IF YOU’RE searching for a romance that beat the odds, consider the story of C.S. Lewis and Joy Davidman.

They were both writers, but the comparisons ended there. His Christian faith warred with her atheism; she was a fiery New Yorker who was married with two children, and he was an Oxford and Cambridge scholar who never left Britain.

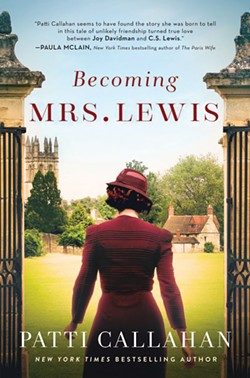

Yet, they fell in love, and Patti Callahan Henry’s “Becoming Mrs. Lewis” lays the story out for us.

Callahan Henry, a New York Times bestselling author of twelve novels, is set to appear at the Savannah Book Festival on Feb. 16. We spoke to the Birmingham- and Bluffton-based author, publishing under Patti Callahan, last week.

I’ve always felt that C.S. Lewis was an author I couldn’t confine to any sort of genre, and because of that I didn’t know much about him.

That’s part of why I wrote the book. What we do know is a lot of myth and conjecture and guessing. We know C.S. Lewis as the guy who wrote Narnia or “The Screwtape Letters.” But even more fascinating was the fact that people knew so little about his wife, who, if people know anything about her at all, it’s that she’s the dying wife of C.S. Lewis. When she died, she so broke C.S. Lewis’ heart that he wrote “A Grief Observed” [under the pseudonym N.W. Clark]. It’s one of the best books on grief ever written; it’s the seminal book on grieving and the things we go through. In it, he goes through doubt and faith—it’s a heartbreaking book. And he wrote it about her.

It started to fascinate me that the only thing anyone ever knew [about her] was that she broke his heart. She is this fiery, brilliant woman. When I did my research, I realized there were two Joy Davidmans. The first was this New York raised, assertive, married with two kids woman who inserted herself into C.S. Lewis’ life. Then the second was this fiery brilliant woman who so enchanted him that he said she was not only the first woman, but the first person, who was as smart as him. Their improbable love story totally fascinated me. When I first learned about her, I thought she was this hybrid woman. She was this New York, Jewish heritage woman born in the Bronx who was an award-winning poet and a novelist—but she was also married with two kids, and an atheist and a communist.

On the other side of the ocean—and keep in mind this is the late 1940s, we’re not emailing—you have this Oxford don, never left Ireland or England except for six months when he was in the war. And he’s 17 years older than her. It’s the most improbable love story ever. How are they ever going to meet? How are they going to become friends? Fall in love, forget about it. Get married? No way! He’s this staunch Anglican man who would never marry a divorced woman. I wanted to know what happened, so I wrote about her.

What did you find?

Falling in love with and marrying C.S. Lewis was only one of many fascinating things about her. She was a woman ahead of her time, forging these trails. As I did my research I found this quote by her: “If we should ever grow brave, what on earth would become of us?”

She wrote that question and kind of buried it in this essay called “On Fear.” I never heard anyone pull it out. What does that mean? What is the answer? I looked in the essay for the answer and I never found it. I realized that she answered that question with her life. She is constantly a new wonder to me, even after the book.

How long did the writing process take, from deciding you would write about her to finishing the book?

I first learned of her twenty years ago, but from the time I first said I was going to write about her, it was about three years. It was a slow burn. I didn’t even know I wanted to write about her for a long time. It was something that came to me when I was in a stuck place. I was talking to a girlfriend of mine, who’s also a writer, and she said, “What would you write about if you could write about anything you wanted?”

That is such an excellent question.

What’s even more astounding is that it was hidden down there. She asked just the right question at the right time.

You said that much of what we know about both Lewis and Davidman was conjecture. With that in mind, was there much source material out there for you to use?

There is so much out there. Because she was such a prolific, famous writer in her day—and, of course, he was too—I had loads and loads of what we would call primary material. There were essays, novels, letters. That’s good and bad because I wanted to be true to her, and yet it was like I was drinking out of a firehose. I had to really narrow it down. What did I want to know? How much did I want to know?

What was the writing process like after that?

You start to see connections nobody had seen before, the scenes of her life that would tell the truth. I spent a long time building what I called the skeleton because I wanted the skeleton to be 100 per cent facts. You can’t make up things [about their life]—they are both very well-known. I took liberty within constraint. It was the most fun I’ve had writing a book, ever, and also the hardest.