HISTORY, especially in Savannah, is immediately visible and intrinsically hidden. Historical architecture and styling paints a scene across time, yet those signifiers distance us from the human realities we share with our ancestors.

Whitfield Lovell’s work breaches this divide, delving into the lives of African Americans that lived between the Emancipation Proclamation and the Civil Rights Movement.

This Thursday at the Jepson Center, Telfair Museums unveils “Deep River,” an exhibition of Lovell’s work, featuring an installation, drawings, and tableaux works.

Touching on themes of passage, memory, and freedom, his work has been included in exhibitions at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, among others.

In 2007, Lovell was named a MacArthur Fellow—a prestigious distinction, commonly called a ‘“genius grant.”

He places us face-to-face with dignified yet ordinary African Americans. The anonymous portraits are primarily sourced from studio photographs.

“They have a certain beauty to them. They were being captured in the way they wanted to be, at a time that they wanted to be captured,” Lovell tells Connect.

Exquisitely rendered at life-size in black and white on found materials, like wooden fences, the faces have soul and narrative embedded in their gazes.

The work is seductive—nostalgic yet gritty. Antique objects mingle with the figures.

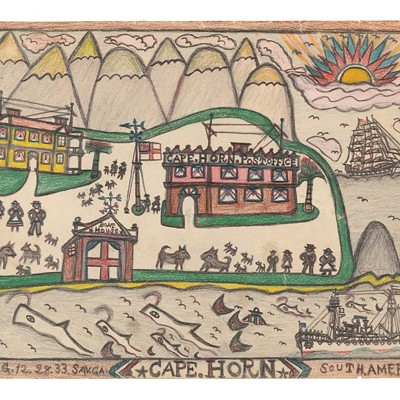

In one tableau, “Pago Pago,” Billie Holiday’s voice seeps from stacks of vintage radios sitting below a drawing of a WWII soldier.

Time and history flow through the work.

“I have an odd relationship with time,” he says. “1924 to me is like yesterday. It doesn’t go away and it doesn’t get weaker or less relevant because more time has passed by.”

Perhaps, Lovell’s impression of time can be traced to his strong sense of family and its connection to the larger cultural narrative.

Raised in the Bronx by parents whose families settled in New York City—his father’s from Barbados and his mother’s from the South— the story of the Great Migration was central to Lovell’s life.

“We were first and second generation New Yorkers, so that meant that we really were raised by people who were from somewhere else and had a lot values and cultural issues from other places,” he says.

From his mother’s parents he received “a strong sense of ancestor worship” and a love of antiques. Throughout our talk, Lovell falls into personal stories; chats with grandparents and childhood visits with family in South Carolina. For him, these experiences were as much about the present as the past.

Civil War-era Contraband Camps established throughout the Southern states inspired the “Deep River” installation.

“The camp was a Union campground which offered a safe haven to runaway slaves. It gave them asylum and shielded them from being recaptured and returned to their owners,” Lovell says.

“The idea of there being a place one could go to seek freedom was very haunting to me. What would provoke someone to leave everything they know, to travel to an unknown place, not knowing what lies ahead, and face many dangers? Because what was on the other side of the journey was worth the danger.”

“‘Deep River” is a departure for Lovell. The work sets a stark stage, integrating new media with the antiquated.

Video of a flowing river is projected on the walls and sounds of birds, wind, and the river surround the audience.

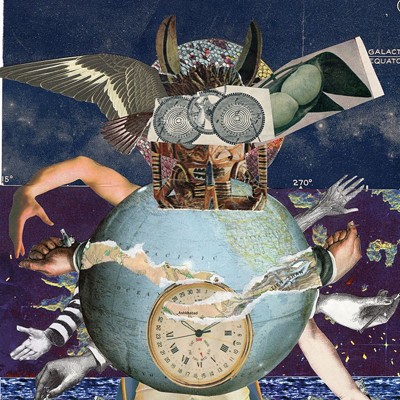

The focal point, a mound of dirt strewn with personal belongs, is in one sense macabre. Surrounded by portraits on wooden discs, symbolically resembling headstones, the mound can be seen as a burial ground.

Yet the dirt transcends this dark reading and simply becomes what it is— earth. It can symbolize a riverbank, a campsite, or the ground traversed to reach that land. It is a marker of a forgotten geography, story, and people.

Lovell’s “Kin” series, also on display, marks another progression in his work.

“I started looking for images that were not these lovely, soft photo studio images but photo IDs, mug shots, pictures that were taken not so much for posterity or to send to someone. They were taken because you had to identify yourself,” Lovell says.

The portraits on paper are paired with objects in shadow boxes. To marry the images, he uses intuition to consider the visual, emotional, and symbolic resonance.

“The choice of objects is the most exciting part. When I find the right image to pair up with a head and it clicks, it’s just euphoric. Sometimes the images bring up very poetic, metaphoric connotations; sometimes political, sometimes tragic, sometimes light and humorous, sometimes loving and tender.”

Together, his works bring light to generations of everyday people, stuck in a limbo between freedom and enslavement, yet striving and building better lives for their families. It highlights both the profound and the mundane in their lives.

“They were not honored. They were not acknowledged. The work is certainly examining history and calling on people to contemplate that time period and those beings. Raising the consciousness of who they were,” Lovell says.

While the tension of the historical period informs the work, the story he finds most compelling is “the beauty and the humanity of the people who went through it.

By looking to the core of what makes us human, Lovell crafts a timeless connection that speaks to a modern audience on a personal level, entrenching us in our own humanity while reminding us of our innate bond to the past.