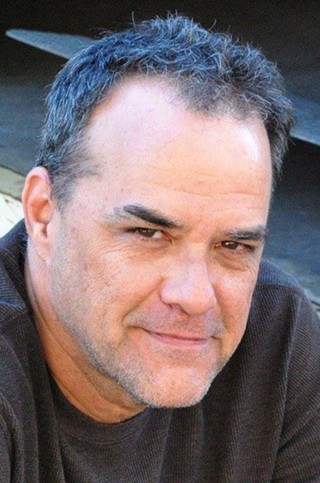

Since his breakout role on HBO’s Six Feet Under, Ben Foster has appeared in one high–profile feature film after another. He played the mutant Angel in X–Men: The Last Stand, drug–addled teen Jake Mazursky in the crime drama Alpha Dog, and psychotic cowboy Charlie Prince in the western remake 3:10 to Yuma.

Foster’s new film is The Messenger, in which he and Woody Harrelson are emotionally scarred veterans of the Iraq war, assigned “the worst job in the Army” Stateside — notifying family members that a loved one has been killed overseas.

Against orders and against logic, Foster’s character falls for a young widow, played by Samantha Morton.

Foster, Harrelson and writer/director Oren Moverman will attend Saturday’s screening of The Messenger at the Trustees Theater; afterwards, both actors will receive awards from the Savannah Film Festival.

The Messenger — the first film to put Foster’s name not only above the title, but above those of his co–stars — has been getting rave reviews. There’s talk of an Oscar nomination for Foster.

At 29, Foster has more good notices under his belt that many film actors twice his age. He is known for his piercing eyes and quiet intensity — and his ability to deliver the goods, even when the film itself is substandard (see the recent Pandorum).

It occurred to me that Jake Mazursky in Alpha Dog and Charlie Prince in 3:10 to Yuma are like different generations of the same character. Do you ever worry you’re getting typecast as the intense, crazy guy?

Ben Foster: I’m sure on some level some psychologist could have a field day with me on the roles that I end up doing. It’s really project to project, and where I’m at and who I get to play with.

You left Iowa at 16 and went to L.A., and started working almost immediately. Do you ever pinch yourself?

Ben Foster: Oh certainly, every day. I was talking to my mom about this very thing not a few days ago. I’m incredibly lucky. There are so many gifted people who aren’t at the right place at the right time, for whatever reason. That’s not to say it’s been an easy road. And at the end of it, hopefully, I’ll be able to keep playing.

What do you look for in a role?

Ben Foster: It really depends on where you’re at. This idea of only doing projects that speak to the deepest corners of your inner core, that’s somewhat laughable to say these days, and where this industry is at. That being said, I’m not going to choose a job and spent two or four months of my life with strangers making something if I didn’t believe that we could create something collectively that was exciting. Sometimes it turns out really well, and other times... there are limitations. Creative limitations, financial limitations, time.

Do you ever realize this while the film is in production — “This one’s not going to be so great, but I’ve committed” — or do you always have to believe it’s going to be a great movie?

Ben Foster: I gotta go in thinking that each one’s going to be special. It doesn’t have to be the greatest film of all time, but if you don’t have that belief... you know, only you can blow your own candle out. And it adds up if you’re doing things that you don’t believe in. If you’re approaching a role as an actor approaching a role, there’s too much distance. It doesn’t feel good, and people don’t respond to it, and it’s just not worth the time. Sometimes, it works out well.

You recently co–starred with Dennis Quaid in Pandorum. The reviews were... well, not good. What were you thinking as you read the script?

Ben Foster: It was a fairly innocent read. It held my attention. I was very apprehensive about doing it, but I spoke with Christian Alvart, the director, and he had a very specific idea of how he wanted to shoot it... I turned it down again.

I think they came back to me three times, and I guess like I felt I was taking myself too seriously and thought “I’d certainly like to go to the movies and be entertained.” I hadn’t done a proper sci–fi picture before, so I gave it a shot.

You played astronauts in a broken spacecraft. What was shooting that like?

Ben Foster: It didn’t turn out — in the experience, nor in the final product — the way that it was presented to me. And that’s fairly frustrating.

How did you approach The Messenger?

Ben Foster: The Messenger has certainly been a labor of love. I’m pretty press–shy, but for The Messenger I’m going on a full tour, and that’s not limited to the fact that I’m just proud of the film as a whole; more importantly, I’m proud of the questions it asks.

I was drawn to it initially because of Oren. It was the only script that dealt with the war, that I had read, that presented the results of warfare without taking an overtly political side. To get lost in that world... it’s having the opportunity to learn things that I don’t know about. I’ve had friends in the military, but the opportunity to spend time with vets, and the soldiers that have come back, it was truly a life–changing experience.

We went to Walter Reed Hospital and spent time in the amputee ward. The head of Casualty Notification for the United States was on set with us every day. I wouldn’t say it was an easy shoot, but the space that Oren created and the resources for research, allowed us all to get lost. And getting to work with Woody Harrelson, who I think handed in one of his finest performances. Harrelson is my brother. I’d do anything for that man!

And Samantha Morton and Jenna Malone... I can’t imagine that anyone gets an opportunity to do too many that stick with you to this degree.

Do you go looking for fresh challenges?

Ben Foster: I guess the challenge is: I’m beyond compelled to put myself in a situation where I could experience something that ordinarily I wouldn’t have the opportunity to. So yes, it’s exciting. It’s mostly exciting to work with people who give a shit.

You practice transcendental meditation. What does TM do for you?

Ben Foster: It’s a technique, twice a day. It’s not a religious or even a dogmatic technique, it’s an ancient, simple, quiet, internal technology that you do with yourself. It’s basically gettin’ rid of the static. It’s tuning, you know?

It’s not as simple as just saying “clearing your head.” It’s a rooting and a tuning, if that makes any sense.

There’s just so much input in the world, and we absorb this. And our families, and our work, there’s so many demands. And what this does, it’s a reset button. So it allows me more energy, when I take 30–45 minutes in the morning.

Yeah, it’s a pain in the ass on set. If my call time’s 5 in the morning, I gotta get up at 4. But what it gives me during the day is just a resource of energy, and the ability to hear what I’m actually thinking, rather than spitting back what I’ve been told.

It’s up to you how you use it. It’s like eating well and getting a good night’s sleep: You’re going to perform better — whatever action you’re doing, with friends of family, or your job or on your own. It’s just a stabilizing resource of energy, and clarity of thought.

What’s next for you?

Ben Foster: I just finished shooting a film in Armenia called Hear — it’s kind of a meditative road movie. And now I’m on my way to New Orleans to shoot some guns with Jason Statham. It’s a remake of the Charles Bronson movie The Mechanic. cs

Savannah Film Festival: The Messenger screening

Where: Trustees Theater, 216 E. Broughton St.

When: At 7:30 p.m. Saturday, Oct. 31

Tickets: $5–$10, at (912) 525–5050

Woody Harrelson and Ben Foster Tribute accompanies the screening