THESE days, James Lough is a man of few words.

In 2015, the writer and SCAD professor co-edited Short Flights: Thirty-Two Modern Writers Share Aphorisms of Insight, a collection of quick, pithy observations from an array of literary luminaries.

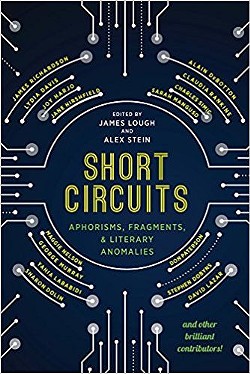

Three years later, he and co-editor Alex Stein continue to explore brief verse with Short Circuits: Aphorisms, Fragments, and Literary Anomalies, an anthology that returns to aphorism and includes other short-form writing and poetry from voices around the world.

On April 26, Lough will celebrate the book’s release via Schaffner Press with a reading at the SCAD Museum of Art.

“As much as I love aphorisms, there are so many other really short genres that people are working in right now,” he says.

“There are super-short poems, micro-fictions, mini-essays. The stuff they call ‘flash fiction ‘today is good work, but far too long—a page or two is Moby Dick compared to what we’re doing. We wanted to go short, short, short and include as many little genres as possible.”

After the warm reception for Short Flights, Lough was struck by how many writers were opting to craft powerful literary works on small scales.

“Frankly, we had no idea how many people were writing aphorisms after [Short Flights],” he says. “Writers connected us with other writers, and that kept expanding.”

Lough also dove into the Internet to find new contributors, spending a lot of time on Twitter. There, he found William Pannapacker, the voice behind @WernerTwertzog, and Patrick Carr and Clayton Lamar, the collaborators responsible for @dogsdoingthings.

Through their work, canines wax poetic on pop culture, history, and literature; in Pannapacker’s tweets, he adopts the tone of famed director Werner Herzog.

“What I wanted was younger writers,” Lough says. “There’s a little bit of dispute in the community as to what counts as aphorism and what has to be a joke. I think I’d rather just ask, is it well done? Does it work? Does it have a purpose? Does it have a twist? Some contributors are comedians more than writers.”

Take, for example, Twitter-famous Charlene DeGuzman and Mike Ginn, who pen excruciatingly funny one-liners. Others use limited space to discuss issues that are far bigger than their word count.

“I’m open to any kind of tone,” Lough says. “Some are soft, others are kind of dark. The short memoir pieces by Claudia Rankine are really explorations of what we call ‘microaggressions’—little examples of unconscious racism that a lot of people might not be aware of in themselves, but the people who are discriminated against are. She plays it out in these short pieces that are extremely powerful and illustrative to point out to readers who might be aware of how they make people feel. Some are serious, some are absurdist, some are very light. They’re all welcome.”

While shortform literature may seem like a product of the digital age, it is anything but. The practice is found in countless cultures and was particularly popular among monastics in the Middle Ages.

“It’s a very old genre,” Lough points out. “In the days before Christ, not a lot of people could read, so even the people who could read maybe couldn’t read too much without being challenged. One to two sentences would keep them thinking about it for the rest of their life! That’s how these things started historically, and every culture has produced a super-short work. It wasn’t really until the 1800s in Europe, France, Germany, and England that aphorisms as we know them came into being, where you were expected to be witty and make someone feel a little bit scandalized. Oscar Wilde was the champion for startling and even subversive little quips.”

Even Zen practitioners explored the art in order to alter their thinking patterns. Scientists have studied how short writing can alter one’s mental state—the surprise that lies in a cleverly-phrased aphorism actually does rewire a human’s neurological pathways.

Those paths inspired the book’s title and inspired the jacket design, created by SCAD alumna and book designer Jordan Wannemacher.

“I love hearing about the role of surprise on the brain,” Lough says.

“It’s literally the surprise that comes from reading something. In longer works, that surprise can happen with a plot twist. In shorter works, it has to happen with a sentence twist, one little surprise. One scientist calls it ‘miniature enlightenments.’ He is of the theory that, if you have enough of these enlightenments, they lead to more and more and approach the ‘grand satori’ that is talked about in Zen. It really can change people’s brains for the better.”

For his Savannah reading, Lough is joined by contributors Zara Bell and Eric Nelson, who will share their own literary anomalies with the audience.

“Expect the unexpected,” says Lough.

“The purpose of this kind of stuff is that we like to surprise people. Look forward to little-e enlightenment—and maybe even big-E Enlightenment.”