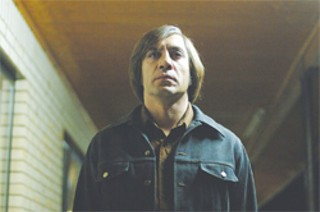

No Country for Old Men ****

The Coen Brothers have always been known for the ease with which they’ve jumped from genre to genre -- screwball comedy with Raising Arizona, gangster saga with Miller’s Crossing, neo-film noir with Blood Simple, etc. -- but with their superb new picture, No Country for Old Men, they seem to be tapping from various wells at once. Certainly, their adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s novel smacks of a contemporary Western through its wide-open settings and signals a crime thriller via its “law and disorder” plotline. But may I add the classification of monster movie to the mix? That might seem like a stretch, but as I watched Javier Bardem’s seemingly unstoppable Anton Chigurh shuffle his way through the picture, killing left and right without remorse, I realized that it’s been a looong time since I’ve seen such an unsettling creature on the screen. Chigurh is just one of the several fascinating characters occupying screen time in a delirious drama that in its finest moments echoes such classics as Psycho, Touch of Evil and Chinatown, not only in its intricate and unpredictable plot structure but also in its look at an immoral world in which chance and fate battle for the upper hand and in which evil is as tangible a presence as sticks and stones. Chigurh, who finds it easier to murder an innocent bystander than to crack a smile, is described by another character as operating by his own set of principles, and only in a topsy-turvy world could a fiend such as this be described as principled -- and, more disturbingly, possibly even deserve the designation. Chigurh spends the film, set in 1980 Texas, on the trail of Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), a cowboy who stumbles upon the aftermath of a drug deal gone wrong in the desert (lots of guns, lots of spilled blood, lots of corpses) and walks away from the scene with a satchel containing $2 million in cash. But a sum that large isn’t about to be written off by the crime bosses, and so here comes Chigurh (working for an outfit independent from the Mexican dealers) to take care of business. The cat-and-mouse chase between Chigurh and Moss is enough to propel any standard narrative, yet tossed into the mix is Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), a weary sheriff who, baffled and deflated by the wickedness that has come to define his country, nevertheless trudges from crime scene to crime scene, hoping to save Moss and stop Chigurh. As we’ve come to expect from a Coens feature, interesting players can be found around every corner -- there’s also Moss’ baby-faced wife (Kelly MacDonald), kept in the dark by a husband whose increasingly frantic behavior threatens to put both of them at risk, and Carson Wells (Woody Harrelson), a jocular bounty hunter who functions as a walking encyclopedia when it comes to detailing Chigurh’s crimes against humanity. All of the performances are exceptional, yet this is clearly Bardem’s picture. So magnetic and full of life in his Oscar-nominated turn in Before Night Falls, he takes the opposite stance here, portraying Chigurh as an emotionally withdrawn individual whose only defining trait (outside of his imaginative choice of weapon) is the whimsical manner in which he occasionally allows a potential victim the opportunity to call a coin toss to decide their fate.Beowulf ***

Director Robert Zemeckis, whose 2004 The Polar Express felt like an animated feature that had been embalmed, again employs the “performance capture” technique (or “digitally enhanced live-action,” per the press notes) with far greater success, overlaying real actors with a cartoon sheen and placing them in the middle of a CGI landscape. In 2D, which is how the film is being shown in most theaters nationally, this runs the risk of looking as soulless as many other CGI works, but in 3D (presented only at select venues), it results in a positively astonishing experience. Tossed coins roll directly toward the camera, spears poke directly out at audience members, and even an animated Angelina Jolie’s, umm, assets seem more pronounced than usual. Based on the ancient poem, a staple of most school curriculums, the script by fantasy author Neil Gaiman and Pulp Fiction co-writer Roger Avary doesn’t always match the movie’s visual splendor (burp and piss scenes show that the makers are clearly hoping to attract the fanboy crowd), but their modifications to the ancient text are more often than not respectful. After the gruesome monster Grendel (voiced, or, more accurately, snarled by Crispin Glover) wreaks havoc on the castle of King Hrothgar (Anthony Hopkins) and his followers, the heroic (and boastful) Beowulf (Ray Winstone) arrives to save the day. Yet he finds himself not only having to confront Grendel but also the misshapen creature’s mother (Jolie), envisioned here as a seductress with the power to lead any noble warrior astray. The biggest criticism has nothing to do with the movie itself but with the morons on the MPAA board. With its flashes of nudity and abundance of gore (for starters, one character gets ripped in two), this clearly deserves an R rating, but perhaps only equating animation with Mickey Mouse and Fred Flintstone, the moral watchdogs handed this a PG-13.

