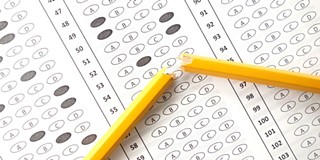

I MIGHT be the only one, but I loved standardized test time as a kid.

By fifth grade I’d already ascertained that the world was a messy and inexact place, and I so appreciated that each precisely-worded question about the correct placement of a comma or how many apples Jack had if Patty took three-fifths of them corresponded to one exact answer: A, B, C or D.

I dorked out over my perfectly-sharpened No. 2 pencils. I waited breathlessly until the teacher said it was time to break the seal on the wheat-colored packets. I filled in the bubbles madly, knowing if I finished early I could read my new issue of Sassy magazine.

No one ever talked about the scores, and as I far as I remember, no kid was ever left behind because of them.

If you have a child in public school, you already know that standardized testing has gotten a whole lot messier and inexact. Maybe there was even a tantrum Tuesday morning, before every 3rd through 8th grader in the Savannah-Chatham County Public School System sat down to the sealed booklets of the Georgia Milestones Assessment System (GMAS). Fortunately, I was able to calm down with a second cup of tea.

Tempers are high and stakes are higher this week: Those in grades 3, 5, and 8 must pass the GMAS to advance to the next grade level. High school students also have subject-specific versions, which make up 20 percent of their final class grades. Students have been filling out practice worksheets for weeks, some staying in at recess.

Given over three days, the GMAS is designed to measure students’ knowledge of language arts, math, science, and social studies in relation to the Georgia Standards of Excellence introduced by the Georgia Dept. of Education in 2010, our state’s “homegrown” version of the federal Common Core standards. It replaces the CRCT and other tests, streamlining students’ performance in order to track them towards college or a vocational career.

And no more of that No. 2 pencil nonsense: the GMAS is administered mostly online, transitioning completely to computers in its fifth year.

This be-all, end-all arbiter of educational progress debuted for the first time last year. Across the board, SCCPSS students performed abominably. Elementary schools that once boasted 90 percent and above proficiencies in reading and math fell below 50 percent. Already-struggling schools that had low performance on previous standardized tests showed pass rate percentages in the single digits. At one high school, only 7.6 percent of ninth graders passed the composition and literature section.

That was expected: Almost every school in Georgia earned pathetic scores on the GMAS, which local and state academic officers chalked up (oops, I mean “dry-erase markered”; who uses chalk anymore?) to the rigor of the new test and the need to ramp up classroom instruction to meet the standards. But for some teachers and parents, last year’s poor marks don’t reflect what’s happening in the classroom but innate problems with the test itself.

Research about the fallibility of standardized testing in general abounds, as do reports on its tendency towards cultural bias and outright absurdity (for real, Google “pineapples don’t have sleeves”). Even in its newness, complaints about the GMAS are multiplying. Poorly written questions and subjective solutions with more than one answer frustrate students and stump educators who have to “teach to the test.”

“It’s horrid,” one local teacher told me. “How is a third grader supposed to ‘check all that apply’ if they can’t understand the question?”

Worse, children worry tearfully that they won’t advance to the next grade if they perform badly.

“It causes so much stress,” laments this 20-year veteran of public school classrooms. “And stress impedes learning.”

I’m practically in tears myself about the section of “open-ended” math questions, like this example taken from Gov. Deal’s Student Achievement page:

Q: Hector says that any multiple of 6 can be divided into 3 equal groups. Is Hector correct? Explain your answer using words, symbols, or pictures.

Don’t even get me started on how we now use “words and pictures” instead of numbers. But doesn’t a question like this have less to do with math skills than it does about a child’s ability to type and draw? What if poor Hector is a math whiz but English is his second language? And why are we spending all this time and money on testing every student if the data is only being used to advance those in certain grades?

The answer is a helluva lot more obvious than a five-paragraph essay about fractions. Standardized testing is big business—a multi-billion dollar industry based on the reductive notion that all students can be tracked by a single norm. Socioeconomics, home life and different learning abilities are not taken into account, in spite of the proven correlation between poverty and poor test performance.

“It’s not a real assessment of a student’s skills or abilities,” says our teacher. “No one looking at these answers knows the child or what they’re capable of.”

That’s part of the reasoning behind the “opt-out movement,” a group of parents who are exercising their right to refuse to take standardized tests across the country. Twenty percent of New York students opted out last year, and last week a school district in Lee County, Florida voted to refuse state-mandated testing for its entire student body. Opt Out Georgia reported 1,500 refusals last year; membership is now over 4,000 across the state and growing exponentially. (Go ahead, draw a picture, Hector.)

“By opting out, we are returning the assessment authority back to the teachers where it belongs,” says Jenny McCord, an SCCPSS parent whose son will sit out the GMAS this week.

“We are making a statement that education policy is broken. It is the teacher’s authority to assess student knowledge.”

Opt-out parents say that it would be one thing if GMAS were being used to identify weak spots in a child’s abilities to amend their educational plan and turn around failing schools. But it’s actually the data that matters most, especially at the state level, where Gov. Nathan Deal wants to use the rankings to appropriate the lowest-performing ten percent of Georgia’s public schools and hand them off to be run by a private “charter school management” company.

Gov. Deal’s “Opportunity School District” would essentially establish a state-wide charter school under the sweeping arm of Paul “Chainsaw” Vallas, who gutted public schools in Chicago and post-Katrina New Orleans. Depending on who you ask, he achieved success, if you measure success, well, by standardized testing. But massive displacements and “counseling out” of low-scoring students and those with special needs were also reported, showing that higher scores come at a cost to communities—literally.

“What the Opportunity District will do is take non-profit, public entities and turn them into for-profit charter schools—but our local school boards will be still be paying for them,” points out McCord.

That’s the other piece fueling the opt-out movement in Georgia: That the intention of the GMAS isn’t to educate kids but further the privatization and profitability of failing schools. If the state doesn’t have the GMAS scores, it doesn’t have the data to identify those schools—or implement the charter school model.

McCord says opting out is straight-up civil disobedience. But the law is already on her and other parents’ side: The Georgia Senate recently passed SB355, which removes any punitive consequences for ditching the GMAS or any another mandated tests.

In spite of this legislation, however, current SCCPSS policy dictates that those in grades 3, 5 and 8 with subpar GMAS scores—or no score at all—will be officially retained. There will be an opportunity to retest in June, and should a student opt out again, parents can file an appeal.

A SCCPSS administrator confirmed that the appeals process starts with a meeting between the parents, the principal and one or more teachers familiar with the student’s performance and proficiency to determine whether the student ought to move up a grade.

In other words, a real assessment.

That would cause some chaos if the opt-out movement gains ground here like it has in other states, and Gov. Deal and the GADOE would have to go back to the drawing board (where they should be forced to solve algebraic equations using Egyptian hieroglyphs and a banana-shaped eraser).

Look, we’re never going back to a time when things were as simple as A,B,C, or D. We need educational standards, and there’s nothing wrong with measuring our kids’ progress. But the GMAS doesn’t have the proven capacity to wield so much power, and standardized testing should not act as the vehicle to privatize our public schools. Neither should it be used to label a student as incapable of learning.

Yet it is plainly useful as a way to galvanize communities to stand up and reclaim public education—a lesson far more valuable than any test.