THOUGH"To Kill a Mockingbird" was her only published book, Harper Lee was a writer through and through.

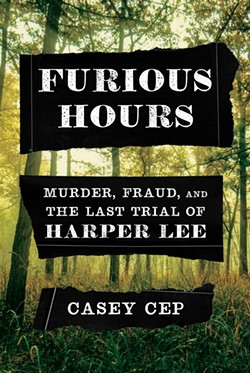

Lee’s foray into true crime writing is detailed in Casey Cep’s new book, “Furious Hours: Murder, Fraud, and the Last Trial of Harper Lee,” published this spring.

After “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Lee sat in on a trial for Reverend Willie Maxwell, a preacher accused of murdering five family members. She was captivated by the trial and began reporting for a novel she never published.

Cep, a lifelong Lee fan, was inspired after reporting the story about the novel for the New Yorker in 2015.

We talked with Cep last week about true crime reporting and why Flannery’s ghost might be stirred this Thursday.

Let’s talk about your decision to begin the story of “Furious Hours.”

I loved “[To Kill A] Mockingbird” as a kid. Harper Lee was an important writer to me.

In 2015, I took an assignment for the New Yorker to write about Harper Lee and the novel “Go Set a Watchman” that had just been announced. It was during that reporting that I found out about the Maxwell case and other books she had tried to write, and I was fascinated. I wrote a short article about the case at the time and then realized there was so much more to say.

Once the article came out, I heard from more people who had met her when she was working on her own version of the case. There were more sources and more material, and it just felt like it wanted to be a book.

One woman wrote to me and said Harper Lee had come for pimento cheese sandwiches for lunch. It’s stories like that that made clear there was a lot more to say about this case and her work on it. For me, as someone who loved Harper Lee, it was the chance to write about this really vibrant period in her life when she wasn’t reclusive, she wasn’t antisocial, she was gregarious and friendly and went to cocktail parties, making her way around the community and befriending people and getting to know sources.

It felt like the chance not only to do some different kinds of writing, like true crime and legal writing, but also to offer people who liked her work a different version of her life, one that looked at her in the prime of her life. So much of the news after [“Go Set a] Watchman” was about her diminished capacity and other people having a say over her affairs. The story felt like a way to really look at her in her prime, when she was full of ambition and undertaking such an interesting and strange project.

I just think she was a writer through and through. What I felt like was the most important thing I could do with this book is remind people that she had tried. Even though there was just the one book, she had tried over and over again. Just because you’re not publishing doesn’t mean you’re not writing. I think that’s especially important for a female artist like Harper Lee. We have a kind of romanticized vision of the male genius who retreats from the world and is slaving over his work. I think, in some ways, she had been underestimated, particularly as a female writer. That was something I could do, too—connect her story to a deeper one about artistry and about struggling and about genius, [which] is not too strong a word for her.

What was your process of reporting this story and writing this book?

With a story like this, most of it takes place in the 1970s, and all three of the main characters, by the time the book came out, were deceased. A lot of the reporting was looking for people who knew them and could help bring them to life. There was a lot of interviewing to get to hear the oral history of these places and these faces.

If you look at the notes of this book, there’s just a tremendous amount of archival work, and that’s everything from local and regional newspapers to academic books on everything from hydroelectric power, because I tell the story of the Tallapoosa River being dammed, to the genre of true crime. I read a lot about how these kinds of stories became popular and their origins and their historical literature.

Part of the book is about the Reverend’s lawyer who then defended the vigilante who murdered him, and that lawyer had had a really interesting political career. There was a lot of reading around mid-century Alabama politics to make sure that I was able to situate his career and use him as a way to look at the larger political story of race and liberalism in the South.

It was a nice first book for me. It let me do a lot of different reporting and research, and then a lot of writing, too. I got to ride around in a lot of different gears.

The frustrating thing, for a lot of writers, is you don’t always get to show your work. There are so many hours of interviews that never make it into the book. My best example of that is I did this wonderful interview with a woman who had grown up in Monroeville and known Harper Lee as a child, and then they went to the University of Alabama together and knew one another in New York. I interviewed her for probably six and a half hours one day, and there is exactly one fact from that interview that made it into the book. It’s the fact that when Harper Lee was working for the airline in New York City, she once took reservations for Laurence Olivier.

I learned a lot from that woman, and I learned deeply about the dynamics of Monroeville and the perception of Harper Lee, but in terms of the actual work product on the page, it’s six and a half hours to half a clause in the book!

There’s background, and there’s deep knowledge that you only get from conversation and the wandering presence of someone.

You’ll be reading the work at the Flannery O’Connor Childhood Home, which is a nice juxtaposition of two Southern female writers and contemporaries.

I love Flannery’s work too, and I find it so interesting that she’s such an odd figure in American literature. I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that she’s in the category of Harper Lee’s peers who did not like “[To Kill A] Mockingbird!” In a letter she writes to a friend, she’s very confused—she felt it was fundamentally a children’s book, and she was confused by its popularity. I don’t know how she’d feel about me coming to town and using her childhood home as a launching point for this book.

But, I like to think Lee was also a religious writer—she was steeped in the Methodist church and obviously this book of hers would have looked at hoodoo and rural Baptist ministry, and I would like to think Flannery would not be offended because we’ll hopefully be talking about religious literature and devotion and the role spirituality plays in small towns and the way people cope with the violence of the world.