GROWING up, Alexandra Senfft knew her grandfather was a Nazi, but she never knew exactly what he did. Her family never discussed the particulars of his involvement, only saying he was an envoy. She knew that he was executed in 1947 but never really understood why. It wasn’t until years later, when Senfft did her own research, that she found out her grandfather had committed war crimes.

This history, Senfft says, is familiar to many German families, who don’t discuss the horrors of the Holocaust. But to invoke an old adage, if we don’t know our history, we are doomed to repeat it.

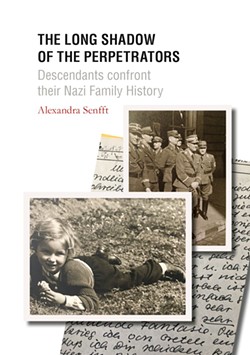

Senfft is the author of “The Long Shadows of the Perpetrators: Descendants confront their Nazi Family History,” and she will present a program this Friday at Temple Mickve Israel on the subject.

We spoke with Senfft last week.

Tell me about your family history.

Well, I grew up knowing that my grandfather was a Nazi. There was never a debate about that in my family. My father, who was a very progressive person, always taught me about history knew that [my grandfather] was a Nazi and I always despised it politically.

However, in my mother’s family—and this grandfather was my mother’s father—there was a lot of talk about him and the fact that he had been the envoy of the Third Reich to Slovakia. However, there was never any discussion about what this in effect had meant. When I grew up, I thought, “Well, he was a ‘diplomat,’ wasn’t he?” Because that was the kind of position he had. And I thought, “Well, diplomats don’t do any harm, do they? They sit at desks and they sign things and they don’t go out and kill people like the Nazis did.”

And of course, there was definitely a silencing in my family, a huge denial as relates to the fact that my grandfather was involved in the Holocaust because as the envoy of Nazi Germany, his role was to represent his country in Slovakia and to convince the Slovak people that it would be in their interest to act on behalf of Nazi Germany, which I’m afraid many voluntarily and glady did.

When I was younger, I never really thought much about what this, in effect, meant. What did he really do? Because in my family, he was portrayed as a “good Nazi”—someone who didn’t do anything bad; in fact he was depicted as a “victim of the times”. And I grew up understanding that you don’t really ask any critical questions about it, because my mother, who was the eldest of the six children, would get very upset if I started talking about her father. She was still a teenager when he was executed, and she never really understood why, also because so many of his “comrades” made a career again after the war. First of all, her mother never told her the truth, and secondly, the majority of the German society was in denial, not talking about what they had witnessed, not talking about whether they had been bystanders, and especially if they had victimized others.

So the family history I’m portraying is in a sense quite a normal German family history. Of course, my grandfather was more exposed because he wasn’t an ordinary soldier, he was an envoy.

I started analyzing after my mother’s sad and premature death and what had actually been wrong with her, why she was so often depressed. The more I started researching and investigating, the closer I came to what I call the truth, and that is the fact that my grandfather had been a Nazi perpetrator by signing deportation orders for the Slovak Jews, which of course meant most of them were killed in the concentration camps.

Next I understood how the silence worked in my family and how it actually works up to this very day in the German society, because most Germans are still afraid to actually look into their own families and take up responsibility in the sense of confronting the truth and speaking up.

Why do you think people don’t speak up?

People tend to be loyal to their elders, to their parents and people they love, and they tend to see them in a good light. Who wants to know that a parent or grandparent was involved in mass murder?

Even being passive was some sort of action and went into this creating this huge crime, and it’s very hard to get people to look at something that is evil and to relate that to themselves. To acknowledge that your own family member may have been--to whatever extent—involved in the Holocaust: that’s a horrific thing.

The feelings of shame, feelings of guilt, were passed on through the generations, as well as the silence and the denial. If you’re taught by your parents that you don’t speak openly about something terrible like that, you will become silent yourself, because children learn very quickly that you shouldn’t be touching taboos.

The first generation knew that they had done wrong. Even if they had maybe not actively done something wrong, but just by looking away, they had done something. Of course members of this generation didn’t tell their children, “Look, that’s what I’ve seen or done and it’s horrible,” because children would come back to them and say, “Why didn’t you react? Why did you not do anything?”

How do you think your family reckoned with their own complicity, if they did?

You don’t need the Nazi system [as an example]—you can look at any other kind of system where crimes are being covered up. When you boil it down, the mechanisms of denial are very much alike. We think we should be loyal to these people, and that’s the moment where we become complicit albeit involuntarily, but we don’t even notice it.

Now, I’m not comparing the Holocaust to other issues—they cannot be compared because we’re talking about one of the biggest crimes in modern history. However, when you start actually looking into why people acted the way they did—and still do, of course—you can draw parallels to other conflicts that we’re facing today. It always comes down to this question: are we ready to say “no” in a specific situation? Do we risk being excluded from the network that we think we should be loyal to?

If we don’t reflect on the feeling and the narratives that were passed down the generations, we are prone to repeating many mistakes. This applies to politics nowadays—because why should we look at the past if we don’t draw any conclusions for today? The lessons from the past can teach us to form our attitudes today.

German scholarship and politics have worked through the Nazi era to an exemplary extent, but that has not been the case in the private arena. For many German families, the crimes were always committed by someone else. We will not understand how systems like the Nazi system can come about if we remain in constant denial. Many Germans only looked at the big figures like Hitler and Goebbels and said, “Well, they did it.” But no, it’s people like you and me who actually became instrumental in this crime and we need to acknowledge and stand up for it.

The generation that experienced the war as adults didn’t only remain silent about what happened, but it would often see itself as a victim to the war. Well, of course it’s true that Germans also suffered during the course of the war, but if you start a war you cannot expect not to become victims yourselves. It’s time to face up to the fact that the Nazis came from the midst of our families. When you look at the far-right, people often tend to portray themselves as victims and with the attitude of a victim new harm is done.

What can we learn from this part of our history?

We have to look out for what racism does today, any kind of racism. I think this is an imperative, especially now that we’re facing the far-right everywhere again. We need to really look at our own patterns of thinking.

Democracies are not something that are just here to stay; you cannot take them for granted. You have to struggle for democracy and human rights every single day. It’s such a treasure that came out of the catastrophe of the Second World War that democracy was brought to us and we must defend it, especially now that people are beginning to move their feet again and become destructive, that’s frightening.

Dinner and Program