FOR NEARLY a century, readers have flocked to Kahlil Gibran’s masterpiece, "The Prophet," for its powerful message of unity and the shared spirituality of humankind.

What those readers may not have known is that Gibran was just as skilled at drawing and painting, and that those works of art carry just as powerful a meaning.

“Kahlil Gibran and the Feminine Divine” opens Friday at the Jepson Center.

Donated to the Telfair by Gibran’s benefactor and friend Mary Haskell Minis in 1950, the permanent collection consists of about 130 pieces and is the largest public collection of his art.

As the title suggests, the exhibition focuses on women, the influence they had on Gibran’s life, and the oneness of all people. Women yielded a powerful influence on Gibran, from his mother, who packed up her family and emigrated from Lebanon to Boston to start a new life, to Haskell Minis herself, who was a lifelong mentor.

Some of the pieces are of specific people in Gibran’s life, like Haskell Minis or his sister, Mariana. The most striking of this set of art is “Portrait of the Artist’s Mother,” a painting of his mother in front of a dying lioness.

Most of Gibran’s work are pencil drawings, so when he does experiment with oil painting, like this one, the result is particularly powerful. The anguish on the mother’s face, coupled with the allusion to strength with the use of the lioness, makes this painting particularly moving.

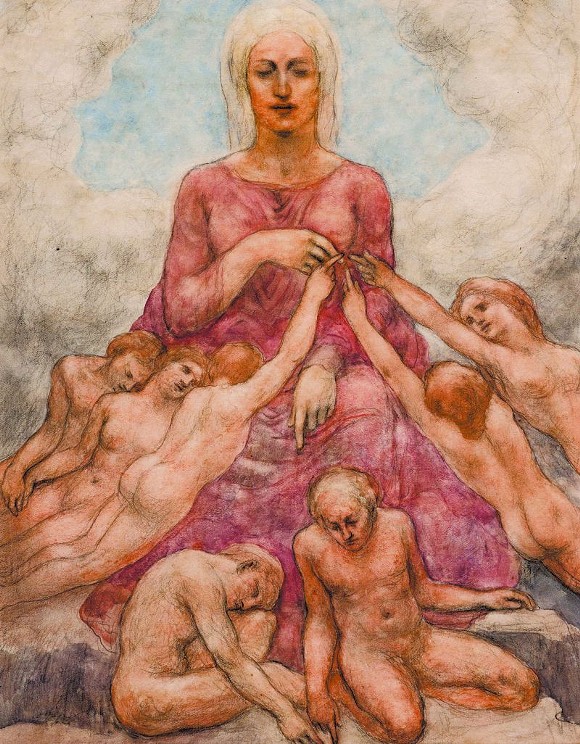

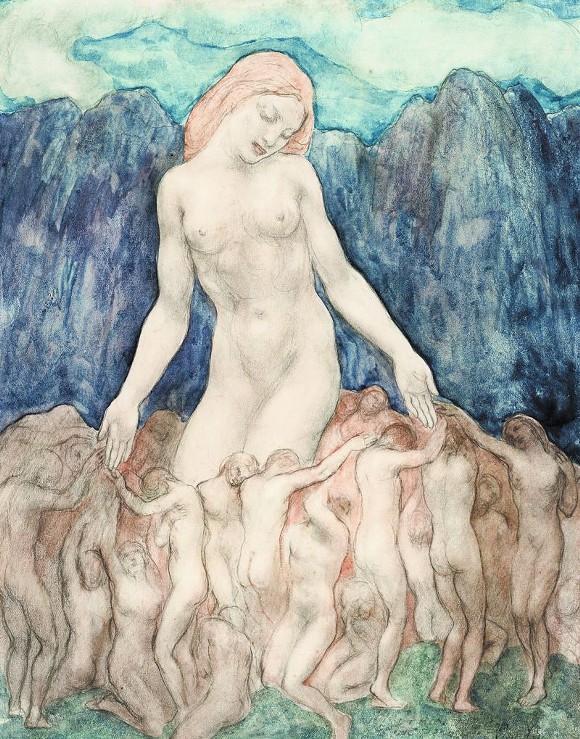

Through this show, Michelangelo is clearly an inspiration, as seen by the musculature on the female figures, a trademark of his. “The Three Are One” is clearly inspired by the Pietà, the pose of Mary holding Jesus’ dead body.

However, Gibran leaves out features of any religion, choosing instead to draw all figures as nondescript.

“He was not a traditionally religious person—he didn’t buy into any one organized religion,” notes curator Courtney McNeil.

“He saw something beautiful about all religions, that all humankind is one. There’s a universality to his writing that I think you also see in his imagery. There aren’t a lot of defining features on these people—they’re not linked to any one point in history or time. You might be reminded of Mary from Christianity, but someone else might also think she looks like one of these ancient goddesses.”

Gibran alludes to Mother Earth in many of the works, making that connection by drawing many smaller figures flocking to a larger figure. Here again, these figures are all very nondescript, most appearing simply as naked human figures.

“The whole thing is very evocative and not specific,” says McNeil. “I think there’s a lot of space for contemplation in these works.”

This show also holds a lot of cultural relevance at an important time in America’s history. As McNeil notes, Gibran’s family was part of a large wave of immigration from the Middle East that began around 1870 and ended in 1924.

“The wave came about because of all this turmoil and violence back in his homeland, but that cutoff in 1924 is because of the institution of the Immigration Act of 1924,” McNeil explains.

“Sound familiar?” chimes in Vicki Scharfberg, director of marketing and PR for the Telfair.

“Really, the more brown-skinned the people of an area, the less welcome they were in the United States,” McNeil continues.

“We are looking to present projects that are relevant to our audiences, projects that serve them. We’re looking to show work that presents a new lens through which to view the daily parts of our visitors’ lives. We’re not telling a story, we’re not offering answers, but we are asking questions.”

As part of that questioning, the Jepson will in May exhibit “Generation,” a collection by Iraqi-Canadian woman Sawsan Al Saraf and her daughters, Tamara and Sundus Abdul Hadi. Like Gibran’s work, “Generation” focuses on humanity and its oneness and explores the misrepresentation and stereotyping of minority, particularly Arab, communities.

Running the two exhibitions concurrently creates a powerful dialogue that Gibran himself would have especially appreciated.

“I think promoting empathy is one of the most important things we can do as an arts organization,” says McNeil.