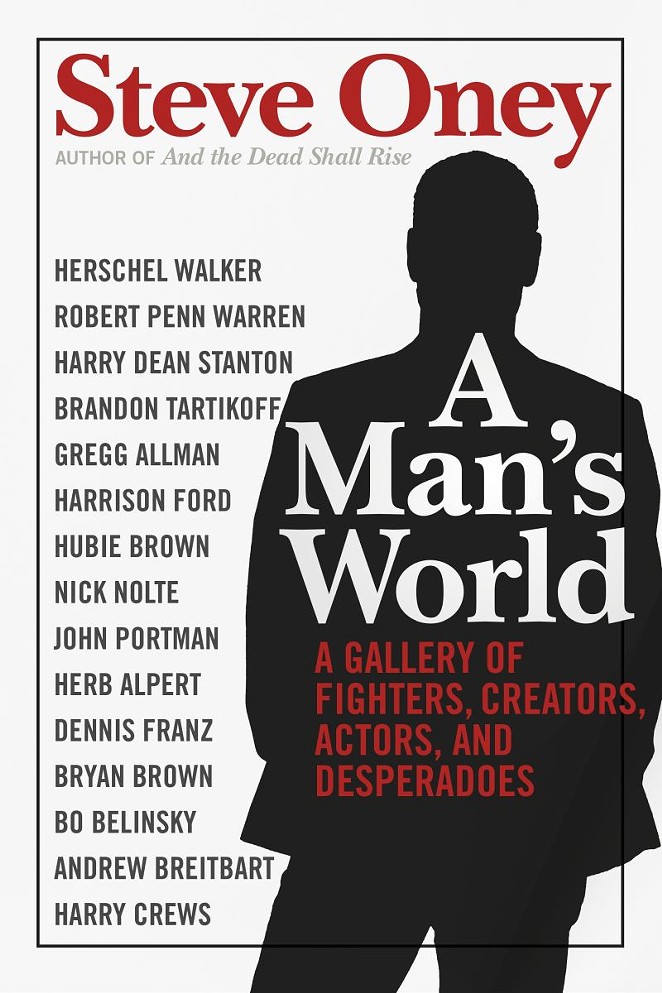

FOR OVER forty years, Steve Oney has been writing for magazines like Esquire, GQ, and the New York Times Magazine.

One common theme he noticed was that he wrote profiles of men he admired.

Oney has written about a variety of men, from Robert Penn Warren to Gregg Allman to Atlanta architect John Portman. All of them inspired Oney; he looked to learn life lessons from the men he featured.

Published by the University of Georgia Press, “A Man’s World” is a collection of 20 of Oney’s profiles.

We spoke with Oney last week.

Tell me how your career started.

I got into magazine writing because at heart, I’m an English major, but I knew I could never be an academic, and I didn’t really want to be a daily newspaper reporter. However, I worked at both the Anderson and Greenville, South Carolina, dailies right after I got out of college. I always wanted to be a magazine writer because I thought that was a happy medium. That’s where you could use the skills of literature and art, except apply them to nonfiction.

I was lucky enough that, after a couple of years of newspaper writing, I got a job at the old Atlanta Journal-Constitution Magazine, which was once a Southern institution but is now long departed. It happened to be during Jimmy Carter’s presidency, and I got a lot of great assignments and was covering stuff all over the country, but for a Southern regional magazine.

What kind of assignments did you get?

It was a magical moment because the eyes of the world were on Atlanta. We were basically allowed to do whatever we wanted. There’s a story in my book, a profile of the great three-time Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Robert Penn Warren. I pitched a profile of him to the editor at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution Magazine. I said, “I want to go spend a week with him in New England,” and they said, “You get him to sign on and you go.”

I think a very good early piece of my journalism was the 1980 Georgia Senate campaign. It was the last campaign for Herman Talmadge, the last of the Talmadge dynasty. In Georgia, it was a very hotly contested campaign. It was the first time a Republican had been elected to a statewide office in Georgia. The winner was a guy named Mack Mattingly, and he became the U.S. Senator. So for the next two months, I’m traveling around the state of Georgia, taking notes, getting ready to write a two-part piece for the Sunday magazine about the fight for Herman Talmadge’s Senate seat.

There was an openness at the paper at the time to think big, and the financial resources were there to enable the writers of the magazine to follow through. It was a time when magazine journalism was a very lucrative thing for the publications. It was never really lucrative for a writer—when you’re a writer, you always feel underpaid, but at least I was paid, and I got great display and good editing.

