FOR BETTER or worse, the story of Savannah in the Civil War is inextricably tied to the colorful Union general William T. Sherman and his infamous "March to the Sea," which ended here on December 20-21, 1864.

Tour guides, visitors, and barstool historians love to argue about why the commander decided not to put the surrendered city to the torch.

In the first episode of the new Bravo cable TV reality series Southern Charm Savannah, cast member Ashley Borders repeats one of the most often-heard, yet untrue, explanations.

“Listen, when Sherman came down through the South, he burned everything,” Ashley declared. “[But] Sherman did not touch Savannah. Sherman had a mistress in Savannah. She talked him into leaving the city alone.”

No, Ashley, Sherman did not have a mistress in Savannah. But you’re not alone in assuming he did. Innumerable tour guides and countless publications and websites make the same claim.

Though the general and many of his officers had numerous friends in the city—primarily the wives of Confederate commanders the Yankees had served with in the pre-war U.S. Army—it was not a romantic interest that spared Savannah the fate of unfortunate Atlanta at Sherman’s hands.

It was common sense. Sherman had no reason to burn Savannah and every reason not to.

When the Union general and his 60,000 battle-hardened veterans arrived on the city’s doorstep in early December, 1864, they were hungry, tired, and running out of supplies. Though the blue-clad troops had lived off the fat of the land between Atlanta and Macon, the swamps of south Georgia offered little for them to forage.

Savannah represented an end to their ordeal—a place to rest, eat, and be resupplied by the Union Navy, which had a large supply base nearby in Hilton Head.

“We are in sight of the promised land, after a pilgrimage of three hundred miles,” wrote Brigadier Gen. John White Geary, who commanded one of Sherman’s divisions.

But first Sherman would need to rid himself of the roughly 10,000 Confederate troops standing in his way. The defending forces were scattered throughout a belt of earthen fortifications located about two and a half miles west of the city.

Comprising a rag-tag mix of old men and youngsters mixed in with a few regular troops, this hodge-podge Confederate army was no match for Sherman’s forces, and the Southerners knew it. Confederate Commanders ordered General William J. Hardee to abandon Savannah and evacuate his outnumbered brigades.

The city would have to be sacrificed to Sherman’s overwhelming forces so that the Southern army, pitiful as it was, could survive to fight another day.

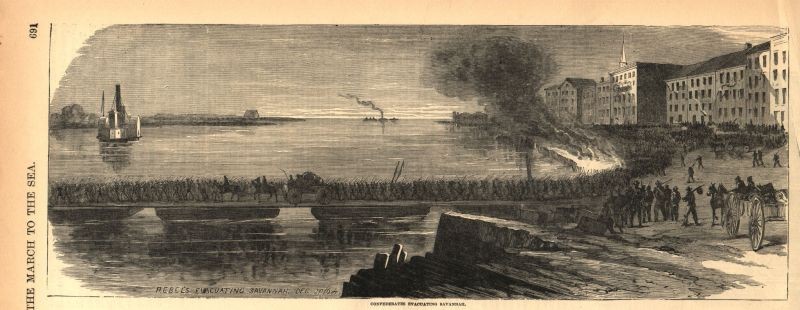

Sherman’s artillery had already begun hammering the Confederate trenches with steady cannon fire when Hardee’s officers put the escape plan into action. Southern engineers scavenged 31 rice flats—wooden barges commonly used in the many flooded rice plantations surrounding the city.

Connecting the barges end to end, the Confederates created a rickety floating bridge stretching from the riverfront in Savannah all the way to the South Carolina shore (using Hutchinson and Pennyworth Islands as anchor points).

The first Confederate troops slipped across the river shortly after sunset on December 20th, 1864, passing in single file as quietly as possible.

“It seemed like an immense funeral procession stealing out of the city in the dead of night,” one evacuee wrote.

The barges were set afire and cut loose around 5:30 a.m. on December 21 after the final Confederate troops passed over. Sherman’s Union troops were hot on their heels.

Ironically, the only artillery actually fired into the city itself (as opposed to the Confederate defensive positions outside of town) came not from Sherman’s artillery, but from the Confederate ironclad warship CSS Savannah, which remained in the city covering the defenders’ retreat.

The Confederate sailors fired on an American flag raised above Fort Jackson and also on a Union artillery unit that appeared on the bluff and began shooting at the ship.

Sherman’s field commanders began raising alarms about the Confederate evacuation almost as soon as it began, but for some reason, the Union general never ordered his troops to give chase or force the Southerners to stand and fight.

This inexplicable failure seems to indicate that Sherman wanted to march his army into an empty city rather a smoking ruin.

Upon entering the city, Sherman’s soldiers put a quick stop to the looting and mayhem the evacuating Southerners left in their wake. The Union soldiers restored order, cleaned the place up, and even distributed food and firewood.

