SARAH MABRY likes her work pretty and creepy.

“They’re very ominous,” she says. “It’s all these bright colors, but it’s a little grotesque. I love walking that line on the border of really nasty but kind of cute, too.”

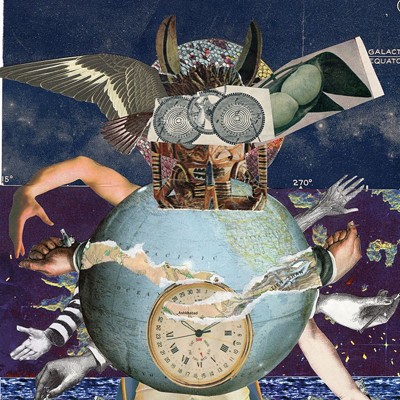

At first look, her body of work in “I Don’t Mind” is harmless enough. The paintings are abstract patterns done with paint so bright it almost glows.

But that’s not nearly all “I Don’t Mind” is about.

“About two years ago, I lost my dad to leukemia, and that’s where the whole thing comes from,” remembers Mabry. “So many of my family members have had cancer or other illnesses. Each piece in the show has a different cellular structure of the disease I lost a family member from.”

Mabry prints the structures onto a 36”x36” wood panel and either digitally manipulates or paints them.

“You can see the structures enough where, if you know what they are, you can see them, but if they’re far enough away, it just looks like an abstract painting,” says Mabry. “The whole metaphor is about covering up with false positivity. That’s how everyone handles things.”

The bright paint serves as a metaphor for the bright faces put on during the grieving process.

“I’ve been doing a lot with how people handle grief and how it affects your mental health,” explains Mabry. “I use a lot of bright colors as a metaphor towards false positivity. They’re really bright, grotesque colors. Hot pink is fun, but it’s artificial and in-your-face. I’ve been using that a lot.”

The end result is a sadly beautiful body of work.

“They’re actually really beautiful, which I thought was kind of insane,” laughs Mabry, “because [disease] is such an ugly thing, and it’s a mutant cell with all these different variables added into the normal cells. It really depends on which part of the body you’re looking at—you get some really awesome imagery out of it.”

Following the grotesque theme, Mabry also created for the show three-dimensional pieces that resemble skin being pulled apart by carabiners.

“I didn’t realize I enjoyed [grotesque art] until I started using a lot of fiberglass and I was covering inflatable things with it,” recalls Mabry. “I have this inflatable duck I covered in fiberglass, and then I popped the duck and pulled it out. It looks like a flake of dead skin, but the eyes stayed there. My professor was like, ‘This is super gross. Do it.’ If it makes me uncomfortable, that means it’s kind of interesting, and you never know if you hate something until you actually do it.”

That attitude has carried with Mabry through her whole artistic career. When she first came to SCAD, she was interested in photorealism, which quickly fell by the wayside.

“I think everyone is,” she says. “Then they take abstract media and they don’t want to do photorealism anymore—there’s something a little more fun. It was just like, ‘Oh, I can paint a bowl now.’ I didn’t know at the time what I wanted to paint, and I got kind of an empty happiness from it. But once you get in your concepts and strategies classes, you get to fly up on your own.”

Mabry flew towards the abstract style she now uses in the series, and it’s paid off.

“You never really know what’s going to happen in life,” Mabry muses. “[Art] is such a big part of your life, if you’re really passionate about it and it’s how you deal with things. I couldn’t imagine not [making art] forever. I was so terrified that if I went into the museum field, I’d become one of those people who didn’t make art, like an office lady. But it’s a commitment you have to make to yourself.”

Mabry has been working at Sulfur Studios since September, which inspired her to consider museum or gallery jobs when she graduates in the summer.

“It’s a whole other world, a whole different way of thinking about art,” says Mabry. “It’s not just about what the work is about, but about how it looks in the space. I think from working there and dealing with shows, I look at gallery spaces so much differently now. I now think, ‘How would this work a little better?’ I see where things get too clustered together.”

Mabry takes a different approach to her creative process.

“I feel like I make my worst art when I think about it too much,” she admits. “One of my professors gave me the best advice—and people always laugh because it makes no sense—but he said, ‘Care less about what you’re doing.’ It sounds stupid, but I remember my very first class in painting. I was taking an oil-based media class and probably spent 30 hours altogether on this one painting of a bowl. You don’t want to be there, you hate it, and it ends up in your mom’s basement. When you make something that’s genuine, it reads better because you’re not thinking about the technicality of it.”

Overall, “I Don’t Mind” is a deeply personal yet relatable show.

“I guess the main thing is that the work is about my life,” says Mabry. “It’s about how I’ve dealt with things. Each piece does feel really personal to me because there’s a specific person that it’s about. But it’s also about my family, it’s about the people who have had these illnesses before. I think that’s what makes it really relatable to other people. I’m not the only one who’s had a parent pass away from cancer, or a family member have a liver disease, or something like that.

“It’s a metaphor for you’re acting like everything is good, but it’s all falling apart.”