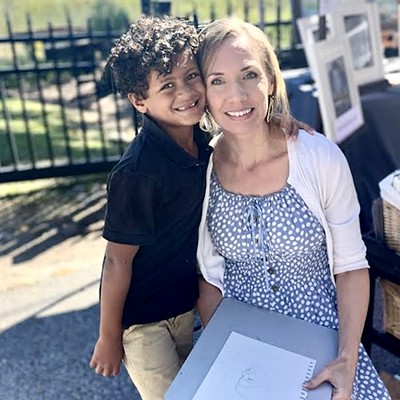

"IN 1992, my advisor at Princeton gave me a kind warning—I should maybe rethink my concentration of study because the scholarship of African American art might be a fad," says Dr. Margaret Rose Vendryes.

Recalling this conversation, she chuckles—this was both well-intentioned advice and clearly an absurd statement.

“I stood my ground and it was worth the effort. African American art is so fresh within the American canon. It is definitely not a fad.”

Now a noted historian, lecturer, and visual artist, Dr. Vendryes points to the Telfair Museums’ current exhibition, The Visual Blues, as proof of this fact.

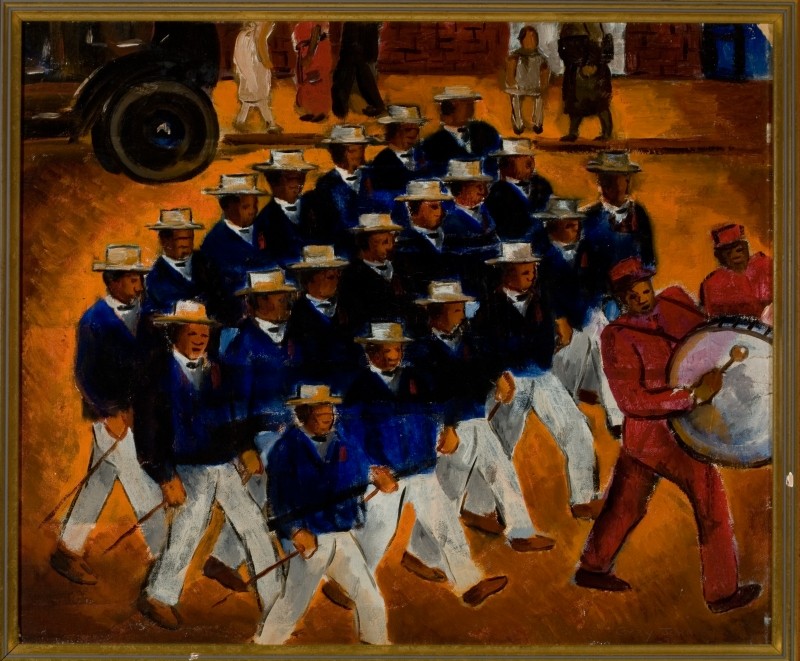

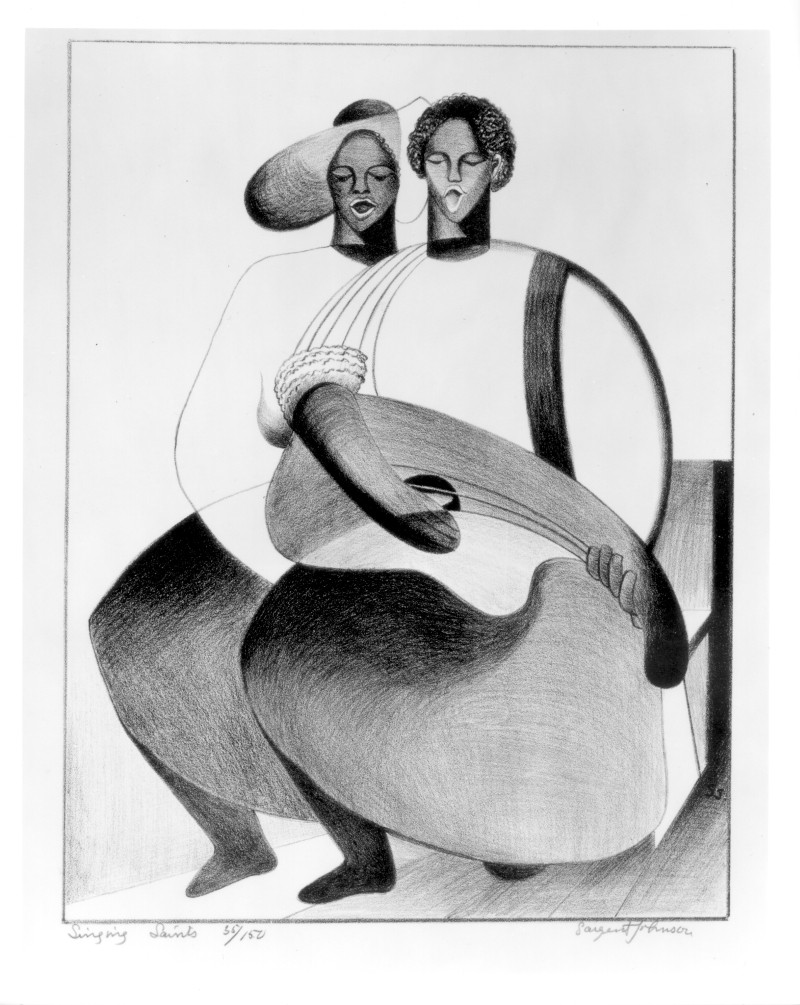

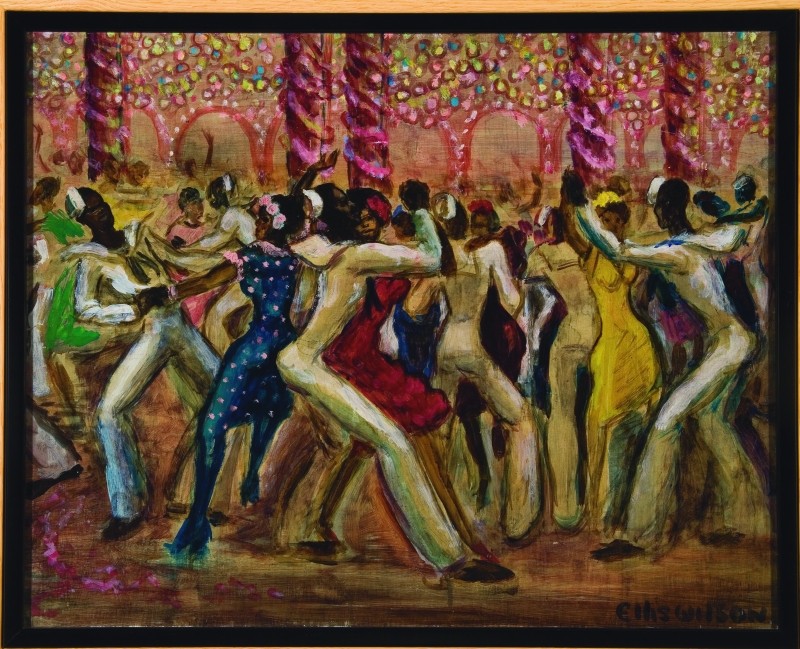

The Visual Blues is a collection of 49 paintings, photographs, prints, and sculptures exploring the dynamic relationship visual artists had with music and musicians during the Harlem Renaissance.

This Thursday, February 5 at the Jepson Center, Dr. Vendryes will give the opening lecture for the exhibition. She will expound upon the vibrant artistic history of the Harlem Renaissance.

During the interwar years, from about 1919 to 1940, African American art, literature, poetry, music, and culture flourished.

“Before, African Americans had no visibility as visual artists and were in the background as musicians and composers,” Dr. Vendryes says. “The Harlem Renaissance was the opening of the visual art world to African Americans as subjects and as makers.”

While the outburst of creativity activity was not limited to the New York City neighborhood of Harlem—it was the hotbed.

In Harlem, visual artists like Romare Bearden, mixed with musicians like Duke Ellington, and literary giants like Langston Hughes. Legendary venues like the Apollo Theatre provided space for black society to inspire and be inspired.

“Harlem was really a place where artists came together. There was a rich community there,” says Courtney McNeil, Telfair Museums’ curator of fine arts and exhibitions.

