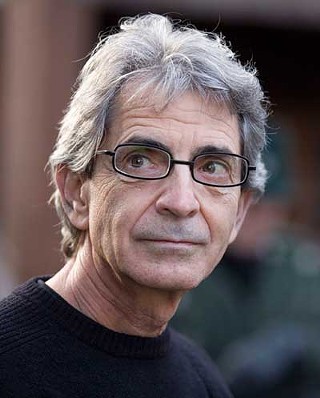

Michael Fink is an Academy Award-winning visual effects supervisor whose career spans 34 years of movies you’ve seen. And enjoyed (well, some of them, at least).

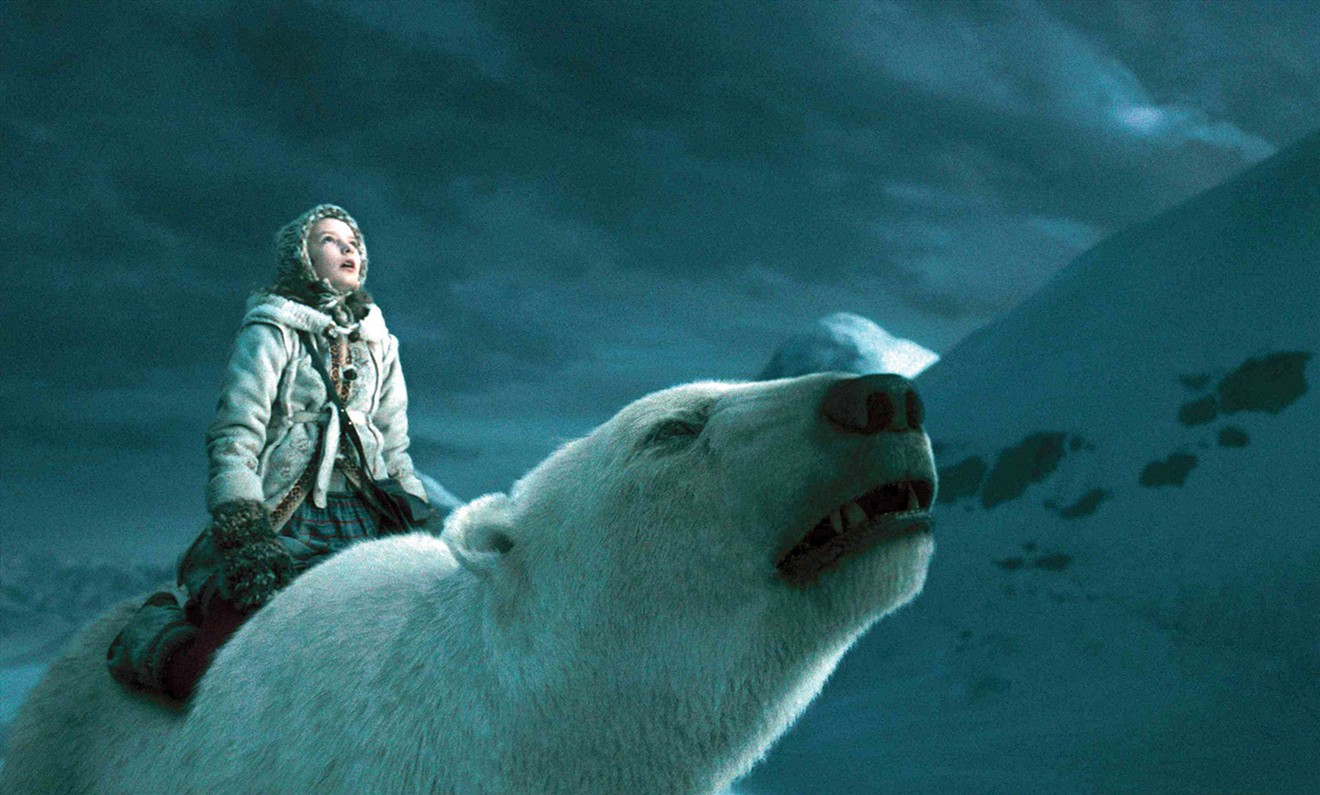

Here’s a partial filmography: Avatar; Contact; X-Men; X2; Constantine; Braveheart; Mars Attacks!; Tron Legacy; The Golden Compass (that’s the one he won the Oscar for); Eraser; Thirteen Ghosts; The Tree of Life; Tropic Thunder, Moonlight Mile; Road to Perdition; Batman Returns; Batman & Robin.

Fink also undertook considerable work on the animal effects for Ang Li’s stunning Life Of Pi – although, he is quick to point out, Bill Westenhofer was the senior effects guy on that film, and took home a well-deserved Academy Award.

He is at the front rank of filmmaking artists whose constant quest for improvement – via giant strides or baby steps – has made the cinematic union of art and technology something seamless and golden and universally appreciated.

Fink, who teaches at the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts, will be at Gustein Gallery Wednesday afternoon (Oct. 30), part of an industry panel called The Art of 3-D.

I don’t like having to put on those stupid glasses. Is 3-D really the future of filmmaking?

