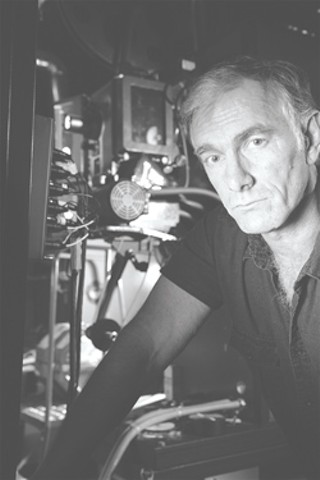

JOHN SAYLES HAS BEEN called the grandfather of the indie film. He’s been called the voice of the American working class.

He’s a director, an actor, and a screenwriter. His body of work is almost impossibly diverse:

Shock-flicks by Roger Corman. An ode to West Virginia coal miners (Matewan). A look at Texas border politics (Lone Star). A sci-fi film about a black space alien (Brother From Another Planet). A chapter from Celtic mythology (The Secret of Roan Inish). A painful look at living disabled (Passion Fish). The hippie reunion film Return of the Secaucus 7, template for The Big Chill. The dark baseball flick Eight Men Out.

Oh, and three music videos for Bruce Springsteen.

This modern day renaissance man will receive a Lifetime Achievement Award this Monday night at the Trustees Theatre as part of the Savannah Film Festival.

Sayles won’t be alone — he’ll be bringing his new movie, Honeydripper, and his old friend and frequent coworker, Academy Award winner Chris Cooper.

Honeydripper stars Danny Glover, Charles S. Dutton, Mary Steenburgen, Keb’ Mo’, and Savannah native Stacy Keach. It’s about what happens when business is down at Glover’s jukejoint in 1950s Alabama and he decides to bring in a young bluesman to perk things up: screen newcomer Gary Clark Jr., who in real life is one of Austin’s most celebrated young guitarslingers.

We spoke to Sayles last week.

What led you to make a movie about African-Americans in the South in general, and the blues in particular?

John Sayles: I’ve always been interested in how, certainly in our culture, integration happened first in sports and in music. Those people, athletes and musicians, would get together and play together — in both senses of the word — before it was necessarily even legal. There’s a real common language there.

I’ve always been interested in the moment when rhythm ‘n’ blues and blues and big band and gospel and county/western and hillbilly music all had an influence on what later would be known as rock ‘n’ roll. I wanted to put my finger on that moment, when it was and what were the factors that led to it.

I started doing research on the evolution of the electric guitar. Right about 1949-50 there was this new phenomenon of a solid-body electric guitar with an amplifier that could really crank out a lot of sound. So you got this sort of funny battle between the piano and the guitar to see which would be the lead instrument, and the guitar wins out within about four years.

That led to a bunch of other stuff and other decisions, which is sort of the situation Danny Glover’s character finds himself in. He has his whole self-image invested in one kind of music, but there’s this other thing that’s about to leave the station. Do you hope for the best and climb aboard?

There’s a parallel with the rise of bluegrass at the same time, also coming out of technology. Bill Monroe basically invented bluegrass by miking and recording acoustic instruments in short songs that could be played on the radio.

John Sayles: That influence extended even to rock ‘n’ roll. Ike Everly was a great guitarist in the Kentucky area, and had a big influence on Merle Travis, for example. He imparted bluegrass, country/western and folk stuff to his songs with the Everly Brothers, and they were in turn instrumental in bringing that country and hillbilly influence to rock ‘n’ roll.

Honeydripper also has something in common with many of your films in that it deals with a marginalized area of the country. You’ve made films about Alaska, West Virginia, the southern border, and now the deep South.

John Sayles: And also Cajun Louisiana, yes. I’m interested in the effect of a time and a place on culture. Culture doesn’t just exist in a place, it also exists in a time. Certainly if you had set the same story in Chicago in 1950 it would have been very different. I want to look at the culture of the moment and take a snapshot of that.

For example, like the scene in Honeydripper when the sheriff walks in to that bar — how come everyone gets all tense all of a sudden? Well, if you know that it’s 1950 in Alabama, you kind of understand why there’s that tension when the white sheriff comes into the room full of African-Americans.

To me the most powerful line in the movie is when Danny Glover says to a young guy, “Take your hat off, boy.” That shows that at the time there was an assumption that if you’re black and you address a white man, you have to take your hat off first. Of course today you can barely get people to take their hat off at the table.

Traditional Hollywood movies tend to take place in “Movieworld.” You see people with certain jobs and you know they couldn’t actually afford that apartment or that car, and the whole thing’s probably shot in Toronto. The scene is supposed to be rural or urban, and that’s all we know. But the richest story stuff always comes out of a specific time and place.

I’ve always been impressed with your grasp of dialect and authentic speech patterns. For example, in Honeydripper, Danny Glover says to Keb’ Mo’ about his daughter, “Don’t you be studyin’ her.” That’s a particularly Southern phrase, not something in pop culture. How do you acquire this grasp of how people from so many different backgrounds actually speak?