Enchanted *1/2

It’s a nice touch having Julie Andrews serve as (unseen) narrator for the bookend sequences in Walt Disney’s Enchanted. Andrews, of course, played the title nanny in the studio’s Mary Poppins, which contains the famous phrase “practically perfect in every way.” And I can’t think of any better way to describe Amy Adams’ performance as Giselle, the animated damsel who doesn’t long to be a real girl but becomes one anyway. Enchanted begins in the style of the classic Disney toon flicks of yore, with the beautiful Giselle, at one with nature and its furry inhabitants, longing for “true love’s kiss” from the lips of a handsome prince. She gets her wish when she meets Prince Edward, but his scheming stepmother Queen Narissa, not wanting to relinquish the throne, banishes Giselle to a faraway land, which, it turns out, is our own New York City. Now flesh and blood, Giselle turns to a stranger, a buttoned-up divorce lawyer (Patrick Dempsey), to help her survive in this bewildering city; meanwhile, others arrive in the Big Apple in pursuit of Giselle, including Edward (James Marsden) and the evil Queen (Susan Sarandon). Entrusting such a rich premise to the writer of Sandra Bullock’s dreadful thriller Premonition is a dubious tactic, and, indeed, Bill Kelly doesn’t come to exploiting this subject for all it’s worth. But that’s not to say there aren’t moments of genuine inspiration, such as when Giselle calls out to the creatures of NYC for help and instead of the expected rabbits, deer and chipmunks gets rats, roaches and pigeons instead. But what pushes the film over the top is the terrific turn by Adams, who really seems like a Disney heroine come to life (as the preening prince, Marsden also displays fine comic chops). Her performance is every bit as enchanting as one dreams it would be.

August Rush **1/2

The sound of music comes alive in August Rush, a charming family film that pushes the always-welcome message that the arts -- in this case, music -- can inform and enhance our lives, leading us to places we’ve never been and allowing us to establish meaningful contacts with other like-minded people. There’s no denying that the movie, which often plays like Oliver Twist as conceived by the dance troupe Stomp, is sweet and heartfelt and full of passion. But there’s also no denying that it’s clunky, haphazard and not especially well-written or efficiently directed. If you’ve seen the trailer, which seems to go out of its way to reveal every important scene (even the climax), then you already know that August Rush is the story of Evan Taylor (Freddie Highmore), an orphan whose parents -- a cellist (Keri Russell) and a guitarist (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) -- don’t even know he exists (Mom was told by her controlling father that he died during childbirth). But young Evan is determined to find his parents, and he believes that through music they can be reunited; i.e. that they’ll be able to magically hear him and locate him. Thus, he escapes from the orphanage, making his way to New York City and falling in with a band of street kids working for a Fagin-like musician-promoter (Robin Williams). That Williams’ character turns out to be a controlling bully is one of the picture’s few surprises; everything else falls neatly into place, thanks to a script that needs about 128 coincidences to retain its forward momentum. The best way to enjoy August Rush, then, is to accept it completely as a fantasy; applying any sense of realism to any of its scenes might cause one’s head to explode.

Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead ***

If I’m still around at the age of 83, I doubt I’ll even be able to successfully navigate the remote control. Yet here’s the great veteran director Sidney Lumet (Twelve Angry Men, Dog Day Afternoon, The Verdict, and on and on and on), who, just two years after winning a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Academy, has made an impressive picture that’s earning him his best reviews in ages. And for at least three-quarters of the way, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead deserves those stellar notices, as it shapes up to emerge as one of the best films of the year. But like a long-distance runner who miscalculates his own endurance level, it falters at the very end, with a two-pronged wrap-up that disappoints with both barrels. \Philip Seymour Hoffman heads the powerhouse cast as Andy, who, sensing that money might be the way to save his faltering marriage (to Marisa Tomei’s Gina), talks his weak-willed younger brother Hank (Ethan Hawke, never better) into taking part in the the robbery of a jewelry store -- the one owned by their parents (Albert Finney and Rosemary Harris). Andy envisions it as one of those victimless crimes -- use a toy gun, rob the place when there are no customers, the owners recoup their losses via insurance, etc. -- but we all know what happens to the best-laid plans. At first glance, Before the Devil is one of those post-Memento neo-noirs that believes it’s necessary to tell its story in a fragmented style that skips between past and present. But as played out, this technique isn’t merely for show but as an immediate way to pinpoint how each dire consequence is the result of several major and minor decisions.