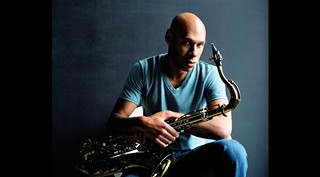

The magnificently exploratory journey of Joshua Redman’s life very nearly took a side road. If not for chance, one of the most expressive tenor saxophone players in modern jazz might today be just another attorney wearing a sharp suit in some 23rd floor office somewhere.

“I never thought I had the skill or the talent or the drive to be a good, professional jazz musician,” says the 43–year–old son of Dewey Redman, the late saxophonist for, among others, Keith Jarrett, Pat Metheny and the Ornette Coleman Group.

“I didn’t grow up with my father, but just seeing some of what he had to go through, as a great musician of the utmost integrity, the challenges he faced, I guess I had the sense that a career as a jazz musician is not an easy thing.”

In 1991, Joshua Redman graduated from Harvard University, magnum cum laude, and was accepted into the Yale School of Law. With six months to kill before the start of classes, he moved in “temporarily” with some musician friends in Brooklyn.

“And somewhere over the next six months, somehow I found myself in this place where I was playing with some of the greatest musicians around,” he says. “Both my peers, people of my generation, and some of my heroes. Older musicians, masters of the music.”

That year, he won the Thelonious Monk International Saxophone Competition, and law school faded from the picture. He was 22.

“I don’t think at the time I realized I was making a life choice,” Redman reflects. “I didn’t think I’d be sitting here over 20 years later and talking about half a life — in jazz.”

Warner Brothers Records released the Joshua Redman album in 1993. It received a Grammy nomination — no small feat for a newly–minted artist — and kick–started a career that has spanned 13 full–length albums with his band or as a duet partner, dozens of prestigious guest spots, and collaborations with the biggest seekers and innovators in modern jazz.

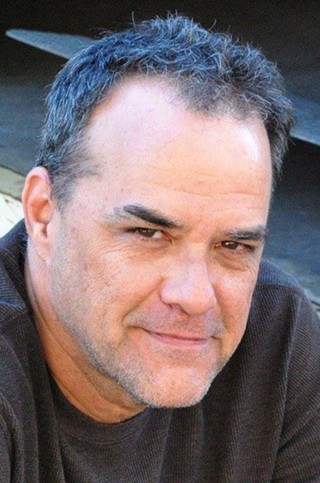

Redman makes a Savannah Music Festival appearance — his first–ever — April 6 at the Trustees Theater, alongside his professional partner in playfulness, pianist Brad Mehldau.

“I first met Brad shortly after I moved to New York, but we started playing together regularly around ’93,” Redman says. “He was in my band.

“I’ve always been a huge fan of his. He’s always just completely blown me away as a musician. I think we had a strong connection from the beginning. Over the years, we’ve played together on and off in a variety of contexts, but a few years ago we really started to re–connect. We started to play together a lot.”

Redman, like so many jazz players, has several projects going at once. He’s a member of the experimental quartet James Farm, he still plays with the Joshua Redman Trio, and a double trio, and he’s in the process of early rehearsals with a saxophone quartet.

Still, he exclaims, “It’s a great privilege to get to play with Brad so often. I think there’s a real strong musical kinship and camaraderie there, especially in this duo context. There is a lot of freedom to go in different directions, and to really live in the moment and spontaneously re–discover these songs every night.”

Starting with his 2007 Back East album, Redman has been experimenting with a different sort of trio sound: Sax, bass and drums. No piano.

Sonny Rollins was one of the most successful architects of this musical approach. Joe Henderson did it, and Ornette. Branford Marsalis has done it, too, Redman says.

“I waited some time before I started doing it,” he explains. “It is incredibly challenging. Without a dedicated harmonic instrument like the piano, there’s that much more responsibility that falls upon all of out shoulders.

“But it also can be incredibly liberating. When everything is going right, when things are on, there’s a certain kind of freedom to experience in that context, that we wouldn’t experience in a context with a dedicated harmonic instrument.”

In other words, the sax player can go charging off into left field, any time he feels like it?

“Yeah, and left field looks a little bit different when you go there,” Redman says with a laugh. “It’s maybe a different–colored grass. Because, for example if you play a melody, what might sound dissonant in the context of a clear chord underneath, might not have the same dissonance. It’s going to have a different feel. There is harmony, but the harmony is defined by two notes — whatever note I’m playing, and whatever note the bass is playing.

“Basically, it’s two moving, melodic lines that intersect to form harmony. As opposed to being a dedicated chordal instrument there, mapping out the harmony at all times.”

Yeah, and if this music thing doesn’t work out, Josh, there’s always Yale. The law never sleeps, you know.

“No, there’s enough good lawyers out there,” chuckles the veteran musician. “And bad lawyers. You don’t need another one.”

Savannah Music Festival

Joshua Redman/Brad Mehldau

8:15 p.m. April 6 at Trustees Theater