AT A proposed cost of $140 million, the Westside Arena promises to be one of the most expensive civic amenity projects undertaken in Savannah’s history.

Advocates trumpet how the arena “is already paid for” through SPLOST (Special Purpose Local Option Sales Tax), a supplemental 1-percent sales tax. Yet building the arena in the “Canal District” near West Gwinnett Street and Stiles Avenue will likely cost much more to become a functional reality.

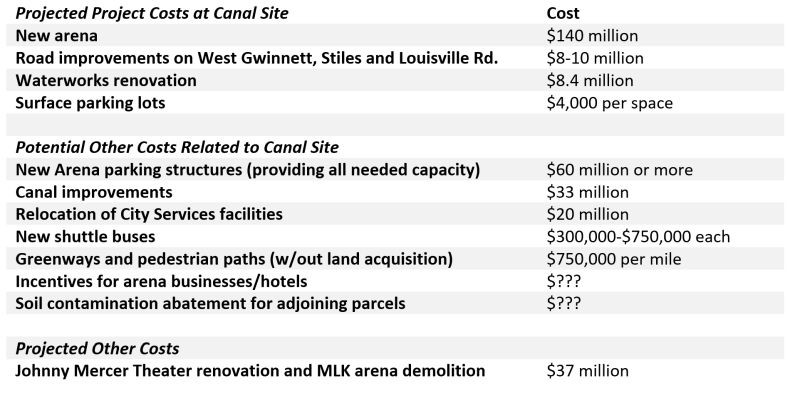

How much more? The total public investment in the area could be nearly $300 million, of which over $90 million are costs unique to this site that could be avoided with a different site closer to downtown!

How is this possible?

The tangible additional costs could exceed $130 million. As discussed in part 3 of this series, providing sufficient on-site parking will require the construction of multiple garages easily totaling $60 million.

To address flood mitigation (discussed in part 4), the consulting engineering firm Thomas and Hutton recommended the widening of the Springfield Canal at a cost of $33 million. Road improvements on Gwinnett and Stiles to handle the increased traffic are predicted to be about $9 million. To vacate the site, the city plans to spend $20 million on a new service center off Interchange Drive.

While not strictly necessary, spending $8 million to restore the Waterworks building should be a high priority, since it’s hard to see anyone building next to a decaying structure with plants growing out of the roof.

And what about the additional expense of shuttle buses, pedestrian pathways and mitigating soil contamination? New buses needed to move attendees can easily run $500,000 each.

To facilitate pedestrian access to the site, plans include a greenway along the canal and the proposed Alice-Cohen Corridor pedestrian path.

These will require still more resources—$750,000 per mile just for construction alone by one estimate—especially if private land needs to be acquired.

Developing any of the parcels surrounding the principal arena site would entail the abatement of known soil contamination. These costs haven’t been identified, but can become extremely expensive.

The City should make abundantly clear what every element of the project will cost and how it will be paid for.

Every dollar spent on or in support of the arena, after all, has an opportunity cost: the extra policing, drainage improvements, cultural events and community services that could otherwise be applied to other parts of the city.

For all the millions of taxpayer dollars that will be spent on the new Westside Arena, its financial performance outlook is poor. While arenas have a broader public purpose and may be worthy of subsidies, the City’s chosen site for the project further undermines its ability to cover its operational costs.

By and large, arenas are a losing business proposition that require extensive subsidies for their operation, to say nothing of capital (construction) costs.

Despite its central location, the current Civic Center is no exception, losing approximately $1.7 million a year, according to the City. It is kept solvent with money from the hotel-motel and rental car taxes and historically also required general fund appropriations to further patch holes in its budget.

A set of comparable facilities provided by the city’s arena consultant, Barrett Sports Group, also lost money on average. The few facilities that do manage a modest profit are usually attached to larger complexes with convention centers or conference halls.

Yet the Barrett Sports Group predicts the operation of the new arena will break even. No consultant stays in business long recommending against its self-interest. Their analysis is based on optimistic and rather flexible assumptions, so this is hardly surprising.

They foresee the facility making about $300,000 a year upon opening, declining to $187,000 by year five. Unimpressive as they sound, these figures are based on rosy expectations of revenue on everything from naming rights, parking and advertising to the demand for premium seats.

If any of these are much less than expected or if costs are much higher than expected, the new arena will operate at a loss and require subsidies.

As the consultants acknowledge, a 10 percent drop in projected attendance combined with a 10 percent increase in operating expenses would have the arena lose more than it is now projected to make. If the current Civic Center is any indication of how the new arena will perform, the outlook isn’t good.

There are many reasons to doubt these projections of profit. Parking revenue, for one, will almost certainly be needed to pay for garages.

Savannah International Trade and Convention Center former manager Bob Coffey noted in a presentation to City Council that given Savannah’s small market size (half that of Charleston and a quarter of Jacksonville’s) and event culture, it “has been historically difficult to support premium access or membership-based activities.”

