Next week the Flannery O’Connor Childhood Home will have arguably one of the most important weeks since it re–opened.

On Wednesday, the site will be honored as host of the announcements for the National Book Award finalists. The following day, its annual Fall lecture series will kick off with a talk by Craig Amason, the Executive Director of the Andalusia Foundation, who is in charge of preserving the farm in Milledgeville where O’Connor lived and wrote from 1951 until her death in 1964.

Confronted by encroaching development and tasked with saving structures on the farm that were neglected for decades, Amason has had his work cut out for him over the nine years since the Foundation took over the property. We caught up with him by phone last week to talk about O’Connor, the farm, and the importance the property had in shaping her fiction.

What was the state of the property before the foundation stepped in?

Craig Amason: Shortly after Flannery O’Connor died in 1964, her mother Regina O’Connor left the house and lived the rest of her life in the Klein home, downtown in Milledgeville, which is where Flannery lived as a teenager. Mrs. O’Connor lived the rest of her life there. While Flannery died at the age of 39 in 1964, Mrs. O’Connor lived to be 99 and died in 1995. No one fully occupied this house, Andalusia, again after 1964. It did fall into a state of disrepair, especially the outbuildings. The main house is not in danger. Between 1995 and 1999, they did quite a bit of work on the exterior of the house. It’s in pretty decent shape, but the rest of the farm complex is in desperate need.

If the main house where she lived and worked is secure, how important is something like the Hill House (where tenant farmers lived during O’Connor’s lifetime) to future generations?

Craig Amason: It’s very important, and that’s why we’re focusing so much on the Hill House, because if we don’t focus on it, we’re gonna lose it. It’s essential to the interpretation of the farm. It’s also essential to the understanding of how significant this place was as an inspiration for O’Connor’s fiction because you have farm hands living on the farm in those stories.

It would be easy to think that raising money to preserve the legacy of one of the great American writers would be simple. Why isn’t that the case?

Craig Amason: For a couple of reasons. One is that we’re in the worst economic times of our lifetime. Plus, you’ve got tremendous amount of competition for historic preservation dollars and we live in a state where historic preservation is not a high priority, at least from the government standpoint. They just don’t have any money. We don’t restore buildings in the state, we build stadiums.

With state budgets declining for the foreseeable future, what’s the solution?

Craig Amason: I think it is continuing to raise awareness. That’s what we’ve spent a good portion of our time doing over the last 8 years. It’s paid off in the sense that our donations have gone up every year in spite of the economy. We’ve been able to restore three structures. We’ve been able to construct an interpretive nature trail and a peacock aviary.

We’ve had some successes, but we have a huge challenge. It’s very similar to the situation at Rowan Oak, which was Faulkner’s home in Oxford. For the longest time, Ole Miss had that property, but they didn’t have any money to do anything with it. It was in serious bad shape until finally people at the national level said, “For Godsakes, this is a Nobel prize winning author.” Slowly, as we raise more awareness, we’ll see more people interested in helping preserve this place.

Is that what your talk will be about?

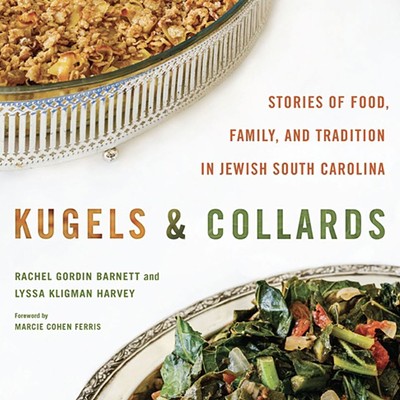

Craig Amason: I’m going to present a talk that I gave in Rome, Italy in 2009. What it does is take one of Flannery’s stories called “A View of the Woods” and talks about the events in the story and how it mirrors what was going on in Milledgeville and Baldwin County when Flannery wrote that story so far as urban encroachment and development, and the impact that had on the community and an individual family. I’m using that as a segue to talk about what we’re doing here now.

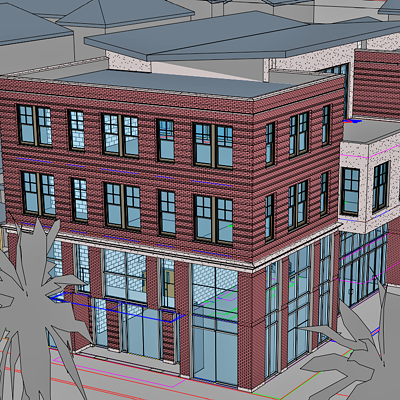

Is there threat of development encroaching on the property?

Craig Amason: I’m sitting on 524 acres and I’ve got a 20 acre complex of buildings that are falling down, after awhile you start thinking, how much of this property do I really need to have to interpret Flannery O’Connor here? We need a lot of money and we’re sitting on extremely valuable property. There’s a lot of urban development around us. There’s a Wal–Mart 1400 feet through the woods. There’s a car dealership you can hear the loud speaker from all the time. We’re surrounded by development on three sides. It’s almost like Graceland, how it used to be out in the country in Memphis and now it’s in the middle of Memphis.

She’d be rolling over in her grave if she knew you could hear a car dealership from the farm.

Craig Amason: She’s a very prophetic writer. That’s why I use this story as an analogy. When she wrote that story she knew full well what was going to happen. It was a theme O’Connor was very familiar with and something that plays out again and again in her fiction because she’s so closely related to the agrarian writers at Vanderbilt, the ones who knew how the urban landscape was going to change the culture of the South.

A View From the Woods: Preserving the Fortune of Andalusia

When: Thursday, Oct. 14, 12:30 p.m.

Where: Flannery O’Connor Childhood Home, 207 E. Charlton St.

Info: www.flanneryoconnorhome.org, (912) 233–6014

Cost: Free and open to the public