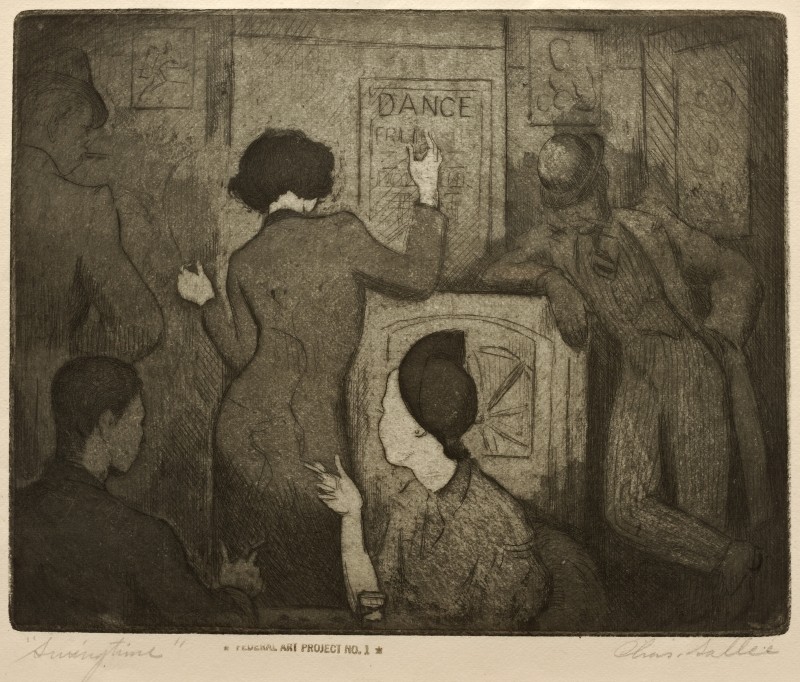

Images on display chronicle the cultural boom. Billie Holiday croons through a blue haze in one painting. An etching by Charles Sallee captures the loose and free late night vibe, where hips swayed and thinkers philosophized in the corner.

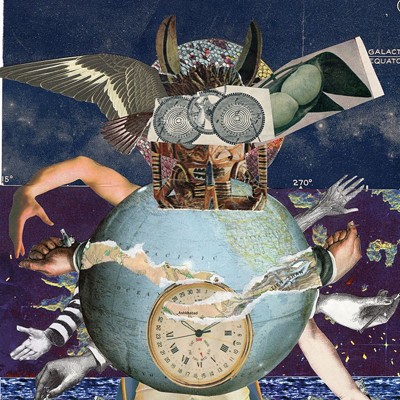

While some works depict lively public spaces, others reveal the intimate influence jazz had on the way visual artists composed their works.

“With Bearden, you can hear his work. He worked with jazz in his ear,” Dr. Vendryes says.

This type of creative mingling is a hallmark of the artistic period, making this exhibition holistic as well as innovative.

“There have been a lot shows on the Harlem Renaissance circulating over the years but this one puts a new spin on the subject by narrowing the focus to the relationship between the visual arts and the music,” says McNeil.

Fortuitously, this exhibition lines up with the 2015 Savannah Music Festival, strengthening the conceptual backing of the exhibition.

Telfair will also offer a Free Family Day and Concert on March 7 with performances by the Savannah Children’s Choir, Beverly “Guitar” Watkins, and the King Bees.

In addition to examining music and art, the collection also integrates the Harlem Renaissance’s connections to the South.

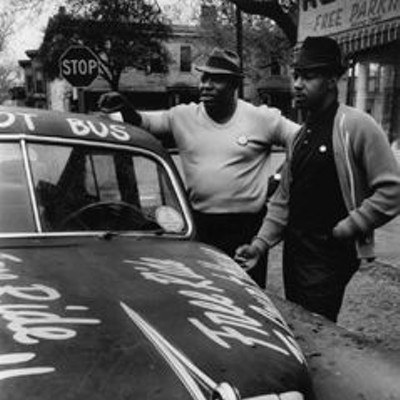

Beginning in the early 1900’s millions of African Americans moved from the South. Known as the Great Migration, this created dense black communities in northern cities.

McNeil points out how, “you have a huge number of factors, from the Jim Crow laws that existed on the books to horrible, illegal activities, like lynchings,” causing the mass exodus from the country life many blacks knew in the South.

Exhibited artists Beardon, Dox Thrash, and William H. Johnson, among others, left the South. This narrative was alive within northern black communities. “Some of the rural scenes celebrate a shared history of Southern origins,” McNeil says.

Dr. Vendryes explains how Johnson “cultivated a naïve style focused on folk art even though he was trained in Paris. It was a kind of homage.”

Southern heritage, along with the improvisational spirit of jazz, permeated the era’s visual language. This exhibition beautifully showcases how during the Harlem Renaissance, artists—visual, musical, poetic, and otherwise—held the expression of their community and culture at the forefront.

Organized by Louisiana State University Museum of Art, The Visual Blues unites works from leading museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

“It’s exciting that this exhibition is taking place at all. It never would have happened when these works were made. There is a lot of excitement that these objects create. Putting them in the same room, it’s a party,” says Dr. Vendryes.

She says in a moment of contemplation, “We have a lot to celebrate. I have seen changes in my lifetime, in my adult lifetime, which is pretty great.”