On the west end of River Street, tourists in T-shirts and sunglasses shuffle along, snapping pictures of each other with the river as a backdrop. Huge freighters with foreign names glide under the majestic Talmadge Bridge, and on the air is a cacophony of sounds: Laughter, car horns, restaurant noise, the loud blasts of the tugboats chugging along to one tugboat task or another.

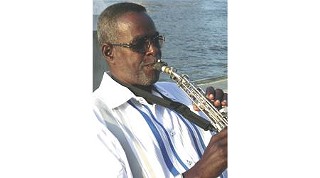

And then, there it is, a sweet, melodious soprano saxophone, wafting in and out like the unmistakable scent of something good cooking on a nearby grill. It’s “Moon River,” and it’s a thing of beauty. People stop to listen.

The man with the silver horn sits in a deck chair on the promenade, his back to the water, a tip jar at his feet. He’s Rasheed Akbar, and he’s been a street musician for half of his 57 years.

Akbar spent most of that time in New Orleans, playing for tips outside the Café Du Monde in the French Quarter, for up to 14 hours a day. In the Big Easy, he’d earned the title The Ambassador of Decatur Street.

Then came Katrina, and the virtual eradication of the only life he knew. So Rasheed Akbar, newly married, decided to start all over in his hometown, Savannah.

Six months ago, he was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver, brought on by Chronic Hepatitis C. His doctor says he won’t survive without a transplant.

“There was a time when I could miss a couple of days and the pain wouldn’t happen,” the soft-spoken Akbar says. “But now the pain just happens on its own. And it’s so strong, the pills take longer to work. I’ve been in tears a couple of times. It really wreaks havoc on me now.”

His wife, Patricia, is spearheading a donation drive to help with Rasheed’s medical bills. Local jazz musicians are planning a benefit concert, and money is being raised, bit by bit, in New Orleans.

“All the musicians I played with there for 25 years want to help and want to be involved,” he explains. “But it’s not an easy task when they’re there, and we’re here.”

As Carlton Floyd, Akbar was born in Texas on Feb. 5, 1952, but his family relocated to Savannah when he was still a baby. He embraced Islam in 1970, the year of his graduation from Beach High School, and changed his name legally a dozen years later.

He discovered his gift for music at 19, and was rarely without a sax in his hands. That sort of work was hard to find, though, and to help pay the bills he took a job as a longshoreman with the Port of Savannah.

Because his mother had relatives in New Orleans, Akbar visited every summer and grew to love the city’s unique character, and the decidedly musical atmosphere of the French Quarter. He moved there for good in 1983, and worked on the docks.

“I became a single parent, so my priorities changed,” he recalls. “I did what I had to do to maintain three kids. I was staying with my mom, fortunately – bless her soul – and eventually I got a job at the Intercontinental Hotel. And they laid me off.

“I said ‘I’m in New Orleans, man.’ I picked up my horn, and from that point on I never looked back. Music became my livelihood.”

Even though he developed a repertoire of hundreds of songs, from Coltrane to Parker, to pop standards and chestnuts from the Great American Songbook, Akbar was eager to absorb as much authentic New Orleans music as he could.

So he enrolled at Southern University and learned to sight-read. He played with dozens of brass bands and combos, all over the city, and before long was speaking the same language as his fellow jazzmen.

“Everybody knew everybody else,” he explains. “Somebody would say ‘I got these two gigs, could you take this one for me?’ I got into that environment, and cats knew I could handle it. So that put me on point with the circle of musicians that I needed to be hooked up with.”

He traveled the world as a member of the New Orleans All-Stars Brass Band.

The 1980s and ‘90s were golden. Akbar would sometimes make $300 a day on the street, and never had to look for a “real” job. “The street is where everybody got their chops together,” he says proudly. “Even Louis Armstrong did a stint there. It’s all a part of the journey in New Orleans.”

The arrival of the big casinos changed the picture. “That took a lot of the tourists away, so when they hit the French Quarter, they was just lookin.’ And the big limos would just pass by.”

Still, he survived.

When Katrina pummeled New Orleans in 2005, Akbar was in Savannah visiting his son. He and Patricia drove to Memphis to watch the TV news and wait the storm out.

“The first picture they showed on the news was the Circle Food Store,” he remembers. “The Circle Food Store was like five or six blocks from where I was staying. And when I saw that, I thought ‘New Orleans is gone.’ My whole heart just dropped.”

His house was a near-total loss, and he had the usual FEMA headaches. “The people who were stuck there all that time – I could see the despair in their eyes,” he says. “And every time I went back from that point on, I’d get the same feeling: ‘I don’t want to come back. It’s going to be too hard.’”

So in May of 2007, after finding Memphis not quite their cup of gumbo, the Akbars bought a home in Savannah. Rasheed re-acquainted himself with the top jazz players in town, including Ben Tucker, Teddy Adams and the Equinox Jazz Orchestra, and set up his tip jar on River Street.

He was delighted to discover that his old job at the port was still available – he was grandfathered in at a decent wage – and until last February, when his flu-like symptoms were diagnosed as cirrhosis, he was working the docks every day.

He’s on disability now, and his health insurance will run out in December. It’s doubtful he’ll be able to move up on the liver donor list – much less afford the procedure – before then.

On a good day, he can work for three or four hours and bring in a few bucks. Akbar hates having to sit while he plays – he likes to move and bop with the music - but he tires easily, and when the sun is bright overhead he has to strap a wide umbrella on his chair.

Still, he’s happy to be back in Savannah, which has always been – in his heart – home. “We would still have been struggling in New Orleans,” he says. “We would never be where we are now.

“We are really blessed to be here. Plus I have the opportunity to do just what I did in New Orleans. Now I’m the Chairman of River Street, because I sit in the chair! This is my new domain, and I love it.”

The Rasheed Akbar Liver Transplant Fund: http://rasheedakbarlivertransplantfund.bbnow.org/