At the end of my fifth year at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution Magazine, I got a Nieman [Foundation] fellowship with Harvard. It’s a mid-career fellowship; it’s what Harvard has instead of a journalism school. It’s kind of a graduate school, but without the pressure of graduate school. That was a huge break for me and a big change in my life.

What was it like to go from the University of Georgia to Harvard?

The fellowship was at once heady and humiliating. The heady part was the world was suddenly mine. I could audit whatever class I wanted, whether it was a survey of American architecture or I could take, as I did, a class on American painting with the curator of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. I was exposed to a world that was bigger and richer than anything I’d been exposed to in Georgia. But, the humbling part is I would meet 18 year-old kids who were smarter than I was. Kids who were all on a fast track I hadn’t been on as a kid going to UGA.

What do you think has changed in the magazine world since those days?

There are an awful lot of good magazines in the world. My favorite thing in the South is the weekly magazine website The Bitter Southerner. It’s got great stories every week, amazing photography and art, and great columns. They engage important issues, they tell lovely stories, and they tell them well with flair and feeling.

The downside is that the economic picture has gotten darker and darker in the years since I started. At age 22 when I got my first job, it was just a very rich world of publication and everything was on the uptick. Now, magazines are folding; they have fewer staff writers. Conde Nast, one of the biggest publishers, is really downsizing. Hearst Magazines are pulling in. It’s a very tough time economically.

My hope is, though, that there’s always going to be an appetite for true stories well and imaginatively told, and accurately reported. The challenge is to figure out how to pay for that, how to finance that kind of journalism.

The Bitter Southerner is one solution. They have membership, which is one solution. It’s almost like public radio, but it’s a regional magazine version of it.

What effect do you think social media is having on journalism?

Twitter and social media are like McDonald’s. It’s fast food. The great magazines, the great stories, are like going to a fine restaurant where the chef is really breaking ground and serving you beautiful, fresh food. That’s my hope, that we’ll figure out how to make magazine writing the equivalent of slow cooking. It’s going to be a very rewarding experience. Once people realize how great [magazine writing] can be, Twitter and Instagram are not going to be that satisfying. I’m an optimist, though.

Anyone can make a Twitter post, but I in fact would say it takes a lot of skill just to write a straight news story. People can’t do that. You wouldn’t say, “I can paint that masterpiece,” but they know they can’t. But they think they can write that story, and in truth, they can’t do that either.

There’s just something so satisfying about reading a really good story. It has that same quality as hearing a bell ring. It sounds a note you can’t find anywhere else. It’s a wonderful thing to be enraptured in a piece of writing. That’s one of my main pieces of advice of being a writer—the most important thing to learn to be a good writer is how to be a good reader.

How did you choose which profiles you wanted to include in “A Man’s World?”

I’ve been a magazine writer so long I’ve probably written a couple hundred full-fledged magazine features, four or five thousand words each. My agent and I decided, “Let’s get a collection together.” I didn’t quite know how to organize it. We concluded that I’ve written so many profiles of men. I was looking for something, and I was looking to find something about myself while writing these profiles of men. I was interested in them as people, but also as teachers.

I picked what I thought were the 20 strongest pieces I had done over these 40 years, and I broke them into categories because I thought, “What’s been important in my life?” Obviously, these are not limited to men. Women face these same issues. But I wanted to look at it through the lives of these men because I am a man.

There’s a profile of John Portman, the architect who died last year who essentially single-handedly built downtown Atlanta. He went to Georgia Tech and he revolutionized architecture—but these pieces are journalism. This is not a how-to book. John Portman is a very controversial figure. There are a lot of people who dislike his architecture. They think it’s dehumanizing. The piece gets into who the critics are of his approach, whether his approach has been successful or has it damaged the city.

That, to me, is the great virtue of journalism and why this book is not a how-to. It’s factual American journalism.

Why is factual journalism so important?

In journalism, you play it down the middle. It’s hard to find the m iddle. Unfortunately, we live in a time of polarized journalism where you’ve got Fox on one side and MSNBC on the other. Real journalism is not either of those things. Real journalism looks for something much harder, which is the middle path.

It’s always hard to find the middle path; it’s hard to be fair. But that’s what makes it worthwhile. If it was easy, there wouldn’t be a payoff. But when you find that middle path of a story with imagination and fair-mindedness, I think that’s a very rewarding thing to do, and a very rewarding thing to read.