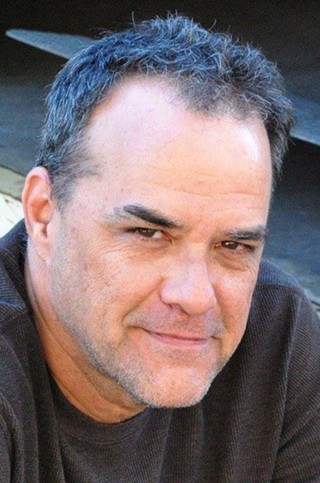

Doug Wyatt knew he was going to die.

“He went into the hospital and was diagnosed on Jan. 29,” says Gail Krueger, who was Doug’s wife for 12 years. “And he died on Feb. 9.”

The cause was glioblastoma multiforme, an aggressive and virtually inoperable form of brain cancer that is, for all intents and purposes, a death sentence.

Eighteen months earlier, Wyatt had undergone a thorough neurological exam, after experiencing a type of ambush migraine called a thunderclap.

That test showed nothing out of the ordinary, and the doctors sent him home.

This past January, however, the dark clouds rolled in. “He’d had kind of what he described as a fainting spell,” Krueger says. “He didn’t look good. He was due to go back to his regular doctor anyway, who was treating him for the flu. If you remember, at that time there was some nasty flu stuff going around.”

Still, the Wyatts weren’t overly concerned. “He was having some odd symptoms,” Krueger explains, “but every symptom kind of corresponded to potential side effects from some medication he was taking for unrelated issues.”

On the afternoon on Jan. 29, Krueger took her 54-year-old husband to St. Joseph’s Hospital, where numerous tests were conducted, including an MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging), which allows doctors to visualize the inside of the human body.

“I got him settled into his hospital room and went back to the house to pack up some clothes to bring back to him,” she explains. “And they were calling me on the phone to come back to the hospital before I even got his clothes packed.”

The tumor, it had been discovered, “was the size of his fist. I don’t know how he was functioning at all.”

Krueger is still struggling with the fact that neither she nor Wyatt saw what were – in hindsight – warning signs.

“Looking back on it, I think he had some seizures at home, that I wasn’t there to witness,” she says. “And of course he couldn’t remember, because seizures are what they are.

“You know the old saying ‘When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras’? We should have been thinking zebras.”

She was summoned to a conference room, where Wyatt’s doctor told her they’d discovered the tumor, and had scheduled a biopsy for the following Monday, four days away. There was very little chance of survival.

You don’t need to be telling me this, she replied. You need to tell Doug.

“I had the feeling they usually didn’t handle it that way,” Krueger says. “But with Doug being Doug, that’s the way I wanted it handled. I wanted him to know everything that I knew.”

Soon afterwards, he did. “He was fully aware that he had a brain tumor and that he was going to die. What he didn’t know was the time frame.”

In the end, the time frame was 11 days. He passed away three hours after going home with hospice care.

“It was kind of like a train wreck in slow motion,” Krueger sighs. “Like the worst possible combination. You know, if your loved one dies in a car accident, it’s instantaneous and you’re helpless. Or if your loved one is diagnosed with some horrible disease that you know is going to kill them, you know you have a long time to deal with it. And it’s horrible.

“I had horrible in both directions.”