When a wide-eyed Roberto Carlos Lange stepped onto the SCAD campus in 1999, he sure didn’t know where his college journey was about to take him. With an interest in computer art and animation, Lange didn’t consider himself a musician, but he soon found himself experimenting with sound-making.

17 years later, his project, Helado Negro, is an indie sensation. Lange is signed to Sufjan Stevens’ Asthmatic Kitty Records label and Helado Negro is stunning audiences with a unique blend of visual, audio, and performance art.

The son of Ecuadorian immigrants, Lange grew up in the Latin American melting pot of South Florida. The tropical vibes, sunny sensations, and dancehall flavors of his childhood shine throughout his diverse catalog. The innovative Lange wields a computer and his voice to craft warm, electro-pop tunes that evoke a kind of wistful nostalgia and hypnotic sincerity.

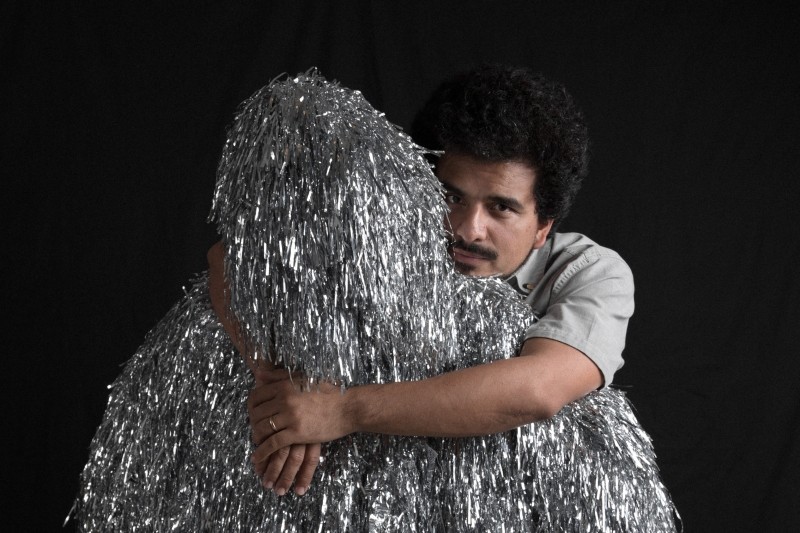

Talented in a variety of artistic disciplines, Lange’s live show is a multisensory sensation. As he croons, alternating between Spanish in English, “tinsel mammals”—dancers clad in metallic fringe, resembling something that might happen if performance artist Nick Cave and director Hayao Miyazaki were to collaborate—move and pulse around him like gossamer dream forms, bringing the stage to life in the most surreal, magical manner.

This summer, Lange released the excellent single “Young, Latin, & Proud.” It’s a soft tune with a gentle dance beat, meant to be sung in unison, crooned to children, belted boldly, confidently and defiantly. Stunningly beautiful in its simplicity, it was a hit, and was named one of the best Latin songs of 2015 on many year-end lists.

We chatted with Lange about his unique collaborations (he’s worked with everyone from Devendra Banhart to Sufjan Stevens to Mikael Jorgensen of Wilco to world-class orchestras), the Savannah DIY scene in the late ‘90s, and pushing a stage show from a one-man production to a dazzling spectacle for the eyes and ears.

You’re a SCAD alum. What did you study while you were there? How did it impact your work?

I was in Computer Art—at the time, that’s what it was called—it was mostly visual work. And I also studied Sound Design. It wasn’t developed as a major; it was mainly focused on fine art-based work, more like installation work, more experimentation with sound.

It was very fun at the time. I have fond memories of being in Savannah. The whole lot of us, we were throwing house parties and shows, weird functions with as much experimentation as possible with sound and performance.

That’s awesome. What was the music scene like then?

For me, it felt like there were a lot of people who were way more into just having music happen as much as possible. There were a lot of people having house shows downtown, and it was a range of music, and it was just people doing improvised, weird music, a lot of improvised electronic music.

There were some staples you associate with Savannah: the indie music scene, hardcore, heavier rock. There was a lot of turntables and a lot of hip-hop at the time. It was always a huge mix of things and people interested in doing something. That’s my memory of it—it could be romanticizing something from my youth, but it was definitely influential at the time.

That’s really interesting to hear. The house show scene is really back in full swing here.

Yeah, no one really got busted, no cops came. At the end of the day, nothing was terrible—nothing I knew of was happening. It was multiple events we put together; we’d be participating, focused on music and sharing and having fun and performing.

Were you playing music before college?

No, it all developed there. By the time I got to SCAD, I was really interested in sound and music, and I had been exposed to a lot of experimental music, a lot of electronic. It was 1999, I think, when I got there, and I got a piece of equipment, a sampler sequencer called MPC. That was what I learned how to make music on while I was in Savannah, essentially. I learned the process of being inspired by the visual experience there, learning through art school, and also the influence I had from taking classes, like the sound classes. Like I said, a lot of professors at time really focused on sharing things that were a little bit more esoteric, outside commercial sound, more in the field of experimentation. They helped anyone who was really young and wanted to know about more.

