ONE OF the positive side effects of America’s recent focus on memorials and monuments is that more people are being exposed to more history.

I’m always of the mind that the more history people study, the better.

Savannah is learning about the segregationist history of former Gov. Eugene Talmadge, for whom the bridge crossing the Savannah River into South Carolina is currently named.

As we’ve learned watching the effort of Savannah City Council to rename the bridge, the actual fault for the name lies with the state of Georgia, not with us.

However, Savannah has its own blind spots with regards to our shared history.

Any time you bring up our bridge, people inevitably offer their own favorite suggestion, prompted or not.

The usual crowd favorite is Tomochichi, the Yamacraw chief who facilitated James Oglethorpe’s settlement of the area.

Oglethorpe himself is often mentioned, along with civil rights activist W.W. Law.

Interestingly and disappointingly to me, the name of Savannah’s first African American mayor, Floyd Adams Jr., is rarely suggested by people of any background or political persuasion. Perhaps this curious phenomenon is better discussed in another column some other time.

One suggestion we didn’t hear much until recently was Girl Scouts founder and Savannah native Juliette Gordon Low. Her name is the one the Georgia legislature is now pushing hard to put on the bridge, despite our City Council opting for the incredibly boring but controversy-free name “Savannah Bridge.”

Unfortunately Low’s name wouldn’t remove all vestiges of segregation, as the Girl Scouts of America itself originally excluded African American girls.

You could certainly make the case that Low was progressive and enlightened for her time. You could certainly make the case that the Girl Scouts of America have done great things for the empowerment of girls and young women since then.

But objectively, there’s not much sound justification for putting Low’s name on the bridge given the context of the discussion — especially as there’s not exactly a shortage of references to her here already.

One name you absolutely never hear — probably because most don’t know he’s associated with Savannah — might be the no-brainer of them all.

Savannah native John C. Frémont was the first Republican candidate for president of the United States. He was one of the key figures in the settlement of the American West, and arguably the key figure in the settlement of California, now home to more than one in eight Americans.

An ardent abolitionist, as a Union general Frémont emancipated so many slaves so quickly during the Civil War that he was reprimanded for it by President Lincoln.

That’s right — John C. Frémont was more anti-slavery than the Great Emancipator himself was comfortable with.

While in the U.S. Army, Frémont was responsible for giving Ulysses S. Grant his first key command. Yes, that General Grant.

If you don’t think that’s a big deal, ring up your dead Confederate ancestors on the ol’ Ouija board tonight and ask them if they would prefer to have faced Grant or someone else.

(If you’re wondering, Frémont was one of only two Georgia natives to serve as general in the Union Army.)

John Frémont almost certainly would have made a better president than James Buchanan, the corrupt pro-slavery Democrat who beat him in 1856 and who is unanimously considered by historians to be one of our most disastrous presidents.

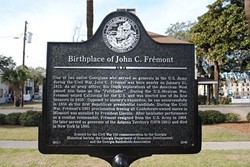

But just about the only mention of Frémont in his hometown is a Georgia Historical Society marker in Yamacraw Village near where he was born in 1813.

There is a very small society here named for him, and also to their credit, Georgia Historical Society did honor Frémont at the 2013 Georgia History Festival.

But otherwise, virtually nothing in Savannah about this native son who was a pivotal figure in American history. Why?

The easy answer is that until very recently Savannah and the state of Georgia were politically dominated by the side that lost the Civil War, namely racist pro-segregation Democrats like....

Eugene Talmadge himself.

Needless to say, they weren’t going to honor the memory of a Republican former Union Army general.

And they certainly weren’t going to honor one known for being one of the fiercest abolitionists of his day.

Of course, it’s far too late in the game for Frémont to get his due and have his name on our bridge. As I write this, it seems inevitable that the well-funded, eleventh-hour effort to put Juliette Gordon Low’s name on the bridge will be successful.

And if so, that will have its own ramifications, unfortunately.

In any case, at a minimum I hope this discussion will spark interest in reading more about Frémont and other important figures with ties to Savannah, bridge or no bridge.