Flannery O'Connor might have agreed with the oft-quoted notion that art should "disturb the comfortable and comfort the disturbed." Or maybe she would argue that art should unnerve everybody, regardless of station.

After all, O'Connor's writing is full of freaks, misfits and other characters challenged by violence and ignorance, with hardly a sympathetic one in the bunch. Her work provided stark observations of ordinary lives and small minds; not much comfort to anyone seeking easy answers and blind faith.

She did, however, possess a wry sense of humor, and so helped define the warped literary view of humanity construed as distinctly Southern.

"Anything that comes out of the South is going to be called grotesque by the northern reader, unless it is grotesque, in which case it is going to be called realistic," she once retorted in response to criticism regarding the dark nature of her stories.

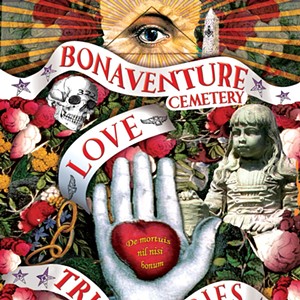

O'Connor wrote what she saw, declaring that "the basis of art is truth, both in matter and in mode," and would surely appreciate the work of several dozen visual artists charged with interpreting her work for the canvas. Diving deep into O'Connor's Complete Stories for inspiration, these artists explore themes of racism, rural life, spirituality, unexpected beauty and more in "Southern Discomfort 2," an art exhibit on display all this week at ThincSavannah. Preview hours are 9am-5pm, Mon.-Fri. with a final reception and silent auction on Friday evening, Jan. 31.

Even though she once described herself as a "pigeon-toed child with a receding chin and a you-leave-me-alone-or-I'll-bite-you complex," Savannah loves its Flannery. She was born here and lived in a modest three-story rowhouse on Lafayette Square until 1950. She moved to Milledgeville in her 20s to write, raise peacocks and tend to her failing health.

Though she died of lupus there at just 39, the Flannery O'Connor Childhood Home remains a revered historic institution (Pat Conroy called it "one of the temples of world literature" in 2010) and the city still claims an intimate connection with the author herself.

"I think Savannah has a pretty playful relationship with Flannery," considers Beth Howells, AASU English professor and secretary of Friends of Flannery, the non-profit dedicated to caring for the house museum.

"I think our town respects that she is a quirky character, not easily pegged, full of dichotomies: she doesn't conform to easy definitions of religious, feminist, intellectual, writer, anything really. I think there is something about that refusal to conform that makes her admirable around here."

Two years ago, Howells and fellow Friends of Flannery board member Bill Dawers invited a group of artists—some local, some far-flung—to submit works inspired by the gothic queen of Southern literature as a fundraiser. The project was a tremendous success, showing paintings at the 1704Lincoln gallery space from 45 artists, many of whom donated the entire sum raised from the silent auction back to the foundation.

"Southern Discomfort" has been revived once again with an astounding line-up of artists, including previous contributors Marcus Kenney, Christine Sajecki, Carmela Aliffi and Todd Schroeder. All paintings will be up for auction at Friday's reception.

Painter Tim Wirth is a first-time Southern Discomfort contributor and first heard of O'Connor as an MFA candidate at SCAD (a couple of his large works, including Statue of Something Important, are currently hanging in shopSCAD.) But he admits he didn't sit down with any of her work until back in his native Iowa.

"I read A Good Man Is Hard to Find and it gave me a chill that I couldn't shake," he says of O'Connor's famously violent tale.

He submitted three small works for the exhibit and auction, deriving inspiration from O'Connor's introspective memoir A Prayer Journal, written during the time she spent at the University of Iowa Writer's Workshop.

"I found out she spent time studying in Iowa, not far from where I once lived," says Wirth, who still lives and works in Iowa.

"I liked that geographical connection and it felt as though she was a bird of prey whose migration path was similar to my own, just in an opposite pattern."

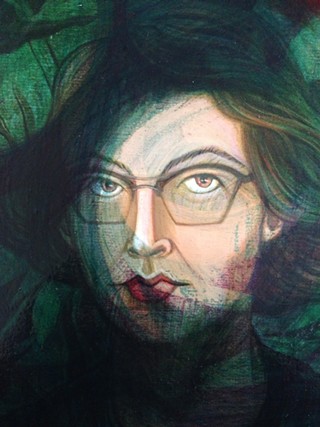

Even for those returning to the well, O'Connor provides endless fascination. Katherine Sandoz mused on the short story "Good Country People" for "Finding Joy," the layered abstract she presented in 2012, but this time around, she found revelation in the visage of the artist herself. Far from a simple portrait, "Finding Flannery" depicts the author in a one-eyed squint, forever suspicious of humanity's motives.

Sandoz uses her subject's signature peacock tones to relay O'Connor's darker sentiments as well as project the way her writing has been bruised and battered over time by constant examination. Sandoz had no problem revisiting O'Connor for the show, explaining that it was a question of tackling the same problem from a different angle.

"Everyone in Savannah is always rediscovering Flannery," she says. "Her writing is so dense, her personality so dense. She also talks about writing to discover, and I think visual artists are the same—they make to know their subjects or material a little better each time."

O'Connor likely understood the relationship between writing and art: She was a prolific cartoonist throughout high school and college and a book of her cartoons and sketches was published in 2012, giving Flanneryheads more material to ponder.

"People don't just interpret but respond to her," muses Helen Borrello, another English professor serving in her third year as FOF president. "There is something about her that attracts vibrant, interesting people from all over: The Catholic community, literary circles, and the visual arts."

Borrello believes that it is the writer's willingness towards nonconformity, to tackle the "grotesque" elements of society at a time when such ideas went outspoken (especially by women!) that makes her so endlessly compelling. Those same problems of race, violence and spiritual confusion still abound, and readers and artists continue to turn to Flannery O'Connor not for comfort, but perhaps for communion.

O'Connor offered some interpretations in her letters and later writings, but Borello acknowledges that her work "raises more questions than it answers. She leaves us in a perplexed state."

She laughs when it's suggested that the Catholic O'Connor could be referred to as "the patron saint of Southern freaks."

"I think she would have smiled at that."