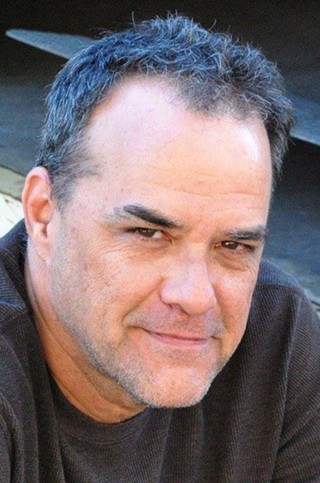

Basik Lee is reflecting on what it means to be a rapper in Savannah. “I lived in Jersey my whole life,” he says. “Everybody’s like ‘You gotta go to the big city, you gotta go to these places and do your thing.’ For me, it’s not where you are, it’s who you are.”

A founder of the hip hop collective Dope Sandwich, Basik – his real name is Stephen Gerald Baumgartner II – is also a poet, a songwriter, a musician and a break dancer.

For nearly six years, he’s hosted Hip Hop Night at the Jinx, where Dope Sandwich came together and where members of the city’s extensive hip hop community congregate on Tuesday nights.

“Honestly,” he explains, “I really appreciate being in Savannah and being able to work on my rhyme skill. There’s a lot of opportunities here that I wouldn’t have received back in Jersey.

“I couldn’t be doing a show at a club there, walk around the corner to another club and be like ‘Yo, can I borrow a mic?’ I couldn’t just call up somebody real quick and say ‘I need a DJ right now, could you come on through?’”

Originally a loose–knit group of rappers, DJs, dancers and artists, Dope Sandwich these days is essentially the core of three founding MCs – Basik, Righteous (Willie James Smith II) and Knife (Kedrick Mack).

They’re dropping a new, all–original CD this week – titled after the private name the three have always used to refer to themselves: Union of Sacred Monsters.

The 16 tracks on the album were written collectively, using beats composed by members of the extensive Dope Sandwich community (rappers Zone–D and Blue Collar, both of whom recently moved away from Savannah, were equal contributors to the recording).

Each MC has a distinctive voice and vocal style, the words fly past at breakneck speed, each set of lyrics telling a different story – some of them from–the–heart true, some a little less so.

There is, however, none of the high–concept bragging, buffoonery and misogyny that typifies so much of commercial rap. Dope Sandwich’s philosophy is, and has always been, keep it real.

“You could have a guy that’s just the complete stereotype of a gangsta rapper,” Knife says, “but he could actually have thoughts, dreams and aspirations, and fears and doubts, but as long as that’s coming across in your music ... it’ll always have that balance as long as you approach it like you’re a real human being. You’ve got to put yourself in the music.”

Role playing

The track “Take a Walk With Me” begins with a few simple piano figures and some ominous strains of violin. Then the beat kicks in, and Basik begins to rap:

Met a man with a dent in his heart

Ran with the scent of a shark

Said he could end my dilemma

Presented a spark

Try to fight it ‘cause I know it ain’t right

To head for the dark

But he keeps saying, come on

Take a walk with me.

“That was actually a free–flowing poem that I wrote a long time ago,” Basik says. “And one day I heard this beat and I just went with it. I was like ‘Man!’ The poem was only the first verse, and I just wrote the second verse recently. It was something I always wanted to finish – it was almost like I was waiting for that right moment.”

The song – which is punctuated with minor–key snatches from classical chorus music – is about temptation.

“People like to say ‘I fell into that stuff.’ Hey, it’s there, it’s always there. There’s nothing to make a big deal about. It’s just always going to be there.”

Righteous explains that the beat can also inspire an entirely fictional storyline.

“Sometimes we’ll be like ‘Hey, this instrument right here makes me think of a robbery. Well, what if we each told a part of the story?’ Then we’ll sit down and give each other roles: ‘I want to be the guy in the car.’ ‘I want to be the guy who has to crack the safe.’ And then from there, we go ‘All right, you write your part, I’ll write my part, and we’ll try and make it cohesive as a story.’”

“The Job” is the album’s robbery tale; “Rat” is the sort–of story of Dope Sandwich itself.

“Both Basik Lee and myself have musical backgrounds,” Righteous says. “We were both doing music before we got into rap. So even when it comes to like ‘Hey, you have to do this within 16 measures to express yourself,’ OK, we know how to count it.”