In other words, premium seats and suites are unlikely to do well in this market. Savannah, he says, sees a “cheap ticket/late ticket phenomenon” where people are accustomed to approaching the box office last minute and asking for a discount.

Yet BSG’s cash flow projections have the new arena earning almost as much from premium seating and luxury boxes as overall venue rental. None of this bodes well for the arena’s long-term financial health.

The Westside site further undermines much of the new arena’s business potential. As proposed, it has sufficient capacity to host conventions and large meetings, but utterly lacks the on-site function and service facilities like large hotels and restaurants critical to attracting those types of events. Without them, the arena can only ever be a “satellite” facility.

Even with some additional development in the area, it’s highly unlikely a premium hotel could operate profitably on infrequent arena traffic. A downtown arena, by contrast, could pull from a dozen existing large hotels within easy walking distance.

For proponents of the new Westside arena, the lack of amenities is a minor problem, since they expect the new facility to unleash a torrent of private investment. There is very little evidence to support a “build it and they will come” ethos, however.

If academic studies are any guide, a 2007 review found “the broad conclusion of this literature is that stadiums and franchises are ineffective means to create local economic development, whether that is measured as income or job growth. There may be substantial public benefits from stadiums and franchises, but those too are insufficient to warrant large-scale subsidies by themselves.”

You don’t have to look far for a relevant case in point: the current Civic Center was likewise promoted as a catalyst for redevelopment as an urban renewal project when it opened in 1974, yet its neighborhood remained quite depressed into the 2000s. Vacant or underutilized lots remain nearby even today.

Economic impact analysis is extremely sensitive to input assumptions, leading to a poor track record for real-world projects. Given the far superior location of the Civic Center, we shouldn’t automatically assume the new arena would be economically advantageous. When modeling a project, planners pay most attention to spending from out-of-town visitors drawn to arena events. These are the outside dollars that stimulate the local economy.

Unfortunately, the project consultants fail to compare their projections to existing figures for the current Civic Center—a common oversight—so their value of about $9 million a year is all but meaningless.

One could certainly argue that the current Civic Center, though showing its age, is much better positioned to attract indirect visitor spending on restaurants, bars, hotels and tours, all of which are included in the consultants’ forecasts. The net new spending resulting from the venue could be quite minimal and might even be negative.

There are several further reasons to be skeptical of any headline numbers promising millions in economic benefit. Much of what Savannah residents might spend at the new arena is money they would have spent eating out or catching a small live performance downtown. People simply substitute one for the other.

To the extent the new facility attracts business away from the convention center, it creates no net benefit; more public funds will be shoveled towards Hutchinson Island to keep that facility afloat.

And what about the current proposal to double the size of the Convention Center? How will that impact the use of the new arena?

Even if the arena could somehow defy the odds and draw substantial investor interest, there are few good options for associated development. To the north, east and southeast is extremely low-lying land that would be quite challenging to build upon (see last week’s segment).

The Carver Village neighborhood to the south and west of the site is nearly all detached homes and evicting families is hardly an acceptable option. This leaves only the arena site itself and a handful of parcels to the west across Stiles and to the south across Gwinnett.

As I discussed in a previous segment, much, if not all, of the City-owned land here will be needed for parking; even the church-owned lot to the southwest was included in the consultants’ tally of parking spaces.

With enough money spent on garages, at best a few acres might be available for development once space is set aside for roads and landscaping. On private land, the lot occupied by Savannah Steel Scaffold could have potential, but only if the owners agree to sell. For such a massive “catalyst” investment, it seems there is little the arena can actually catalyze.

The current range of plans for the new arena do very little to contribute to the long-term financial health of the city. They sink vast amounts of public funds into a (probable) loss-making asset and will likely pave over the remaining publicly held land for parking. Unless generous incentives are provided, the scheme will attract little private investment, in part because there will be few development sites remaining near the arena.

Even if sites are acquired, the available evidence suggests that arenas are poor anchors for private investment. A quick look at any comparable arena—unless it’s at the core of a large city—reveals few restaurants, bars or shops; parking lots predominate instead. This is true of Charleston, Augusta, Macon and Greenville, to name the most-cited comparables.

A city arena is an important civic amenity that draws in visitors and supports community events. Savannah deserves and needs a great facility, even if it fails to pay for its operations.

The current arena is expensive to maintain and will eventually become functionally obsolete, if it isn’t already. The point in question is whether the city is best served by a new arena on the Westside, renovating the existing arena, or building a new arena somewhere else.

Even if acquiring a new site closer to downtown required $10-$15 million, it would likely save far more in the long term by avoiding new parking garage construction, flood mitigation, and by comparison would require few road improvements. It could build on a vast network of existing businesses and lodging options.

Meanwhile, the waterworks is a glorious historic building begging for restoration. It could serve as an anchor development for an actual “Canal District” redevelopment that could evolve incrementally as demand materializes and much more on the surrounding neighborhood’s terms.

How is Savannah best served? Which financial and practical outcomes do we want? The choice is ultimately up to us.