John Sayles: That’s actually getting harder to do. There’s less of it because of mass media. I’ve got relatives in the South and I’ve spent quite a bit of time down there. I remember one of the first shocks of my life happened with that old kid’s show called Romper Room. It was shocking for a little kid to go down to Jacksonville and find out that down there “Miss Diane” had a thick Southern accent. That’s when it started to sink in that people don’t talk the same everywhere. I became interested in how people express themselves. That’s including people who will, three or four times a day, change the way they talk depending on who they’re with. You have a policeman who talks one way in the lockerroom, one way in front of the lieutenant and another way if he’s interviewed by the local news.

My ears have been open my whole life. It’s really helped that I had a lot of work experience before I ever got involved with writing and directing movies. I was often the only male when I worked in hospitals, and I’d be the only guy on the floor. I was often the only white person on a labor crew. I’ve worked in places where people spoke Italian instead of English. You start to realize that the way people express themselves tells you a lot about them — not just sociologically but also just in how they choose their words.

In Sunshine State Jane Alexander plays Edie Falco’s mother. Jane’s character is basically a professional Southerner — she’s a drama teacher and an actress, and is sort of like a character straight out of a Tennessee Williams play. But her daughter is very blunt. Their rhythms of speaking are both very different despite the fact that they’re from the same region.

You had this enormously charismatic, larger-than-life cast in Honeydripper. Did there come a point when you had issues with actors improvising your script?

John Sayles: The thing is, we don’t change any lines really. That’s the trick of being a really good actor — they make the lines their own. What I do is get them the script as early as possible, along with a bio I’ve written about their character. Any time a line troubles them, we talk about it and maybe there’s a slight rewording. Usually that happens when there’s a tongue-twister of some kind. You have to realize that with most of the actors in Honeydripper — not Gary so much, he’s a new actor — most of them have done quite a bit of theatre. And there you have a text and you don’t ever change it.

For example, Stacy Keach came literally right off the stage playing King Lear to playing our sheriff. Charles Dutton has done probably a half-dozen August Wilson plays and can handle big reams of dialogue.

You’ve been called the grandfather of indie cinema. There are two schools of thought now: It’s a great time to make indies because distribution is easier with the internet and the growing DVD market. Another school is that the big studios have just coopted independent film. What do you think?

John Sayles: What’s happened is that the distribution is different than what’s getting made. The truth is there’s only so many screens and so many weeks in a year. Certainly it’s true that major studios now mostly have their own specialty arms. And more and more what the specialty arms are looking for is cheap movies — not great or unusual movies, but cheap ones.

They’d be perfectly happy if every movie was a version of The 40 Year Old Virgin, a very well-made comedy that only costs $2 million to acquire, or less. In some ways the specialty arms are like minor league scouts — they want to make Hollywood movies, but get the filmmakers at a bargain price for the first movie or two.

The good thing that’s happening is that it’s easier than ever to make a movie. Not easy, but easier than before. High-definition video exists now. When I started there were three film schools in the country, now there are 300. People in high school know how to use a camera, they know what a panning shot is, they know how to cut on their computer at home. That knowledge was not available when I was starting out. Sundance gets about five or six thousand features a year. When they started they got maybe 12 (laughs). There’s just been a huge increase in the number of people making movies.

But again: There’s only so many weeks in the year, only so many slots for each screen. So what you’re seeing, what’s put up for theatrical runs, is more conservative. The range is pretty wide but you gotta go looking for it.

You know, when you see somebody on the street is handing out something for free, you don’t value it as much. Accessibility blurs our estimations of something. I remember when I would find my favorite song playing on the radio, I’d go, “wow.” But today you can download it for 50 cents and have it forever. Things change.

I do think what you’ll see is that it’s very rare for independent filmmakers to do something like Honeydripper, which is expensive. It’s a period movie. That compelled us to take only five weeks to shoot it. We sort of made it like a low-budget film, though it’s really not.

I’ll end with a stock question you’ve probably heard a million times: What advice do you have for beginning screenwriters?

John Sayles: My two big pieces of advice are, first, don’t just write one script and walk around with that under your shoulder. Write eight scripts. Have lots of scripts ready. You’ll learn something writing each one.

When I got my start working for Roger Corman, I wrote three movies within a year and half. All three were made into movies. I got to see what worked and what didn’t.

Now you can take advantage of a huge opportunity, because you’ve got all these graduates of film school who don’t necessarily want to write. They’re all directors. Find those people who are just starting out. Even if you have to watch 20 movies just available on Netflix. Start contacting those people rather than going to Hollywood right away.

If you get something people can see on the screen, you know, a pretty good showing with a $500,000 movie, then you can go to Hollywood and you’re a lot more likely to get attention. A screenplay takes about four hours to read, and people don’t really read that well, even in Hollywood (laughs). But if they see a movie that’s well-constructed and the dialogue seems good, you’ve got a leg up.

That’s something most playwrights die for, is to have a theatre company perform their work before it’s finished, even if it’s just staged readings. Even with just a home camera you can get somebody who wants to be a director and somebody that wants to be a writer, and see a project up on its feet.

John Sayles will receive a Lifetime Achievement Award Monday, Oct. 29 at 7 p.m. at the Trustees Theatre, followed by a screening of Honeydripper. Chris Cooper is scheduled to be in attendance.