HOW MUCH of our identity is formed by our family?

Bridget Conn sought to answer that question through her work in “All Hexed Up.”

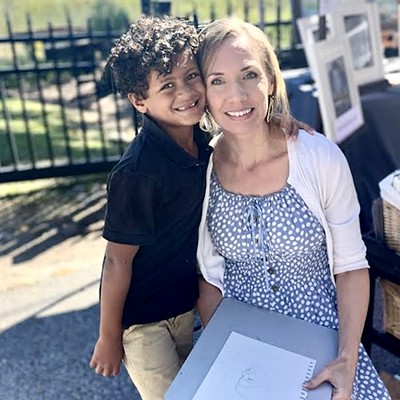

Conn, a photography professor at Georgia Southern’s Armstrong campus, grew up with a tenuous grasp on her family.

“I didn’t know my dad’s side of the family at all,” she recalls. “Nobody talked about stories, so my connection to my family was really cut off. I started realizing in my early twenties that I had a lot of different experiences than other people.”

The main tradition Conn clung to was her family’s morning tea.

“Every morning, we drank tea,” she says. “I remember my grandmother making me tea in the morning and I could hear the clink of the spoon and the cup. It was just something that I felt some sense of identity with.”

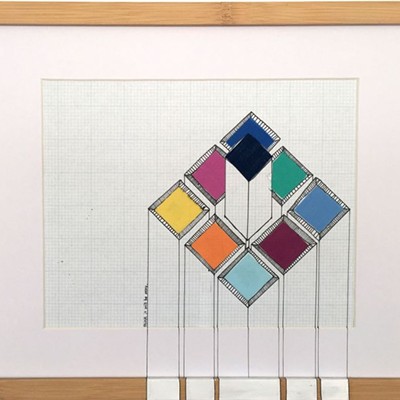

Conn saved each tea bag she used in the morning to create works like “Quiet.” After discarding the grinds and unfolding the paper, she went into Photoshop and gridded off a photograph, printing part of the image onto each individual tea bag.

“After that, it’s a lot of painting,” she notes. “They come out looking like a blob—all the color in there, every little bit, I painted by hand.”

The bird in “Quiet,” a cedar waxwing, also holds metaphoric value.

“It’s my favorite bird,” Conn enthuses. “When I was getting into learning about the environment, I also got into birding. I wanted to see one for years and I never did. Finally I was in Asheville and I put it all together that they stay high up in the trees. They had been there all along. When I heard their calls, I was like, ‘Oh, I’ve known this for years! What if I had just paid attention?’”

Since Conn’s closest tie to her family was through her mother’s side, she felt affinity to the women of her family.

“Even though I couldn’t identify who those women were by name, maybe I could have some sort of relationship to the idea of what women of those past generations were, like their roles in society,” Conn explains. “Then I was introduced more to this idea of third-wave feminism that you could go back and embrace these activities that were deemed women’s work and had such a negative connotation.”

Specifically, Conn discovered the familial link through cooking.

“There’s a powerful knowledge in that, ‘oh, I baked this from scratch.’ I just kind of grew that sense of identity out of that,” she says.

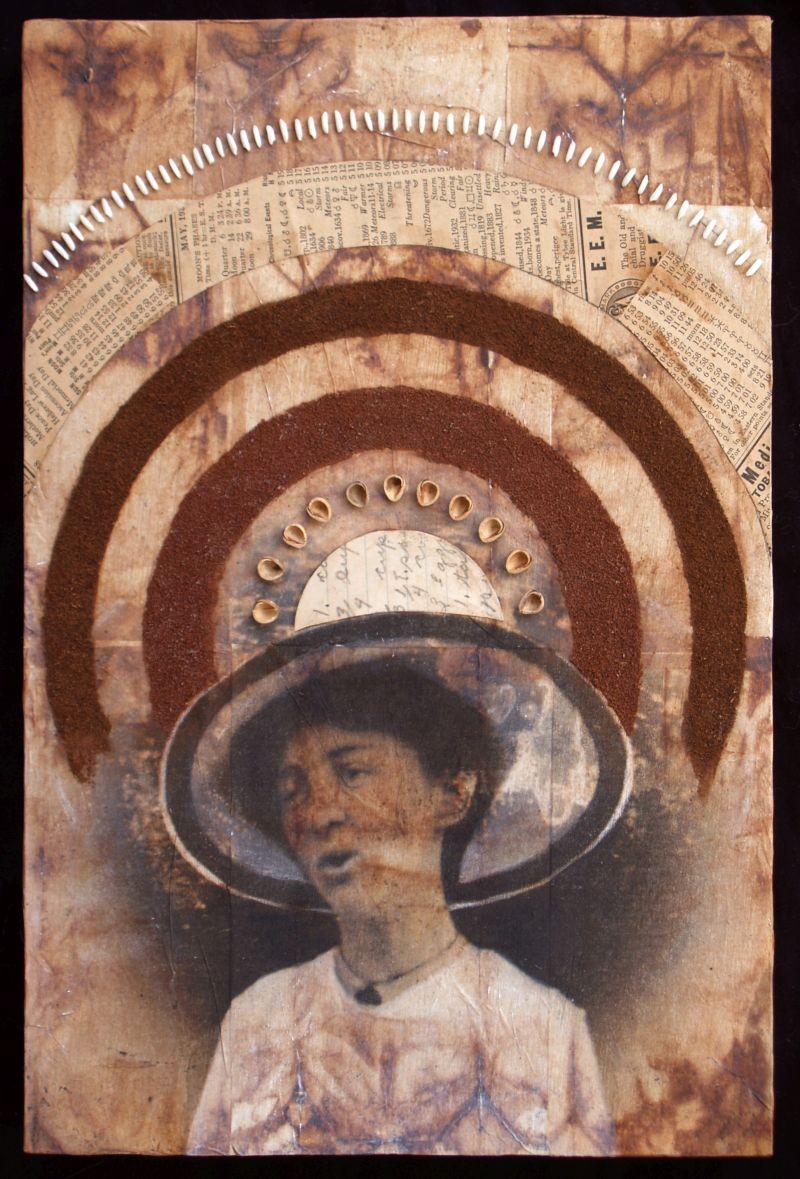

In “All She Knew,” Conn uses spices and cutouts from a recipe card along with a found photograph she discovered in grad school. The negatives dated back to the early 20th century, and Conn latched on.

“Working through all those issues of identity, I didn’t have photos like that of my own family, so I adopted these negatives, in a sense,” she says.

This body of work came to a close because Conn’s search for identity also closed when she met her father’s side of the family.

“I had met [my father] a couple times when I was younger, but it was the bigger family on my dad’s side that reached out to me,” she explained.

“It took several years, but I hit a stopping point with this work. I felt I didn’t need to work through it anymore. It was terrifying! But the work I’m doing now is all experimental dark room [photography] stuff. The work in this show spans from 2003 to 2015. It’s a good long continuum of it all.”