ABOUT 30 years ago, Tom Kohler discovered his favorite sign had been painted over.

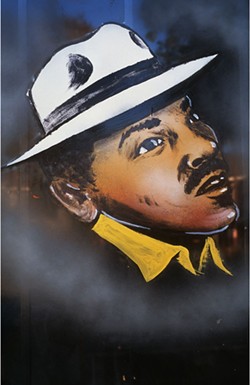

The sign for The Music Lounge, on the corner of Jefferson and Anderson, was hand-painted by Jimmie Williams, a well-respected sign painter in town.

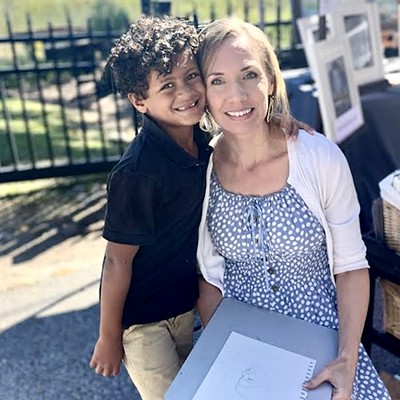

Disappointed to see it gone, Kohler decided to begin documenting Savannah’s unique signage with photographers Michelle Stewart and Susan Earl.

“I found a photographer, Michelle Stewart, who worked at a camera store and she had seen some snapshots I had taken with a Brownie camera,” recalls Kohler. “She was looking at them and was interested, and I said, ‘You want to go out on Saturday and take some pictures?’”

Those photographs are now on view at the Sentient Bean through Feb. 26. “North of Victory: Savannah’s Soulful Signage” shows the rich history of hand-painted signs in Savannah’s predominantly Black neighborhoods.

The culture of Savannah’s hand-painted signs is the richest in the region.

“Because of being interested in [the signs], when I go to Columbus or Atlanta or Brunswick, I’m looking around,” says Kohler. “And if you go into the African-American neighborhoods in any of those communities, you can still find hand-painted signs. But in terms of quality, quantity, and richness—at least from what I see—Savannah has the richest history of this type of work in any of those towns.”

The four artists represented in the exhibition are Williams, Leonard Miller Marcus Polite, and William Pleasant. Of those four, Williams is the only painter still living.

“I’ve been painting signs for about 50 years,” shares Williams. “I’ve been painting and drawing all my life. I just came to it, I really couldn’t tell you how.”

Williams was picked to paint backgrounds for programs in elementary school, but it was by reading his mother’s color Bible that he really got interested in painting.

“It just lit me up,” he says. “I wanted to be able to do that.”

After he began painting signs, Williams says that other sign painters in town took note of his work.

“It’s almost like heritage—it comes down the line,” says Williams. “All the sign painters pick up on you. If you’re alright, got a good work ethic, don’t leave sloppy work and take pride in your work, they pick you up and start talking.”

Williams looked up to the other painters involved in the show, but Pleasant was a special influence.

“When his health started declining, he started coming by my house and telling me about the different churches he did lettering for,” Williams says. “This made me feel privileged, because why would he do that? This man, I used to look at the way he lettered, just sit there and watch him.”

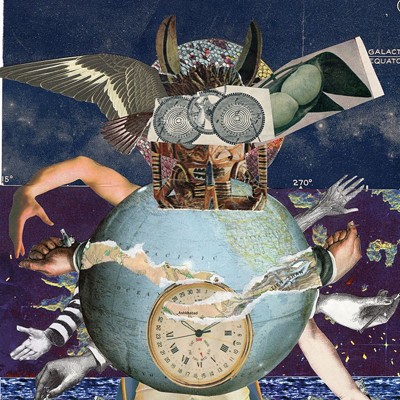

Indeed, Pleasant was incredibly talented, not just as a painter but as a fine artist.

“Whenever there’s some dialogue about [my father’s] work, they consistently separate his signage and graphic design work from his work as a fine artist, and the fact that he was also a well-trained fine artist who did a diverse set of styles,” explains Pleasant’s son Jalal.

“There’s this narrative that he was just some guy who was doing signs with no real understanding of what he was doing. One of the things that I always tell them is our dad attended the Tyler School of Art, which is a part of Temple University. This was at a time when there were very few Black American art students, especially in a school like that and in the 1940s.”

“He was the only one of him,” adds Pleasant’s son David.

“He wasn’t creating these things just from some undisciplined position where he was stumbling,” says Jalal. “He knew exactly what he was doing. I’ve become very angry when they try to present my father in this new light and dismiss more than half of his history.”

Pleasant and the other sign painters excelled at their work, and the businesses in town knew that.

“The city is kind of a canvas, and Mr. Williams working on that canvas has really been from roughly Gaston and Gwinnett south to Victory, and then Jefferson, Barnard, MLK, and Montgomery would be the south streets,” says Kohler. “The number of hand-painted signs you can count in that area—there’s dozens and dozens.”

“That canvas is shrinking,” adds Earl. “There are less and less areas where you’re being asked to make a sign, because those businesses are not there anymore.”

“If you wanted to encourage entrepreneurism, which we say we do, you’d notice the history of entrepreneurism and make people realize it’s doable and we know how to do it and we’ve done it,” insists Kohler.

“The older entrepreneurs that are dead and gone, the [owner of] Sey Hey, for instance,” says Williams. “He ran businesses for 30-some years.”

“Visually, that corner where Beaver’s Barber Shop on MLK is, that corner visually is historic,” says Kohler. “Mr. Beaver was 90 when he died. He cut hair for 60, 70 years—he cut Willie Mays’ hair.”

“North of Victory” protects that vernacular that’s rapidly being erased by development.

“I think you could make the case that one could look around in those neighborhoods and find visual images and say, ‘This is worth preserving, no matter what,’” says Kohler. “We don’t know how to do that.”

“People need to open up their eyes as far as what constitutes something worth preserving,” says Earl. “Not just a beautiful old historic house that’s worth preserving, but all of these signs are part of Savannah’s culture. You can’t just ignore it.”