Savannah’s Confederate wartime mayor and council were left in office and firefighters stayed on the job. Savannahians were so pleased with life under the new Union regime that hundreds voted in a public meeting just one week later to rejoin the Union.

The war would rage on for another five months, but Savannah’s citizens were once again American citizens in Abraham Lincoln’s fold. For Sherman and his exhausted, filthy soldiers, Savannah was a kind of wartime paradise—a place to take a break and recharge after their long march.

The blue-clad troops camped in the squares, where they erected wooden shanties for shelter. There were victory parades on Bay Street and even Union Army brass band concerts in Forsyth Park.

High-born Savannah women baked bread and sold it to the Yankees from the ground floors of Savannah mansions downtown. Using sugar and flour she obtained from the occupiers, one Savannah woman reaped a $56 profit (equivalent to $800 at today’s rates) from selling cakes and pies to Union troops.

So while Ashley of Southern Charm Savannah opined, “In Savannah, women are strong, women are powerful, and it’s because our ancestors were that way!” she might have been correct.

Sherman himself slept and worked in the beautiful Madison Square mansion known today as the Green-Meldrim House, a crash pad rivaling even the digs of the well-heeled young cast of Southern Charm Savannah.

In spite of all of this, however, there remains the little-known fact that much of Savannah did burn shortly after Sherman’s arrival. It happened on the evening of January 27, 1865, five weeks after the city’s surrender.

Sherman and his men were preparing to begin the second phase of their infamous campaign: the march through the Carolinas, which rivaled in its destructive results their earlier trek through Georgia.

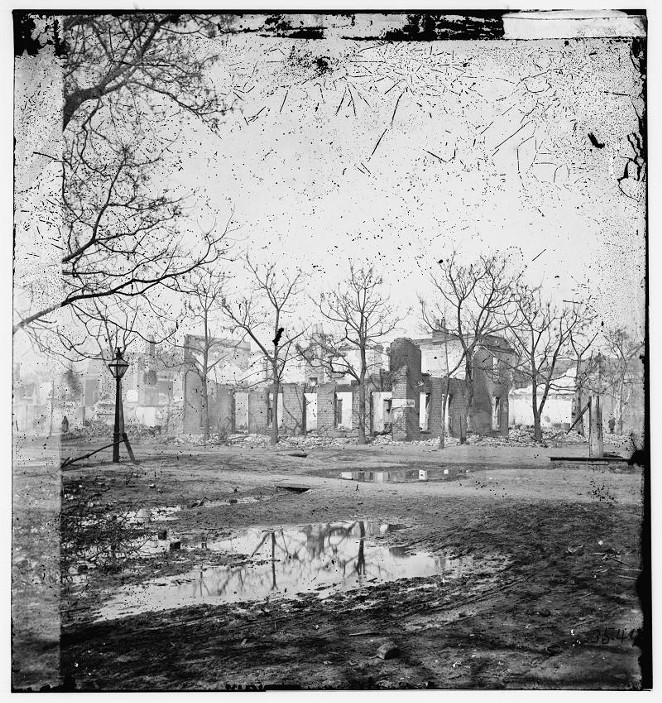

The Savannah blaze began in a stable near Franklin Square and, driven by a strong wind, quickly spread throughout the entire northwestern portion of the city, even threatening wooden ships tied up on the river.

Sometime after 11 p.m., the flames reached a former Confederate arsenal where hundreds of artillery rounds were stored.

Soon the shells were streaking through the night sky and exploding mid-air, sending shrapnel flying into the helpless city. One projectile struck the water tower which used to stand in the middle of Franklin Square, sending water cascading onto the ground below.

Union soldiers—members of a new army sent to replace Sherman’s troops—rushed to the scene to battle the blaze and heave unexploded shells into the river, but the inferno was already out of hand.

By the time the flames were brought under control, more than one hundred buildings were destroyed and an unknown number of people were killed.

The smoldering city resembled “a forest of chimneys,” in the words of one Northern newspaper correspondent.

Leading Savannah citizen William Brown Hodgson (namesake of the Georgia Historical Society building on Whitaker and Gaston streets adjacent to Forsyth Park), who survived the inferno, wrote, “Never while I live shall I cease to remember this night of horrors.”

While it is tempting to blame Union soldiers for starting the fire (and many did), others pointed the finger at possible Confederate sympathizers operating in the occupied city.

It’s just as likely, however, that the fire was started accidentally, like so many of the blazes that ravaged Savannah throughout the 19th century.

In spite of the fire, Savannah survived its encounter with “Uncle Billy” Sherman relatively unscathed—at least compared to cities like Atlanta and Columbia, S.C.

Sherman and his men weren’t the first Northerners to pay Savannah a visit for R&R, and goodness know they weren’t the last. Maybe these Northern soldiers were actually Savannah’s first Yankee tourists!

So no, Ashley, Sherman did not have a mistress in Savannah, but apparently he did fall in love with our fair Southern city.