In 1970, Georgia’s governor Lester Maddox had a plan for the barrier islands that comprise our coast.

With the development of I-95 on his mind, Maddox wanted to build a state highway through the barrier islands, which would involve surface mining and dredging for phosphate over 70,000 acres of marshland.

However, as anyone familiar with the process knows, surface mining causes disruption to the landscape, notably soil erosion and water pollution.

Maddox first took the proposal to Wassaw Island, hoping they’d be excited about the idea. Instead, they immediately preserved the island through the Nature Conservancy of Georgia to avoid being developed.

What happened next was nothing short of a major feat. A wide swath of citizens—from scientists to business leaders and everyone in between—came together to call for the protection of Georgia’s coastline.

The Coastal Marshlands Protection Act, passed in 1970, rules that marshes are not technically land and cannot be developed as such, protecting Georgia’s unique coastline.

This March is the 50th anniversary of the act’s passage, but the Ossabaw Island Foundation will celebrate it on Thursday in conjunction with its annual birthday celebration for its beloved matriarch, Sandy Torrey West.

West’s family was the last to live on Ossabaw Island before preserving it in 1978, just a few years after she joined in the fight for the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act.

This year, West turns 107 years old, and her birthday celebration moves to the Armstrong Center for the first time. There’s an off chance West may be able to grace the party with her presence, but either way, the Ossabaw Sound Barbershop Quartet will sing birthday songs and birthday cake will be served in honor of West.

The birthday party doubles as Ossabaw’s annual meeting, and this year, the keynote speaker is Dr. Chris Manganiello, Water Policy Director of the Chattahoochee Riverkeeper and a contributing author to “Coastal Nature, Coastal Culture: Environmental Histories of the Georgia Coast,” published in 2018 by UGA Press.

Manganiello was asked to contribute to the project by Ossabaw’s Paul M. Pressly after his collaborator Mark Finlay passed away. He was glad to pick up where Finlay had left off, as he’d been interested in the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act for some time.

“I tend to have this belief that if we think there’s going to be a problem in the future, why not create some sort of proactive policy or piece of legislation to make sure we don’t end up with a problem?” says Manganiello.

During a conversation with a friend about preventative proactive legislation in Georgia’s history, Manganiello brought up the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act, much to his friend’s dismay.

“He was like, ‘Oh, absolutely not. That wasn’t a proactive piece of legislation—that was like a clear and present danger,’” recalls Manganiello.

What made the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act so unique was the passion of the people who came together to make it happen.

“The combination of people who came together for the act wasn’t all environmentalists,” points out DuBose. “It ended up being the developers in the business community. Everybody kind of woke up and realized this marsh is very important to us as a community, as a whole. We all need to lock arms and save it.”

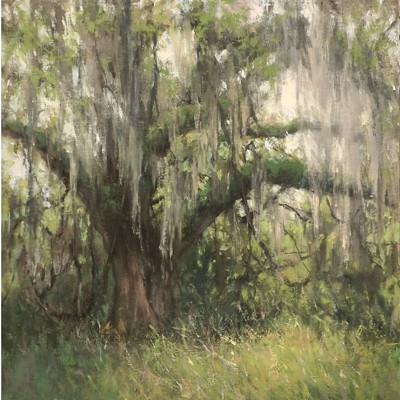

Georgia’s coastline is important because it is unique. As DuBose explains, the Georgia coast holds a third of the salt marsh on the Eastern seaboard. Ossabaw Island itself is 26,000 acres, with only 11,000 acres of that land able to walk or drive on, so the island likely holds much of that marshland.

“The sheer volume and acreage of marshland in Georgia is unique. There’s just no other way to say it,” says Manganiello. “And to the degree that everybody understood that in the late 1960s and 1970s, I’m not entirely convinced they did. Maybe they did. I think a lot of people were just enamored by it because it was fantastic as a resource, and that was enough to motivate them to say, ‘I like what I see, let’s hold on to it.’”

West has always been an avid advocate for Georgia’s coastline. She created a program, Genesis, for college-age kids to learn more about preservation.

“She infused a worry in her participants,” shares DuBose. “When they did their 40th anniversary, we interviewed these guys, and they were like, ‘We felt as personally responsible to make sure that Ossabaw Island was preserved.”

That spirit of conservation, even in the Deep South, is of particular interest to Manganiello.

“What I really wanted to do with this story was to say that sensibility of that environmental ethic was present in the American South in the 1960s,” explains Manganiello. “Environmentalism wasn’t just something that was taking place in New York and California, but it was very present in the state of Georgia, and for good reason.”

Manganiello points out that there’s always been a perception that the South is backwards, but in terms of environmental activism, the region was running parallel to the rest of the country.

“When you think about environmental activism, you probably think of John Muir or David Brower; both come out of this Sierra Club narrative of the American West,” says Manganiello. “But when you take a look at someone like Eugene Odom, who becomes this very popular voice for the emerging science of ecology, he is a Georgian through and through and becomes this national voice for good science and its application.”

Today, concerns about Georgia’s coast are relevant again with proposals for offshore drilling on the table. Fortunately, Rep. Buddy Carter has formally opposed it, but that’s in large part to vocal citizen opposition, much like the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act half a century ago.

“I’d say maybe the closest analog we have might be the general sentiment that opposes offshore oil and gas exploration and drilling,” says Manganiello. “There’s widespread rejection of those activities taking place. People on the coast got their legislators to support a resolution to not support this stuff, and that’s because everyday people made enough noise and there were legislators that were empathetic.”