Michael Fink: No. Here’s what I think: I love 3-D movies. When they’re well done, I really love them because I don’t notice the 3-D. If it’s well enough integrated into the story, and into the purpose of the filmmakers. And you can see that in films like Life of Pi or, more recently, in Gravity. You really get, I think, an enhanced storytelling. And that’s really what it’s all about. So do we need it? No, we don’t need color either – you could make all movies in black and white, why do we need color? And we could just paint frames on the wall and have people walk around, just as they did in the Renaissance looking at frescos on church walls. And see the entire story of the Bible played out on the walls of the churches. So nobody NEEDS any of this stuff. And the future of filmmaking doesn’t depend on it. I think there are aspects of filmmaking that are really interesting and intriguing. I think the immersive technologies are only now just beginning to be tapped. The problem for me is that a lot of the immersive technologies that rely on 3-D displays and 3-D technology is that they’re isolating, and that they tend to be single-viewer experiences. And the whole thing about watching a film is you go to this theater and you have this communal experience. Which people are not necessarily conscious of, but they feel it. You mentioned you don’t like those glasses … I don’t know anybody that does! I’ve never walked into a 3-D movie and said “Man, I can’t wait to put on those glasses!” It’s a step toward that terribly immersive stuff where you’re the single viewer. In Gravity, the sense of being weightless, and the sense of being adrift, was so enhanced by making that a 3-D movie. I think it was totally the right choice. Is it the right choice for every movie? No. Some movies, there’s no need.

The technology is changing so quickly. Were there things in, say, your work on Life of Pi, that could not have been dreamed of 10 years ago? Is it improving that fast?

Michael Fink: Yes! What’s really helped all of this along is this rather massive increase in computing power, and the ability of networks to shuffle data back and forth. I know it sounds funny, but what made Life of Pi possible was what we call Pipeline, which is the ability to manage huge amounts of data, and keep it in synch and correlated, so that when you render a frame, all the right hairs are in the right place, and the right shadows, and the right highlights, the right dynamics, the right muscles, the right skin, the right background and the right lighting … we’re making pictures out of Ones and Zeroes. We have two electrical states, On and Off. And out of On and Off we make pictures, like the whale turning into the animals that I did in Life of Pi, or the tiger, or any of these other things. Actually, my favorite animal in Life of Pi is the orangutan.

So as much people talk about “Well, you just press a button and ….” No. It’s really hard work. And every day there are new tools.

The evolution of visual effects has a lot to do with the story. When Jim Cameron wrote The Abyss, and needed the psuedopod, nobody was thinking the psuedopod was going to be a computer graphic … nobody really knew how to do it. It was that story element, and the requirement of that character in that movie, that drove that character to be done in computer graphics. And that was absolute groundbreaking work. Nothing had ever been done like that before.

Your background was as a visual artist. Does one need that eye, and that sense of composition, to move into filmmaking visuals? In other words, do you have an artist’s eye, or a technical eye?

Michael Fink: You need both, I think, and you need the ability to imagine what that frame might look like – but literally simultaneously you’re thinking, in the back of your head, what are those elements? How do you build that?

Building a visual effects shot is not much different than building a house. You need a good foundation, you need walls, you need to decide what color the walls are, whether you’re going to have brick on the outside or painted wood. Once you’ve figured out what you want to see, then you start breaking it down into its constituent parts.

And once you do that, you find out “it’s not really as difficult as you thought it was, but we don’t have a tool for THIS. And we don’t have software that’s going to help us do THAT.”

When I started The Golden Compass, and we were doing the bears, I said “We have to develop dynamic grooming software for the bear fur.” Because the bears in The Golden Compass wore armor. The armor would push the fur down, as it rode on the fur - depending on what the bear was doing, that fur would either get pushed down or not. We had to create software which hadn’t really been done yet, to make sure that the armor looked like it really was riding on the bear, but it wasn’t glued to the bear. It wasn’t just stuck there. The bear would have to move underneath it just right. You don’t want it to look like it’s just floating on the bear, but you also don’t want to it to look like it’s stuck to the bear’s skeleton. There are a lot of individual little problems that you have to solve.

Can you look back on a project and say “Gee, I wish I’d had better technology then, I could make this look so much better”?

Michael Fink: I can look at Batman Returns and say “Man, I wish we had better technology there,” but the bigger issue for me was “Why didn’t I see that didn’t look good?” I go back and look and stuff and say “Boy, I’ve come a long way. I didn’t catch that 20 years ago – and now I would never let that go out on screen.” Because we’ve all become more sophisticated. When I did CG penguins in Batman Returns, it was the first time anybody’d ever done a CG animal that was a real animal that you would recognize – I mean, psuedopods and dinosaurs are fine.

We were working with pretty primitive tools for lighting and rendering. And that’s where we got hurt on that show. With the penguins. The animation was actually pretty good, but the lighting and rendering sort of fell apart.

I like to think that I’m either developing or using the best technology for the job, and on Batman Returns there isn’t anything that we could have done differently … excerpt that I could have driven the artists a slightly different way, and we could have come up with better renders for the penguins. And I’d be much happier today, 20 years later.

What are you doing next?

Michael Fink: Nothing! I either do small parts of large shows, or large parts of small shows, but I can’t take on a full-on feature like Life of Pi. For Bill Westenhofer, that was nearly a three-year journey. And I can’t take three years away from USC, I don’t want to.

I’m always looking for that feature that’s so compelling that I really want to go after it hammer and tongs and try to get that job. Because when I find that one, then I’ll take the two years’ leave of absence and go work.