THE WORLD feels so vast at times, it’s easy to fade into the background or not to feel seen.

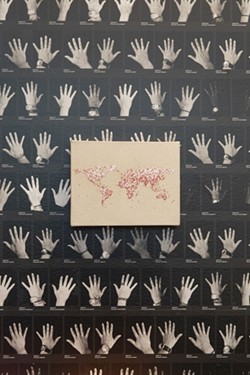

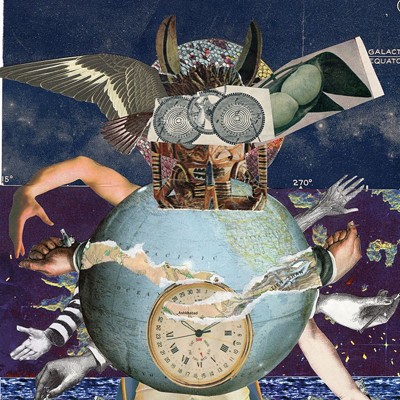

Artist Capucine Gros takes on huge projects of enumerating the presence of individuals to make a statement about our global community.

“The Center is Everywhere,” on view at the SCAD Museum of Art through Aug. 11, presents five of Gros’ ongoing projects that pay an impressive, almost maddening, attention to detail.

The title comes from Nigerian poet Ben Okri.

“It’s a very abstract title, but it really resonates with a lot of her work,” says Ariella Wolens, assistant curator of SCAD Exhibitions and the curator of this exhibition. “[Okri] discusses the history of colonization and how the colonizer has always spoken for the oppressed, but hasn’t always spoken that effectively, and that this sense of egocentric history is really a false notion.”

The French artist graduated from SCAD in 2012 and has been working on the projects on view since that time.

“Each piece really deals with notions of geography and personhood,” says Wolens. “Through each piece, she’s really trying to give visibility to every individual that she encounters to try and get a sense of people that generally don’t have exposure, either through media or literature or culture.”

Take, for instance, “Approximately 199,” which began when Gros wondered how many countries are in the world.

“It seems like a very simple thing to answer, but as it turns out, it’s almost arbitrary and really depends on the political body that’s determining it, and they have very different criteria to establish that,” says Wolens. “The number is in the region of 200. She wanted to keep it with this sense of inaccuracy and vagueness, but also to have space devoted to people who are stateless, who are refugees and who really are not represented by any nation.”

Gros began by drawing the silhouette of each country in a sketchbook, then turning the sketches into prints with an acetate transfer process. If you look closely at each print, the shadow from the other side of the paper is also visible.

“It’s always having a sense of the other within each image,” explains Wolens.

In the exhibition, the prints are arranged by population size, beginning with the Vatican and ending with China. Gros also printed the counties onto shirts and wore a shirt each day for 200 days, again arranged by population size.

“They’re ongoing projects, so they adapt with the politics—some will become obsolete as climate change continues to accelerate,” says Wolens. “They also have this sense of being a Rorschach test, a visible sort of symbol of interpretation. It’s a personal history, too—what are your reference points? How do you read this?”

Another project of Gros’ is “Ten Years.”

“She wanted to determine how many people she engaged with of those she encountered,” says Wolens, “so on her hands, she marked on her left every person she passed or saw, and on her right every person she acknowledged.”

Part of the magic of Gros’ projects is a looming sense of futility. The task of tallying every person you see in a day seems impossible and raises so many questions from the viewer—how could you possibly enumerate every person without missing someone, or counting someone twice?

But the biggest question of those is: why not try? Gros’ enumeration of individuals in this way creates a sense of community and togetherness we don’t often see today. Gros became an artist to take that work on.

“I became an artist because I felt that it was a way to choose everything at once. I was interested in too many different things and different places to pick a single career,” says Gros. “The thirst of ‘exploration of humanity’ and of traveling is precisely the source of my artistic path. I think it’s not easy to keep this freedom. Every artist has to dance around all sorts of borders—the commercial imperatives, the categorization that others will try to put on our practice, geographical injustices—but this is just part of the work.”

Gros throws herself wholly and tirelessly into her practice, juggling multiple projects at once and all for the greater good of destroying those artistic borders. The end result of that devotion is that the projects feel less like work and more like an extension of herself.

“To be perfectly honest, my most lengthy projects were born, in a bit of a beautiful irony, from my time limitations,” says Gros. “Over the years, I’ve accumulated quite a few long-term projects like this, but I do build them slowly and they become so assimilated into my routine that I don’t think of them anymore as work. Once they become an intimate part of my life, I feel ready to pick up a new one.”

That devotion doesn’t translate to a typical view of commercial success, which lends more authenticity.

“This isn’t a practice this is very salable, but she’s fully committed regardless of the commercial availability of her work,” says Wolens. “She just lives it. She decided that she felt like a hypocrite being in the United States and making this work about going against Euro-American centricity, so she packed up and moved to Bucharest.”

“Of course, I hope that outside visitors will get a little consciousness shake from their visit of the exhibition,” says Gros. “Think a little more about parts of the world they maybe didn’t care about before, get a better awareness of their own bias, think a little differently about strangers. And for students, I really hope they’ll leave the show reassured and hopeful—that it’s okay for people not to understand your work right away, that good things take time to mature, that not everything is measured by sales, and that every challenge we face can be turned into an opportunity to make better, more creative work.”