One of the films presently coursing though the nation's art-house circuit is Jodorowsky's Dune, which looks at Chilean writer-director Alejandro Jodorowsky's ill-fated attempt to make a cinematic version of Frank Herbert's novel back in the 1970s. Another current art-house effort is The Dance of Reality, which could easily have been called Jodorowsky's Amarcord and thus provide matching bookend titles.

Like Amarcord, Federico Fellini’s Oscar-winning gem, The Dance of Reality finds its creator mixing fact and fantasy to present an autobiographical look at a childhood seen through a particularly kaleidoscopic filter. Of course, there’s no reason to think that the Fellini flick is what inspired Jodorowsky to set his sights on his own distant past; on the contrary, the eccentric auteur, who’s helmed only seven pictures over the course of 45 years—in terms of quantity, he makes Terrence Malick look like Woody Allen—clearly digs down deep into the recesses of his own mind to come up with his startlingly original visions.

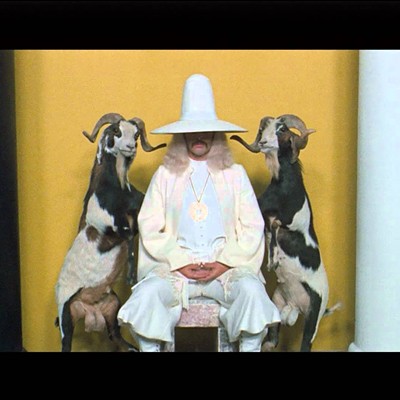

The Dance of Reality is no different: While it may look as streamlined as a Mickey Mouse cartoon when compared to his trippy cult classics El Topo and The Holy Mountain, rest assured that it’s still more innovative and unique than most anything else in theaters in 2014.

This much is based in fact: Alejandro Jodorowsky was born in Tocopilla, a Chilean town whose name means “the devil’s corner.” Certainly, Jodorowky suffered a hellish childhood growing up, as he’s recounted in interviews and based upon the sights seen in this picture. His parents Jaime and Sara were Jewish-Russian immigrants, and his dad devoutly followed the Communist Party. These background details are dutifully related in the movie, but much of the rest proves to be more fanciful, trafficking in the sort of unbelievable, eye-popping imagery and loopy non sequiturs that would have made Luis Bunuel proud.

The plotting also becomes more nebulous, with the filmmaker himself appearing on the scene to provide narration to viewers as well as comfort to his childhood self. This boyish Alejandro (played by Jeremias Herskovits) is a miserable tyke, saddled with a tyrannical father (Brontis Jodorowsky, Alejandro’s real-life son) and a sometimes suffocating, sometimes aloof mother (Pamela Flores) who doesn’t speak normally but instead sings every word that emerges from her mouth. Jaime is determined to mold his sensitive son into a man, so he verbally and physically abuses the lad at every turn. Alejandro doesn’t have it any easier with other kids, as they call him “Pinocchio” and insult his Jewish heritage (in one scene, a group of boys mock his circumcised penis, with one declaring, “Ours look like bananas; his looks like a mushroom!”).

As Alejandro suffers the slings and arrows of family members and fellow denizens, we expect the picture to follow the template of most coming-of-age yarns and show how this young intellectual breaks the shackles of provincial living in order to move away and make his mark on the world. Instead, the picture takes a right-hand turn and makes Jaime, not Alejandro, its central character. Obsessed with assassinating fascistic Chilean president Carlos Ibanez (Bastian Bodenhofer), Jaime leaves his wife and son and sets out on his mission. This narrative about-face turns out to be both a blessing and a curse. Jaime’s odyssey, packed with all manner of suffering, allows him to soften and claim his humanity and sense of decency, and it’s genuinely touching how Alejandro the filmmaker appears to be using his movie as a gesture of forgiveness, absolving his father of all his sins.

Conversely, though, this plotline, which dominates the entire second half of this 130-minute movie, becomes repetitive after a while, using various incidents to hammer home the same point that this man is no more than a paper tiger cut down by the weight of historical upheavals.

But even when one feels that Jodorowsky’s script is rambling (particular in some late sequences involving young Alejandro and his mom), there’s no faulting the one-of-a-kind visuals on display throughout the picture. Often employing bright, splashy colors and finding significant supporting parts for dwarves, hunchbacks and amputees of all stripes—in short, the kinds of people generally kept away from movie cameras but here embraced wholly by Jodorowsky—the filmmaker ensures that The Dance of Reality unequivocally sways to its own rhythms. (Three stars).