WHEN I find myself in times of trouble, I’m always hoping some nice lady will come to me and whisper words of wisdom, just like in the song.

The thing is, I’m never quite sure who I’m supposed to be looking for. My idol-adverse people don’t have a go-to spiritual maternal figure, and our last visitation I’m aware of involved a burning bush.

I guess I envision the Holy Mother as a divine superheroine, an enigmatic combination of Wonder Woman and Mother Theresa, infinitely loving but not here for our self-created separations and sufferings.

Lately the picture I’ve been holding in my mind looks a lot like Mother Mathilda Beasley, Georgia’s first African-American nun and one of Savannah history’s most mysterious characters. Maybe it’s an unlikely girl crush for a Jewish mother, but ever since I read the historical marker near the Sacred Heart Catholic Church on Bull Street a few years ago, Mother Mathilda has fused into a corner of my cluttered spiritual consciousness, an esoteric place that resembles a cross between Solomon’s Temple and the Aughra’s den from The Dark Crystal.

The more I learn about this sacred sister, the more otherworldly her legend becomes. The records show that “Matilde Taylor” was born a slave in New Orleans in 1832 and arrived in Savannah as a free young woman who signed her own name as “Mathilda.”

She worked as a seamstress, operated a secret school for slave children ten years before the Civil War and married wealthy black restauranteur and landholder Abraham Beasley in 1869.

After he died in 1877 and left her a portfolio of money and property, the widow Beasley traveled to England to take the vows of the Poor Clares, a branch of the Franciscan Sisters, and returned to Savannah to found the state’s first African-American order. The newly-minted Mother Superior oversaw a school and orphanage at Sacred Heart then at St. Benedict the Moor, the city’s first black Catholic Church.

After her husband’s estate was spent, she reportedly took in sewing gigs to pay for books and clothes for her students, an early precursor to today’s educational martyrs. (Not to be confused with Susie King Taylor, another local renegade who sacrificed much to teach African American children both in secret and in the open.)

It’s humbling and inspirational to learn that Mother Mathilda devoted her fortune and the rest of her life in service to her students. But it’s the description of her death that puts my reverential imagination over the edge: On Dec. 20, 1903, parishioners entered her cottage to find her body in repose in front of her private altar, hands clasped and arms outstretched in prayer.

Her funereal instructions and burial garments were folded neatly beside her, giving the scene an eerie yet holy prescience. Even now it gives me goosebumps.

Mother Mathilda’s whole tale seems to transcend history into legend, and so many questions remain about this mythical mystic: How did she escape slavery? Where did she learn to read and write? Why did this “commanding figure” of “extreme height” risk fines and public lashing to share knowledge—and therefore power—in one of the South’s most stubbornly segregated strongholds? What were her thoughts in those last moments before her spirit rose from the earthly plane?

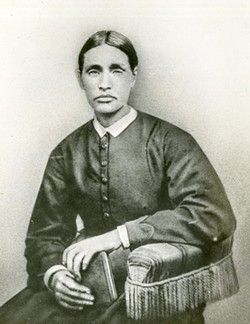

Her enduring enigma is fed by two photos that supposedly depict Mother Mathilda Beasley: One is a portrait of an ethnically ambiguous face with striking cheekbones and hypnotic eyes; the other features an elegantly dressed, young African-American woman posed with a parasol.

Though they have been used interchangeably in stories about Mother Mathilda, they are clearly not the same person. (Artist Michael Porten solved this conundrum by presenting her likeness in bas relief profile as part of SCAD’s Women of Vision installation in Arnold Hall.)

I consulted Georgia Historical Society archivist Katherine Rapkin to find the angel in the details: The first photograph is undated, part of the vast Walter Charlton Hartridge Collection documenting two centuries of Savannah history.

The latter is from the Georgia Historical Society Collection of Photographs, and Katherine notes that specific details of the dress place it taken in 1890, when Mother Mathilda would have been almost 60. It seems pretty unlikely that she would have looked that fantastic at that age, unless the nuns made a secret beauty product out of saintly relics that we don’t know about.

More reasonable is that this lovely lady is Josephine Beasley, wife of the younger Abraham Beasley and Mother Mathilda’s step-daughter-in-law. (Abraham Sr. had a son from a previous marriage, and while she was a maternal figure to many, Mother Mathilda never bore kids of her own.)

Added confirmation comes from a corresponding portrait of Abraham Beasley, Jr. in the same collection.

“It’s possible that Josephine has been mistaken for Mathilda because Abraham shared the same name as his father and people presumed the couple to be the elder Beasleys,” explains the archivist of the confusion, adding that “confirming identity of people in photographs from the 19th century presents challenges because in many instances there may be no other representative depiction for comparison.”

I’m going with the first one because the features seem to align more with her obituary, which notes her lineage as French-Creole and Native American. Plus the expression on her face is righteously beatific while conveying the weariness recognized by every mother who is pretty dang tired of trying to take care of all y’all.

Both images appear in a fascinating installation at Mother Mathilda Park on East Broad Street, where her tiny cottage was lovingly restored and relocated in 2014 and currently maintained by Chatham County Parks & Recreation. The agency recently hosted a birthday celebration outside the cottage, the start of a campaign to raise Mother Mathilda’s profile. CCPR Director Steve Proper has reached out to tour guides to include the site and hopes to increase the hours at the cottage in 2018. (It’s currently open Wednesdays from 11am to 1pm and Saturdays from 10am to 3pm.)

“We want to re-introduce Mother Beasley to the Savannah community and its visitors,” said Proper as kindergarteners from nearby East Broad School listened intently to her story. “She was a very special person and important figure in the city’s history.”

I can’t think of a more appropriate icon to ascend to a higher place in the metanarrative, a reminder that we can affect change while comporting ourselves with dignity and grace. I admit that I was hoping for some kind of divine visitation as I stood in her modest rooms, imagining her laying prostrate on the wooden floor, caught between heaven and earth.

Instead I could only think about the challenges of the world and all the broken-hearted people in it, doing their best to keep the faith in the face of violence, sickness, fire and war. I realized that there’s no wisdom in waiting around for the answers, which have always come from real human beings who use their time here to figure out how to help.

Yet a few days later as I was worrying over my personal problems and walking the dogs around her gorgeous park, I do believe Mother Mathilda came to me.

Nah, not a angelic vision or a tall, austere woman with piercing eyes. Just a breeze rustling the oaks and a trace of a thought:

Do the work set before us as best we can, and let the rest be.