The department is so different now. So much of it focuses on sound for film.

I think as I left it was transitioning. And it think there’s an accountability and accessibility to it. I think as teacher at school, you want to create a place where, if you are taking money—that amount of money!—a lot of people have an expectation of that money. I think the easiest way is to get them exact skills, things that are very, very practical. When things become abstract and experimental, the world is kind of harder, and I understand that, and I was faced with that getting out of school like, ‘Where do I land?’ And luckily I’ve been able to develop what I am and what I do with my work to do what I’m doing now.

When did you begin incorporating a visual aspect into your music?

It’s always been there. I remember one of first films I saw at SCAD that really influenced me was by an animator Norman McLaren, the film was called Neighbours. I got more into his work and just really was intrigued by it, by the color and the light, the real playfulness of the process. I think his work was a big influence on what I'm interested in and what I'm doing currently in terms of light movement. It's always been that, it's just everything moves at a different speed, even if side-by-side, the music evolves and moves in different ways, and what I've been doing visually has been trying to keep the duality.

As your show has developed visually and you've added your tinsel mammals, do you feel like your stage presence as an individual has changed?

The tinsel mammals came as a response to my stage presence. I compose music with computers electronically. I think, at this point in the world, it may come across as old hat—meaning everyone has a computer and everyone composes in same way—and this is the only way I've been doing it, but it's pretty much the way I've composed music since 1999, and so as you're performing it, that's a huge leap.

Prior to [Helado Negro] I had another project that was touring a lot in Japan. It was more experimental/instrumental music, and something I learned from that was this separation. People got lost in the music, and there was a certain crowd that was out at a specific time that was listening to the music.

As I shifted into singing more, that changed a lot. I think when you’re singing and you’re doing anything with your voice and performance, the audience changes their perspective. They’re not just getting swallowed up by the music. The voice sometimes requires a different kind of attention, and people really change the way they’re looking at you: they’re not just looking at you, you’re becoming a part of the performance a bit more when you’re doing that. When I began to sing and perform, my body started moving certain ways. There’s an intuitive quality and gradual evolution of what all was happening.

Since 2009 to 2013, I was dancing in a specific way, and then I decided to create some kind of reflection of that movement and dance, and that’s when the costumes came around. The idea was to try to have something else onstage in response to that.

Had you choreographed anything before? Did you have experience directing?

I didn’t have any exposure to that at all. I had a specific show in Mexico City in 2014, and I never really liked the way the stage looked at festivals in the day. You’re looking at gear made for clubs in nighttime, and and it’s five in the evening.

My solution was to find something to reflect light that was also moveable and also modular in the sense of they can change shapes without heavy manipulation, you know? I thought of these costumes, and my wife suggested working with tinsel, and so it was definitely a collaboration in that aspect.

I got to Mexico and had to figure out how to make the suits there. I was like, ‘Wow, I have two days before the show and I have to figure out movements and see what’s good and what’s not, and I have zero experience in choreography!’ Now I have a little bit more, but that first year, 2014, I toured 60-70 shows and got a list of volunteers—people would write and say they were interested in doing it. I designed a specific amount of movements that were really easy to learn and would come across as if it was completely choreographed, or touring dancers, because no one would know. There’s an anonymity to the costume. This past year I’ve been working with professional dancers, and it’s been really eye-opening. I’ve worked with a handful of great companies and dancers who really contributed in terms of collaboration.

I found it really parallel to music and working with musicians: you can ask to work together, and there’s an influence there.

Yeah, you’ve collaborated with a huge variety of musicians and orchestras, even.

Last year I did an 18-piece ensemble show with St. Paul Chamber Orchestra Liquid Music Series; I had a great opportunity to bring together a lot of people I’d collaborated with in the past and bring together in a big group. Lætitia Sadie from Stereolab was a special guest and sang a few songs.

Whoa!

Yeah! The wildest thing about that was I had an opportunity to understand the science behind my music, in terms of notation. I never went to music school—the way I learned to make music was finding sounds and assembling them. It was never in this formal way.

What I learned through this formal process was the science of notation, how everything’s very broken down into numbers. So it was a way for me to look at my music and see how it transitions to a large group of people. If anything, it made me uncomfortable! You see your own patterns, you see the math behind it, the math in your work.

You’ve worked with museums in the past in addition to “traditional” music venues. How do you adapt to the different environments?

I do work with a lot of museums. It’s a good partnership...specifically bringing the tinsel mammals and working with a couple of dancers.

Performing in front of people is such an exciting thing about being a touring musician, and it’s the hardest thing, because as much as you perform something, there are always people who haven’t seen it. So there’s always the pressure to make something new. There’s new aspects to what I’m going to be doing—I’m performing new music, there are newer movements, but there’s also deeper connotations on how the show can work in the space they provide.

There’s a lot of one-man band show aspects of what I do: I travel by myself, there’s a lot of modular lighting ideas that I bring that I design myself with the suits, and it just comes out of something of feeling responsible to transform an environment everywhere I go, put that energy out there, and have people know this was a special night for me. And I hope it will be for them.