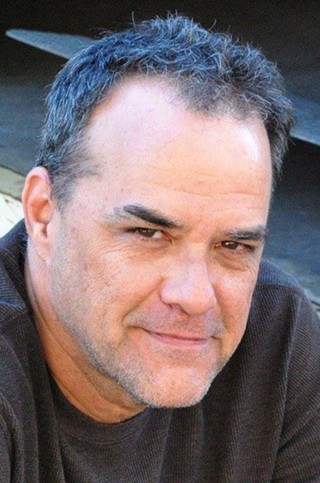

IN SAVANNAH, Gabe Reynolds puts the "play" in "play festival."

Not that he came up with the idea, mind you. The 24-Hour Play Festival debuted in New York City in 1995, and within a decade had spread like stagefire to theater groups both amateur and professional across the country.

The premise is simple: Six writers volunteer to write six brand-new short plays, with no advance notice as to what they’ll be about. At 8 p.m. on Friday night, they’re given a theme—some sort of unifying thread—and they can’t leave the theater (Muse Arts Warehouse, in our case) until they’ve completed a script.

Directors and actors are chosen early the following morning, and the shows are blocked, memorized and rehearsed. At 8 p.m. the audience comes in, and all six shows (10 minutes each) are performed.

All in 24 hours. One man’s recipe for stress-induced stroke is another man’s exhilarating adventure.

Reynolds, whose day job is as on-air talent at Rock 106.1 (under the name Kotter), is also a card-carrying member of the Odd Lot, Savannah’s hardest-working improv comedy team, has written, directed an acted in the 24PF. This time, he’ll just be observing.

It’s all very claustrophobic ... in a creative sort of way. “Watching the writers, to me, is very interesting,” Reynolds says. “The process they go through. Everybody’s got their own process. Some people seriously just shut themselves in a room, and you don’t see them for five hours. Some walk around, drink a bunch of coffee and talk to themselves. Some people bring in other people to help them type, so they can dictate.”

The “theme” is there both to provide continuity and to ensure none of the writers have brought in something previously written, Reynolds explains. “One time, they were given a picture frame and told they had to incorporate it into their show. The last one we did was around the Winter Olympics, so they needed some sort of triumphant moment in their play. We’ve given them the first line of a Shakespeare play, which had to be worked into the show. And one was, you had to have a dramatic pause halfway through your show.

“So the themes are really not going to dictate what the person has to write about. They’re free to do whatever they want, just within the little criteria that is the theme.”

Once the directors and performers arrive Saturday in the morning, no one is allowed to leave the theater until the performance ends that night.

“I love seeing it all come together,” adds Reynolds, “because there’s always that dress rehearsal where you go ‘This is not going to be ready.’ And every time, it’s come together and it’s been pretty amazing.”

The gamut is quite literally run, from comedy to drama to existentialist to science fiction. It’s like Forrest Gump’s big box o ’chocolates.

“There was one written about a man who had the most up-to-date phone,” Reynolds remembers. “It was like that Siri movie with Joaquin Phoenix, but he didn’t fall in love with the person on the other end, but it was a relationship.”

Or the touching vignette about an old couple dealing with Alzheimer’s. Or the drama set in a future when men and women automatically changed sexes.

Or this: “We had somebody write for a 10-year-old girl last year. We’d never had a kid participate in the play fest before. It was basically somebody who was overseeing purgatory, and her interaction with the adults who end up getting in a car wreck. It was written for the 10-year-old, but not played as a kid.”

Followed by this: “There was one about a guy who was at his engagement party, and desperately needed to use the restroom. But it was the women’s restroom. The scene is three ladies and him, all in stalls, and they’re having a conversation about him. The whole setup is you think the fiancée is cheating on this guy, and he’s hearing this shouted from behind the walls.

“Then at the end, you find out she wasn’t; he comes out and laughs at them all and runs out of the room. Then he has to come back in, because he didn’t get to finish what he was doing. Because he got wrapped up in the story.”

For the audience, Reynolds says, the payoff to the play-off can be exponentially huge. “They know what it is, and they’re ready to accept the process,” he believes. “They know there may be some mistakes, and it’s not going to be perfect, but I think that’s part of what they appreciate about it.”