AS ubiquitous as photography has become, it’s easy to forget its humble beginnings.

Long before the camera feature became standard for all mobile phones, photographers like Ralph Steiner were using much larger cameras to push the boundaries of what photography could be.

When the Telfair Museums was presented with a portfolio of Steiner’s work, assistant curator Erin Dunn jumped on the opportunity to show Evans and other photographers of his time who redefined the art.

Enter “The Language of Vision: Early Twentieth Century Photography,” up now at the Jepson Center. The exhibition also features three photographers from the Telfair’s permanent collection: Ralph Steiner, Manual Álvarez Bravo, and Helen Levitt.

“I’m always interested in showing the permanent collection in our spaces,” explains Dunn, “so this was a chance. Ralph Steiner hadn’t received a lot of attention in recent years, and the photographs are really beautiful. I decided to pair him with these particular artists because they were all working in the early 20th century and were in similar professional and social circles, and a lot of them knew each other.”

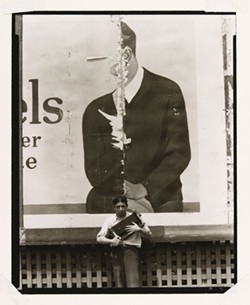

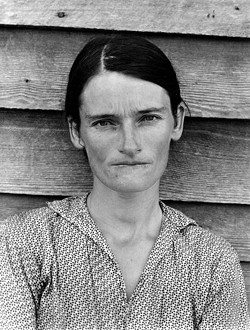

At the time featured in “The Language of Vision,” photography was mostly functional, like for staged shoots or documentary purposes. Instead of following that precedent, these artists used “straight photography,” capturing what was directly in front of them without manipulation in the darkroom.

“You had the pictorialists who were focusing on more romanticized, soft-focus photographs, and the documentary photographers trying to be factual, and then you had this group, who want photography to be a fine art,” Dunn explains. “They’re viewing the photos with their own personal vision, which is done through subject matter, the camera they’re using, the way they’re shooting, cropping, lighting—each of these photographers are looking at similar subject matter.”

Being contemporaries, the artists were inspired and influenced by one another.

“The exhibition is organized thematically, so that’s what I think viewers will get out of it,” Dunn says. “There are commonalities in the work. While they’re not necessarily working together, they’re working on similar thing. It was still an emerging art form, so a lot of the circles weren’t huge.”

One of the themes highlighted in “The Language of Vision” is street photography. Evans would go on the New York subway with a camera snaked through his shirt to capture riders, often accompanied by Levitt to make him look less suspicious. Levitt herself used what’s called a right-angle viewfinder to take pictures of the people around her without attracting attention to herself.

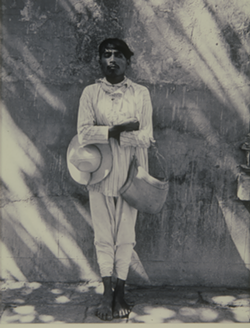

Bravo is the only non-American photographer included in the exhibition.

“Bravo grew up during the Mexican Revolution, which was a really bloody time in Mexican history,” Dunn explains. “He became part of the Mexican Renaissance, which was full of artists deciding the next phase of Mexican history.”

Bravo, completely self-taught, was discovered by Italian artist Tina Modotti, who sent his work to famed photographer Edward Weston. Bravo then became part of the same circle as Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.

“He was in that important group of artists, where he started to make those connections where his photographs could be seen in tangent with other photographers working in the United States,” says Dunn.

The title of the exhibition comes from an Evans quote appearing in the Massachusetts Review: “The meaning of quality in photography’s best pictures lies in the language of vision. That language is learned by chance, not system. ...”

“Photography allows people to think and view in a new way that doesn’t emphasize formal education,” Dunn says. “It’s more focused on mathematic and rational thinking. Accessibility is really important, and humanity—it’s focusing on everyday people. It allows this new sight.”