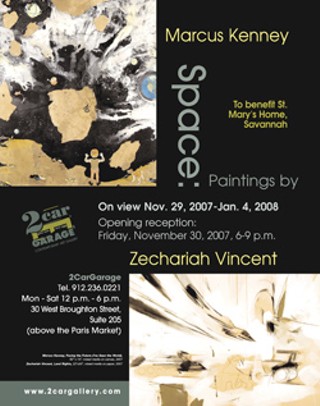

Space. It is dear to an artist’s heart. There’s never enough of it. Here, in Marcus Kenney’s works in this exhibition, it refers to “outer space”.

All eight of his paintings take place in a dark planetary universe filled with meteor showers, flying rocks and debris; little children hurtle through the universe while larger children, frequently wearing space suits and waving American flags, stand by.

The British art critic, Julian Stallabrass, writing about the work of the young British artists in the 1990s, coined the term, “High Art Lite.” There are certain characteristics that he considers essential for this category: nostalgia, mass media references, irony and a combination of the pretty and the offensive, along with a calculated ambiguity in which the artists refuse to define the works’ intentions and, instead, say that it is up to the viewer to determine its meaning.

Although Marcus Kenney obviously does not have the same British references in his work, he is part of the same generation, those who were born in the late 1960s and the 1970s and who were dubbed by the media as Generation X. This group is understandably cynical in response to the hypocrisy in which political action and debate has been replaced by merely giving “correct” names to things.

But that has created a void which can be filled by easy narrow nationalisms and sectarian religious bigotry. For an artist of this generation, the market has stepped in as the only truth, become the relied upon standard. People used to regard art as central to an expression of what it meant to be human. Generation X believes otherwise and has turned the artist into a business man and the artwork into a commodity like any other.

Kenney’s work shares many attributes of “High Art Lite, for instance, a nostalgia for the period of his childhood when the space program was exciting and dominated the media. The work reflects a conservatism, a desire for the comfortable divisions of the Cold War days.

His repetitive use of the American flag is left to the viewer to feel about as he will – is it nationalism or a critique of nationalism? And these collages are truly pretty, using various colored papers; the smaller images of children are cut from old book illustrations.

But as if intentionally to disturb this prettiness, to make the figures less “cutesy”, the larger children have facial features that are jarringly constructed from mouths and eyes cut from magazines.

In “While on the Moon,” a large blonde girl with cut outs of eyes and mouth wears a space suit that sports a big Confederate flag. Since the art market models itself on the entertainment industry and artists are obligated to take on the rock star role of shocking behavior, this flag display in Kenney’s work is no doubt chosen to be controversial.

However, people who care one way or another about the Confederate flag are not your usual contemporary art audience. So no great risk here.

The “space” in Zechariah Vincent’s work reflects the formal element within abstract painting. The majority of Vincent’s paintings here incorporate pencil drawings frequently of birds that have been buried under a layer of gestural paint. The dominant colors are black and white with some pale greens and blues and small areas of red and orange.

These lyrical abstractions are the antithesis of High Art Lite; instead, they are something that now seems archaic in the world of contemporary art – painting, using paint and brush as opposed to collaged assemblages of found objects or computer generated images. The impulse of the abstract painter is to resist the image just as the figurative painter can often neglect the formal abstract qualities to emphasize the narrative.

And here lies the tension and contradiction in Vincent’s work: a pull between political content reflected in the titles of these works, “Land Rights”, “Politico”, “Versus”, “Primitive Intention”, and “Buy American” and the painter’s primary concern with line, color and form.

It is, however, possible to detect a solution to this problem in the calligraphic line that Vincent employs. Words, rather than the image, could become the vehicle for the content.

In 2000, I first encountered the work of both Kenney and Vincent in their collaborative installation exhibition, “Liberal Propaganda.” Each artist had his own installation area. Vincent’s was called, “Campaign Headquarters,” and focused on his “free water” campaign against the rising use of bottled water and its social repercussions. He lived within the installation for seven days.

I felt that these installations were influenced by the German artist and activist, Joseph Beuys. And I thought these two artists were embarking on a collaborative avant-garde adventure.

However, for all I know, he and Kenney are still pursuing their avant-garde collaborations. I know that artists need jobs to live. Money has to be made. Food and shelter require it.

Vincent works as a photographer’s assistant, while in Kenney’s case, the market serves as an employer. But what if the market is also regarded as just a day job, like teaching, like washing dishes, and all the while a new identity, a secret production of genuine merit without strings, without deals, without hope, but with integrity and joy is carried on under pseudonyms?

2Car Garage is at 30 West Broughton Street, www.2cargallery.com, 236-0221.