WHILE MOST AMERICANS probably can’t find Estonia on a map, the small Baltic country actually provided a stirring portrait of bravery during its occupation by the former Soviet Union.

Filmmaker Jim Tusty, whose father came to the U.S. as a child from Estonia in 1924, has made a documentary about that episode of European history, The Singing Revolution. The film’s centerpiece is a historic gathering in 1969 when thousands of Estonians at a music festival, prohibited by law from singing anything other than Soviet propaganda songs, defied the ban by singing their own traditional songs.

While both Jim and his wife Maureen are respected producers, the 96-minute The Singing Revolution represents their first feature effort. The film is inspired by the couple’s return to Estonia in the late ‘90s to teach a film course. Using very rare archival footage and interviews with key newsmakers, it’s tied together by the narration of Academy Award-winning actress Linda Hunt.

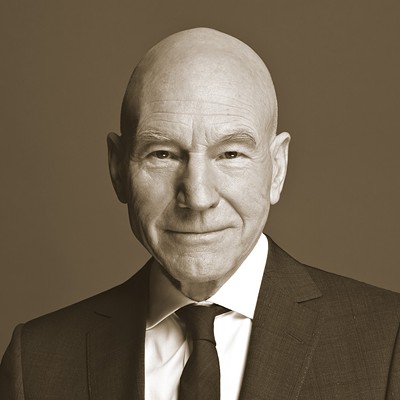

Jim Tusty spoke to us from Estonia last week.

You make the point that Estonia had the remarkably bad fortune to be conquered by two of the most heinous dictators in history: Stalin twice, with Hitler in between.

Jim Tusty: Yes, most Estonians in North America came here because they fled Stalin in 1944 when he came in the second time near the end of World War II. Stalin first came in in 1939, and destroyed a huge percentage of the population. Then Hitler came in when he betrayed Stalin in 1942-44. In that six years the country lost a quarter to a third of its population.

Most left in 1944 because they knew what living under Stalin meant. They literally fled in rowboats, at least 70,000 of them. When they got here the theory was that under the Atlantic Charter, all European borders were supposed to go back to pre-World War II borders. So everybody was thinking, great, because before World War II we had a country. So we’re all going back to Estonia in a couple of years. Well, as it turned out the end result was they had to wait literally three or four generations.

But the Estonians have never really forgotten that original intention to go home. Estoniansin the U.S. send their kids to Estonian language schools even now. They hold council meetings in the Estonian language, publish Estonian language newspapers. Their tradition has stayed extremely tight for all those years.

Describe your relationship to Estonia.

Jim Tusty: My situation is different, because my father didn’t marry an Estonian woman. He came over during the independence years. I was raised with English as a primary language. As a kid I knew where Estonia was, and I understood something about the occupation. So I was close, yet not close.

In 2001 when I was teaching filmmaking there, I first heard about “The Singing Revolution,” and I remember thinking as far as we can tell no one else knows about this. And while we all like to make fun of the American media and how poorly informed Americans are, I can tell you for a fact that no one in Western Europe has heard of the Singing Revolution either.

How were you received by the Estonians, being sort of an outsider in a way?

Jim Tusty: At first we were afraid the Estonian community would be like, “Who are you to come from 5000 miles away and try to tell us our history?” But luckily our fears were not well-founded. Estonians have pretty much told us to a person that for them it’s current events. “It’s too close to us,” they’d tell me.

See, it’s complicated because we discovered there were serious tensions among the different independence movements. It all came down to the simple question: Do you feel the Soviet Union will ever leave Estonia?

One side said, no, and there’s no way we can fight them. The Soviets had one soldier for every 12 citizens in Estonia. Therefore the best thing to do, one side said, is to work out the best deal we can. They were not communists by any means, but felt it was the practical thing to do. And they accomplished a lot, including making Estonian the official language and changing the flag. So that faction did have their victories.

But in contrast there was a radical independence movement, that would openly, verbally say the Soviet occupation is illegal. They’d say to fellow Estonians, “You’re cooperating with the people whose grandfathers killed our grandfathers.”

We showed our work edit three times privately to leaders of each of the three movements. The first two times they had lots of comments. But the third time all three said it’s fair, we can live with this.

But you say the radical movement won out despite their smaller numbers.

Jim Tusty: Yes, they only had about 1000 members at the most. One thing on their side was they had enormous connections in the United States and could raise funds there.

As we started analyzing the situation there were actually 7, 8, 9 forces for independence, but we ended up focusing on three. For example, there was a huge green movement that did a lot of environmental protesting. That doesn’t sound like a lot, but under the Soviet Union you couldn’t have any protests against anything.

Here’s the tough question: You say in the movie that Estonian independence came about through Gorbachev’s perestroika reforms. But didn’t he sort of get a raw deal? He was trying to do the right thing and the Estonians made him the bad guy.

Jim Tusty: The Gorbachev question is a profound question for me. The American perception is a little bit incomplete. The Soviet Union didn’t collapse because of Gorbachev, but despite his intentions.

You’ve got to understand his entire education was under a Stalinist system. He was a firm believer in communism. He just believed that if a human being was smart enough and given enough freedom, they couldn’t possibly adhere to anything else but communism. That’s why he was so thrown by the nationalist movements in the Baltics. He just couldn’t fathom it.

You could say he got unfairly beat up in a sense. Estonians certainly pushed the envelope for 50 years exactly as far as they could.

How would they do that?

Jim Tusty: Well, the Estonian flag is black, blue and white, and at one time you could be thrown in jail for waving it. So for example during one gathering in a square, Estonians brought out three separate flags — one black, one blue and one white. Then they slowly started moving them next to each other. It’s not exactly the flag, but it’s definitely the national colors. So everybody looked around to see if they’d get arrested for that. And they didn’t, so next time maybe they’d wave the actual flag. They kept pushing Gorbachev as far as he’d allow it.

But don’t be deceived by Gorbachev’s image. There was a massacre in Vilnius in 1991, when Russian tanks actually ran over people. But it happened on the exact day Desert Storm, so the world barely noticed. We constantly saw this pattern in Soviet history, where they’d do their bloodiest acts of state terror when the world’s attention was turned another way. They crushed the Hungarian uprising during the Suez Canal crisis, for example.

But I’m in no way comparing Gorbachev to Stalin. Gorbachev was much softer and cared more about humans. I’m just arguing against the American perception of Gorbachev as a nice guy.

Judging from the trailer the movie almost has an epic feel.

Jim Tusty: Epic is a word I’ve used. It’s the epic story of the Soviet occupation in Estonia. We cover 1939-1986 in about 25 minutes, and you absolutely need that. Then we spend the rest of the film, about 65 minutes, on the Singing Revolution itself and these amazing events. The challenge was that there’s no one Estonian leader to point to, so we couldn’t do your standard personality film. In fact the film consists of about 30 people we interviewed, but none are up there predominantly.

I’ve never seen a film where the hero is an entire country. It’s a testament to the Estonian people and how they handled themselves. Under the most dire confrontations they would remain nonviolent.

The Estonians like to say “patience is a weapon.” And I see it all the time not only in the Singing Revolution, but in business relations. They’ll wait as long as it takes to get an advantageous situation, a month, a year, ten years, whatever. They certainly have a knack for pushing the envelope as far as they can.

The Singing Revolution screens Tues. Oct. 30 at 11:30 p.m. at the Trustees Theatre and Fri. Nov. 2 at 9:30 a.m. at the Lucas Theatre.