did little to shape the group’s music or its career trajectory.

Which is balderdash. But, I suppose that’s the kind of revisionist history you get when two immature, long-term drug addicts wind up hiring a sober, macrobiotic health-food nut that’s laser-focused on playing perfectly, getting the job done every night and has no time for their junkie business.

However, I’ll always recall the time Jack’s name came up in conversation with the late great guitarist and singer-songwriter Duane Jarvis (who’s played with John Prine, Lucinda Williams, Frank Black Francis, and others).

“Oh, I’ve heard of that guy,” Duane exclaimed. “AMAZING guitarist... and a real piece of work.”

When I mentioned to Jack that an acclaimed songwriter and fellow player had been complimentary towards his talents, he demanded to know what Duane had said.

“Tell me all of his exact words,” he insisted. When I reluctantly did, Jack was crushed. All he could focus on was the second half of the sentence.

But here’s the deal: we’re ALL “real pieces of work.” Some of us just do a better job than others at hiding that fact.

Around that same time I met legendary bassist and record producer Jeff Eyrich (who’s played with, or made albums for Tim Buckley, Bette Midler, Air Supply, Natalie Cole, John Cale, Rick Springfield, The Blasters and T-Bone Burnett, among others), who had used Jack on numerous recording sessions for a variety of both established and up-and-coming artists.

Jeff said with great sincerity, “Jack was always the absolute best electric guitar player in Los Angeles, and I wish he’d never left. I’d be hiring him constantly!”

Think about that for a minute.

That’s like calling someone the best pizza chef in New York City.

And knowing how much Jack appreciated a truly great pizza, I think it’s actually a compliment he would have been comfortable with.