On “This Pen,” the rappers declare the source of their power:

This pen taps into the energy inside of me

A catalyst awakening, the voices in my head that say hi to me

Try to speak, while trying to keep me sane

But honestly, claiming insanity on the mic is so cliche

I try to be the MC that always keeps the pen beside of me

Everything tends to inspire me

“All of it’s poetry to me,” Basik explains. “I started off doing poetry, and it led into this – starting to rhyme by just putting the words to the beat, and how the technique of putting it to the beat made it different.”

Righteous, who’s also a comic book artist, says his songs are a way of giving voice to his “alter egos. For me, it’s like as I’m writing these characters, and I have these characters in my head, the rhymes allow me to portray those characters in a song,” he says. “So I kind of get to act them out.

“It’s definitely just an outlet, and it’s also therapeutic. I’ve learned a lot about myself – you sit there and you write something, then you read it back and it’s just ‘Man, I didn’t know I actually thought that,’ until you hear yourself rapping it and you think ‘I’m kind of an angry guy at times!’

“Which is in contrast to how I really am. I’m more quiet and laid back. But on the mic, that’s how I express myself. I let it all out on the mic.”

Crank up the volume

“The best analogy,” says Knife, “is pro wrestling. It’s like, you’re a character to a certain extent. But your character works, and you get over depending on how true your character is to you.

“I very much approach it as Knife is a character; Kedrick is a person, and sometimes I use Knife to get across what I feel – most of the times, I’m just rapping.”

There is some explicit language on Union of Sacred Monsters, but not much, and in keeping with company policy, it’s all part of making that particular song feel as real – to the guys – as possible.

“There’s a lot of times I’m writing something, and once I get it out I don’t think about it,” Basik explains. “Alright, I got it out. But I’ll go back and look at it – it really makes you look at yourself in a whole different light.

“I love the connection you can make with it. Because you realize, when you put that part of yourself out there, that everybody has that part of themselves.”

Adds Righteous: “It’s being who you are – but with the volume turned way up.”

From “Got Nothing”:

Spittin’ hieroglyphics through my lyrics

Chicken scratch, spittin’ raps in verses

That convert to pyro, hittin every constellation

that could stop a nation

Respect

“We started off making the biggest mistake that you can make when you’re an underground rap group,” explains Knife. “Our first release was a compilation – proving the point that we didn’t really know what we were doing. We just knew that we had a bunch of guys who could rap, we knew a bunch of guys who made beats, and we just kinda threw everything on.”

Union of Sacred Monsers is an entirely different animal. “Removing myself from it, just sitting back and listening to it, I’m like ‘This really sounds like a rap group.’”

Jon Darling, who’s one of Dope Sandwich’s DJs, and the group’s de facto manager, says that when they do out–of–town gigs to promote the new CD, Zone–D, Blue Collar and the others will re–join the crew as their schedules (and new lives) allow. No one ever really leaves Dope Sandwich.

“People have moved away, but we still communicate, they still do a lot of work with us,” he explains. “At first, it was so tight that if we needed T–shirts done, one of our friends would silkscreen them. Or if we needed a CD package – it was so tight knit. We were a community. Everybody was involved in the hip hop community, they were either break dancing, rapping, DJing, or some sort of graffiti art or graphic design. They were doing something.

“Meanwhile, they’re applying for jobs. They get jobs. Ask any of them, their roots are still the hip hop shit they were brought up on in Savannah.”

Not that touring – and/or getting famous – is the ultimate goal.

“As many shows as we’ve done on the East Coast,” Basik says, “I don’t get the feeling from other artists that I do here. We’ve done shows in a couple of bars in New York, and we’ll rhyme on the streets with MCs there, and I still don’t even get that same feeling I do here in Savannah.

“People around here, they’re competing because they love what they do.

“Honestly, the one thing I’ve felt really, really good about these last couple of years is the respect we get from other musicians and other artists around town. Being a hip hop artist in a town full of really sick–ass musicians, and getting that respect from them, means a lot to me personally.”

All three MCs, and Jon Darling, wait tables during the day.

“It would be nice to get to another level where we’re able to perform in other cities, if only for the fact that it would pay bills,” Righteous says.

“At the same time, being here in Savannah has given us the chance to get our shows down pat. People always say ‘When do y’all rehearse?’ Well, we don’t really rehearse, we’ve just been doing it together for so long, we know each other like that.”

Learn more about Dope Sandwich and Union of Sacred Monsters at www.dopesandwich.com, www.dopesandwichproductions.com, www.myspace.com/dopesandwichmusic.