IF YOU’VE been following Savannah’s ongoing struggle to balance development with quality of life, you’ve noticed many storylines beginning to come out of the Thomas Square/Midtown area.

There are reasons for that.

As the Landmark Historic District continues to be retrofitted for the tourism industry — with most residential property there now de facto commercial property for Airbnb use — a steady exodus of residents is moving south to the next historic neighborhood that is (or was) reasonably affordable: Victorian-era Midtown, now called “Mid-City” in some circles.

It’s not only the number of people moving to Thomas Square/Midtown that contributes to the debate; it’s the type.

Precisely the young professionals most likely to want to “live/work/play” in Savannah’s Historic District are also the ones most likely to have settled in the Victorian District instead due to cost pressure.

In some ways, this population is now fighting a second, and probably also futile, battle for the neighborhood as high-dollar investment continues to roll south inexorably toward Victory Drive — not just along Bull Street, but inevitably also down Waters Avenue and MLK Jr. Boulevard.

Join the club. Some have been fighting that fight for an even longer time.

A classic example of the increasingly bitter divide is the recent 6-3 vote by City Council to allow the controversial Starland Village multi-use development at Bull and 38th Streets.

There was really little chance it would be denied, since the neighborhood association was at least nominally in favor of it and a pro-development mayor and majority on City Council left little doubt they were behind it.

Even Alderman Bill Durrence, elected on a platform of wise growth in that district, said in support of the project:

“If [the developer] walked away tomorrow... somebody else will come in... at one point the Landmark District, if you go back far enough, was nothing but cottages. Scale changes, context changes.”

As a friend suggested, can you imagine Durrence saying the same thing about a five-story modern building proposed for almost an entire block of, say, Broughton Street, further north in his district?

As is often the case, there was one voice largely missing from the debate: The voice of marginalized longtime residents, most of them African-American and many of them elderly, who already had to deal with significant change in the neighborhood with the first wave of gentrification.

I generally think the word gentrification is often overused. Frequently it really just means “long overdue economic development.”

But when development not only represents economic change, but also very rapid social and cultural change, that’s when gentrification begins to take on its real meaning.

The important thing to understand is this is all part of a much bigger picture as America in 2018 continues to make a rapid recovery from the recession of 2008.

Locally, this has ramifications way beyond the bounds of Starland:

Many of the constraints and restrictions on development in the downtown Historic District have long since been overturned — or more frequently, just ignored by elected officials.

Unfortunately that horse left the barn long ago.

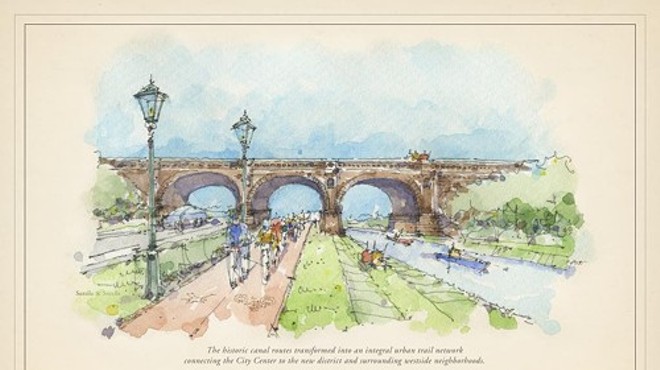

Due to Savannah’s rare ability to expand geographically both east and west from downtown, there is now significant expansion of new construction planned for the east (Savannah River Landing) and for the west (the new arena and “Canal District”).

Crucially, both expansions are outside the Landmark Historic District and therefore not realistically subject to many restrictions at all.

What I’m saying is: Hang on to your hats. You ain’t seen nothin’ yet.

In the meantime — and this is arguably the most underreported story in Savannah — low-income populations, mostly African American, are being priced almost completely out of the city center and are also moving steadily south.

As a result, Southside Savannah is attracting and will continue to attract an ever-bigger share of the one-third of city residents who live at or below the poverty level.

Simply put, the massive development focus on the downtown Historic District has had a serious ripple effect throughout the city.

Ironically, the Savannah Development and Renewal Authority (SDRA) unveiled its “Downtown Savannah 2033” Master Plan last week in the same church on Bull Street which will be repurposed as an event space for Starland Village.

The SDRA’s Master Plan — which as the name indicates is intended to take a 15-year view out to the marking of Savannah’s tricentennial — contains many good ideas and is the result of much hard work from a lot of very capable people, along with a great deal of input from the public through a series of charrettes.

But the Downtown Savannah 2033 Master Plan is itself subject to the complex and frustrating issues stated above, and is in a way as noteworthy for what it leaves out as for what it includes.

For example, as the name implies, it conspicuously doesn’t include Southside in its scope, arguably the area of town most in need of competent urban planning, whether in 2033 or in the present day.

The Master Plan does curiously include affluent, almost all-white Ardsley Park as a part of what it calls “Greater Downtown” and therefore a potential beneficiary of the plan’s new quality-of-life design elements.

But the Master Plan fails to include in its scope the lower-income and more diverse areas immediately to Ardsley Park’s east and west, which are far more threatened by intrusive development than Ardsley Park itself.

Most tellingly, the only two local businesses I heard mentioned by name in the SDRA presentation last week were two black-owned businesses, Tricks Barbecue and 520 Wings.

You guessed it: those black-owned businesses were only mentioned because they would have to move to make way for one of the suggested “design improvements,” in this case a proposed greenspace in the median to separate the lanes of Victory Drive at its intersection with Bull Street.

My point isn’t to denigrate the hard work of the SDRA, or really of anyone else.

The point is that none of us — however well-intentioned — is immune to the more problematic aspects of the growth vs. quality of life debate.

One of the red herrings often tossed out in these debates is that a developer “did everything right” and “it’s a good project.”

But it’s possible that a developer can do everything right on a good project, and the project can still be in the wrong place.

As Alderman Van Johnson said in opposition to Starland Village, “This is absolutely a wonderful project — in absolutely the wrong neighborhood.”

Get ready. The era of controversial development in Savannah is, in a sense, only just beginning.