JOHN T. EDGE knows a little something about Southern food.

His credentials run a mile long: a three-time James Beard Award winner director of the Southern Foodways Alliance, contributing editor at Garden & Gun, columnist for the Oxford American, and other appearances dot his impressive resume.

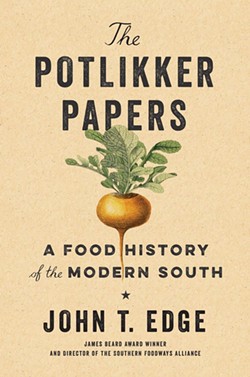

His newest book, The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of the Modern South, chronicles the timeline of Southern food, from the 1950s to today, with a special bent towards how minority groups have been essential in the evolution of the South.

Edge will speak at the Jepson Center on Sat., Feb. 17 at 12:30 p.m.

We spoke with Edge about what Husk means for Savannah, how food is politicized, and, yes, Paula.

How did you decide you wanted to write this book?

I’ve been trying to write it for twenty years [laughs]. I've been writing about Southern food culture for that long, always trying to get at the issues that define our region and vex our region. Racism, gender inequity, class difference. I always believed and said that those issues challenge the South in ways we never suspected.

The challenge here is to use food as a way to explore identity in the South, and that takes you to Georgia Gilmore. Ms. Gilmore was a midwife and a cook and as a young woman laid track on the railroad. Out of her kitchen in Montgomery, Alabama, she raised money for the bus boycotts that catalyzed the civil rights movement.

As opposed to me telling people about the South, I hope the book shows a character like Georgia Gilmore and recognize that the progress the South has made has been driven in large part by people of color and women.

One of the best ways to make sense of that is to recognize that those people of color and women have been cooks and waitresses and they, too, have been part of the change of the South.

That’s one of the things this book documents, from a place that was wrecked and is now in recovery.

How does the book focus on Savannah?

I focus partly on Mashama Bailey at the Grey. Mashama is an equity partner at the Grey, and her example, not as a hired gun but a a proprietor of one of the most dynamic and important restaurants in America today—there’s an answer to some of these questions in her partnership with John Morisano. One of the futures of the South can be found in that old Greyhound bus station in charge of two lunch counters.

I think about a long series of women who have defined Savannah food and it’s Elizabeth Terry in the 1980s with Elizabeth on 37th, Sema Wilkes and the African-American cooks who worked beside her [at Mrs. Wilkes Boarding House], and Paula Deen more recently. I hope that twenty years from now, we’ll remember who Dora Charles is and forgotten who Paula Deen was.

So let’s talk about Paula Deen.

It took me a long time to untangle what that means. I’ve gotta think about that issue in light of recent reporting about John Besh in New Orleans and Mario Batali in New York.

Those reports reveal that kitchens remain sites of inequity and there’s a line that connects Paula Deen’s treatment of Dora Charles to these allegations of sexual mistreatment of women in restaurants. One is defined by racism and one is defined by gender discrimination, but they’re equally important.

I know I’m just a pasty white boy, but if I can get other pasty white people to pay attention [laughs].

We can take a stand with our money.

Dining out is our favorite leisure activity, and this is about real money. Honest cultural definitions in this moment and restaurants matter more now in our American self-definition than they ever have.

I think that food commodity is coming to a close. I think all of our buying decisions are being politicized. They always were political, giving someone money is a political act because you allow them to do something. I need to understand to whom I am giving this money.

Is food ever just about food?

Sometimes food is just food and I don’t want to freight everything, but I do believe we should be aware of all the cultural complexities that define our relationship with food.

Husk just opened in Savannah and I see you profiled Sean Brock.

Sean did something bold when he opened the first Husk in Charleston and the same philosophy applies to the Savannah location. He privileged Southern ingredients, artisans, and farmers and he said that the goods that originated in the South and the artisans and farmers who work in the South are as good at what they do as anyone in the world. He instilled new pride in Southern provender.

The brilliance of multiple Husks is that each location is supremely focused on the locale in the South that it claims. Each weaves this very specific narrative that stitches together a portrait of the South so now, by way of restaurants in Georgia and the Carolinas, he’s helping consumers and other chefs inspired by him redefine what Southern food is, and that’s an important thing to do.

What does that mean for Savannah?

What that means for Savannah is that now, Mashama and Sean are in conversation about how you define Southern food culture. So are Cheryl and Griff Day and the people at Nairobia’s Grits and Gravy.

All those places are in conversation with each other as we define what Southern food is. They are both for people who live in Savannah and people who visit Savannah, actively defining what Savannah food culture is today. It’s not just about the facade of television personality, it’s about real work being done in kitchens.

It’s about SAAFON, Southern African American Farmers Organic Network. It’s a constellation of people doing good work in Savannah. And the arrival of Husk means all those entities will likely get more attention.